Why so many marathon records are broken in Berlin

- Published

Kenyan runner Dennis Kimetto set a new world record for the men's marathon in Berlin on Sunday. It's the fifth time the record has been broken in eight years and each time it has happened on the same course - so what makes Berlin special?

The Berlin Marathon started out as a humble affair in 1974 with a mere 284 athletes running through the nearby woods. In 1981 it moved to the city's streets and nowadays attracts more than 70,000 runners every year.

On Sunday it maintained its place in the record books when Dennis Kimetto covered the 26.22 mile (42.2km) course in two hours two minutes and 57 seconds, breaking the previous mark by 26 seconds.

The director, Mark Milde took over from his father, the founder, in 2003. He says there are a few key factors that make it an ideal race for breaking records.

One is that "Berlin is a flat course with few corners". It starts at 38m above sea level, never gets higher than 53m or lower than 37m.

In comparison, London undulates more, twists and turns more frequently, plus runners often face a head wind when running along the River Thames past Embankment. And Boston's finish line is so much lower than its start that it is ineligible for world record attempts.

Also, competitors in Berlin "run on asphalt and compared to concrete this seems to be helpful. We hear from runners that they have less problems with their joints," says Milde.

"And in late September we have running conditions that are close to ideal. There is not much wind and the temperatures are in the range of 12C to 18C."

In fact the average temperature for late September when the marathon is run is 15C - which falls inside the 10C to 16C window that experts agree is the optimum temperature for a fast race.

The good weather and the flat course have blessed Berlin since 1981 but the spate of world records being broken at this event only started in 2007, so what's changed in recent years?

It's widely accepted that we are in something of a golden age of marathon runners with the likes of Ethiopia's Haile Gebrselassie, Kenya's Wilson Kipsang and the current record holder 30-year-old Dennis Kimetto.

Marathon organisers, with the exception of London, can't afford to pay the massive appearance fees to attract all the top stars. But if you want to break a marathon world record you don't actually want all the best runners in one race says Ross Tucker, an exercise physiologist at the Sports Science Institute of South Africa.

"They get to halfway on course for a world record but now suddenly it becomes a tactical battle because no-one wants to sacrifice themselves to pull four other potential world record breakers towards the line.

"The optimum set up to break a world record is to have one or two guys who are committed to going for the world record, who are willing to work together and you just set the race up around those two. London pays for its own strengths sometimes with slower times."

Two top stars raced in Berlin this year - Kimetto and compatriot Emmanuel Mutai helped each other maintain a world record pace until Kimetto broke away three miles from the finish.

Kimetto became the first man to run a marathon in under two hours and three minutes and this has led to renewed speculation about when, not if, we will see the magical two-hour barrier broken.

Kimetto seems to have the world at his feet. In 2008 he was a subsistence farmer in Eldoret, Kenya running four miles a day. A chance encounter with Geoffrey Mutai, a winner of the Berlin, Boston and New York marathons resulted in Kimetto going to train with Mutai and he ran his first competitive race in 2011.

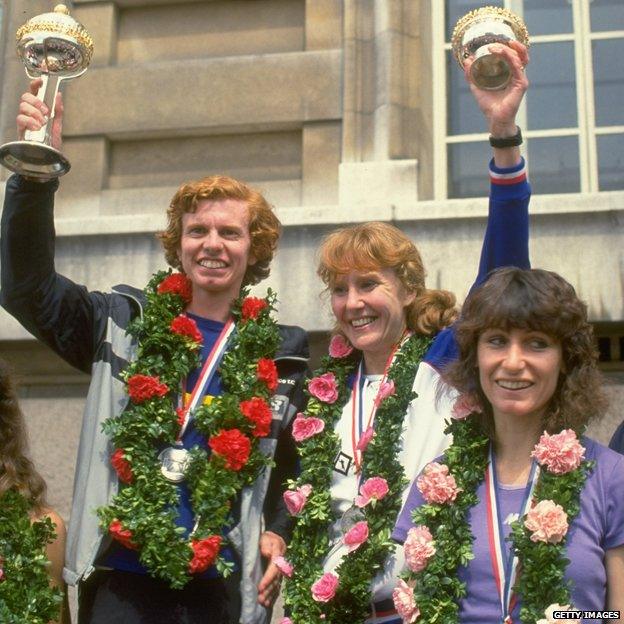

The man who won the London Marathon in 1982, Hugh Jones, isn't surprised at the increasingly competitive nature of these races.

Jones ran a respectable, but now seemingly pedestrian, 2:09:24 but says that an increase in the appearance fees, prize money and the general profile of marathon runners has changed things dramatically in the past decade or so.

"In Kenya and Ethiopia certainly it's seen as a career. You would never have thought that in the days of Abebe Bikila and Kip Keino, and now it is. Athletes are almost a different class of people in East Africa and people aspire to that. Any kid running to and from school sees that, latches on to a training group and climbs the ladder," he says.

There are serious amounts of money on offer too. Kimetto won 130,000 euros ($164,000, £102,000) for his efforts last weekend and the winner of a two-year competition called the World Marathon Majors will get $500,000 (£313,000).

But despite the prize money and the removal of political and economic barriers that stopped previous generations of African runners from competing around the globe, Ross Tucker thinks it will take a long time for someone to go under two hours.

"In the midst of all these records falling, it would be foolish to say that we won't see a two-hour marathon because you'll be shown up within a decade, however I think that what will happen is these 20 to 30 second improvements that we've seen will slow down and become 10 to 15 second improvements.

"If it continues as it has in the last five years, we would see a sub two-hour marathon in 15 to 20 years from now but I don't expect that to happen - I think it will take double that, if at all."

Listen to More or Less on BBC Radio 4 and the World Service, or download the free podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.