US mid-terms: Five things to know

- Published

An introduction to the 2014 US mid-term election through the eyes of "you", a hypothetical senator running for re-election. (Video by David Botti)

The mid-term elections in the US are one week away. Unlike the presidential vote, with one clear winner, these polls are a bit more complicated. So what are the key points to remember?

1. It's all about the Senate

It is very unlikely that the House of Representatives, the lower house which has a Republican majority, will be won by the Democrats. "With a few historical exceptions the party in the White House loses support during mid-terms," says Shaun Bowler, political scientist at the University of California, Riverside.

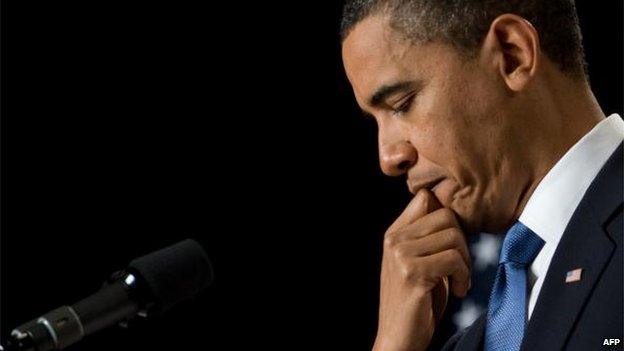

The party of the president has only gained ground in three out of 38 mid-term elections and with President Barack Obama's approval ratings pretty low, there's nothing to suggest this election will buck the trend.

So all the attention is on the Senate, where Republicans need to win just six seats to gain control. This would mean the president would have lost control of both houses since he came to office - handing the Republicans more legislative powers, but retaining his power of veto over bills.

2. Only the hardcore vote

Turnout is generally much lower in mid-terms and it's usually the committed voters that make it to the polling booth.

This time, turnout will be lower than 2006 and 2010 when the Iraq War and the president's healthcare overhaul were galvanising issues, says Frank Newport, editor-in-chief at Gallup. There's no such clarion call this time, and it's a split Congress, which makes it harder for voters to know who to blame.

"In 2010 they could get mad at the Democrats because they controlled both Senate and House. It's a more confusing situation now."

A lower turnout would favour Republicans, who are always more likely to vote in mid-terms than Democrats. Republicans tend to be older and better educated, says Newport, while Democrats are more loosely attached to the system, with a lower registration rate.

"So everything else being equal, Republicans will have a turnout advantage."

3. There's no stand-out issue this time - except Obama

Mid-term elections are nearly always referenda on the incumbent president and this one is certainly no exception, says elections analyst Charlie Cook. And very few Democrats in competitive races are willing to appear with him or, in one case, even admit that she voted for him.

"To the extent that Americans vote on other things, it is the economy, and people don't feel that great about it," he says.

"It's growing, but in low gear. Real median family incomes haven't gone up since 2000, and Americans for the first time in history doubt that their children and grandchildren will have the same opportunities that they had."

Latino voters are disillusioned that Obama has not been able to do more on immigration, and many voters put the dysfunction of government high on the list.

Only 14% of voters approve of the job Congress is doing. Many want to fix how the government operates. But paradoxically, 90% of incumbents get re-elected, so while people hate the institution they are usually happy with the individuals who represent them.

Local factors always play a part in mid-terms too, so abortion restrictions have dominated the race in Colorado and in Louisiana, coastal erosion is an issue. But Republicans nationally want to make it all about the president.

4. It could help shape the big race in 2016

Marco Rubio, Rand Paul and Chris Christie could be part of a wide 2016 field

It's a different electorate in a mid-term election from a presidential one, but there are ways 2014 could influence 2016.

If the Republicans have a feel-good win in a week's time, then the presidential nomination process in their party could become more complicated and divisive, says Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Larry Sabato's Crystal Ball, external. That's because there will be much more incentive to run and the prize of being the Republican candidate will feel more valuable.

"And if Obama's approval numbers look like they do today or worst it will feel like a drag on Democratic candidates."

The working of a familiar electoral cycle - a backlash against the White House - could be over-interpreted as a repudiation of the president, says Bowler. But it will be interesting to see how the Republicans do in winning over non-white voters, because they will be key to their 2016 prospects.

5. The family connections

John F Kennedy (right) with father Joe and brother Joe Jr in the UK in 1938

There's nothing new about dynasties in American politics - you only have to think of the families Adams (two presidents), Roosevelt (two presidents), Kennedy (one president, two more senators) and Bush (two presidents, one governor). Dynasties bring with them personal wealth and name identification. But in these 2014 elections, the phenomenon is all the more prevalent.

The grandson of former president George HW Bush, George P Bush, is running for land commissioner in Texas. And in Georgia, Jason Carter, the grandson of former president Jimmy Carter is running for governor. Other names have glittering political pedigrees in certain states - Udall in Colorado, Landrieu in Louisiana and Pryor in Arkansas.

Then you have Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush standing by to possibly run in 2016.

"Ideally, American politics isn't meant to work this way," says Kondik. "Our country was founded on the idea that we weren't to have an aristocracy. But dynasties are a big deal in American politics. We might not like it but it's inescapable."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.