How the battle against IS is being fought online

- Published

- comments

The battle against Islamic State (IS) militants has been fought in part on social networks, and has raised the question - how best to counter the message being spread by jihadists?

Last weekend, amid the murder of Alan Henning, there was a glimmer of hope.

Between Friday and Saturday night, for once, the online propaganda campaign from IS felt drowned out.

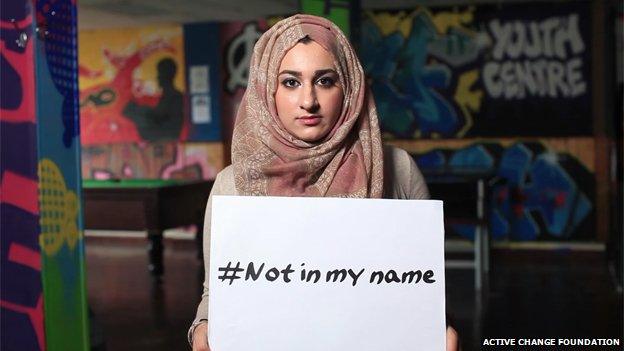

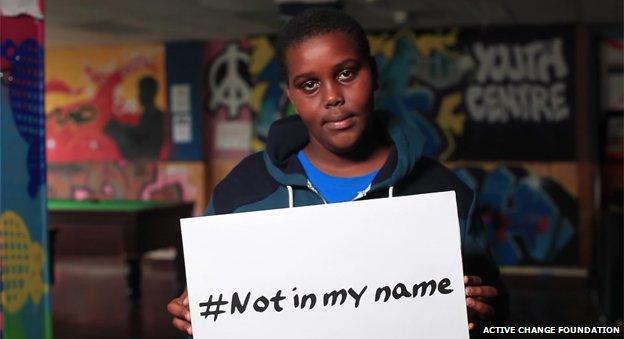

The hashtag #notinmyname swarmed around the net in the hours after reports of Mr Henning's death, driven by Western Muslims who are sickened, heart-broken and furious at how their faith has been hijacked.

Analysis by BBC News shows that over the course of Friday evening the hashtag reached an audience equivalent to those sitting down to watch the main news bulletins.

The hashtag was the brainchild of the Active Change Foundation, an organisation dedicated to fighting extremism.

Hanif Qadir of ACF said he and the young people at the organisation came up with the campaign because the broad mass of ordinary Muslim voices couldn't be heard. They wanted to take back online space occupied by IS.

"It's a simple message," he says. "It's Muslims [and] non-Muslims saying no way, not in the name of Islam, and not in the name of any faith or humanity, It's a very very powerful message and very simple."

Aid worker Alan Henning was murdered last week

So simple that it took on a life of its own. One estimate of #notinmyname's reach suggests that it touched 300 million people over the weeks since its launch on Youtube, external. Not bad for an idea born on the streets of Walthamstow in east London.

There's now a battle online between IS and, well, almost everybody else for hearts and minds.

In its earliest incarnation, IS presented the war zone as a land of jihad where one could either live in luxury or die a martyr's honourable death.

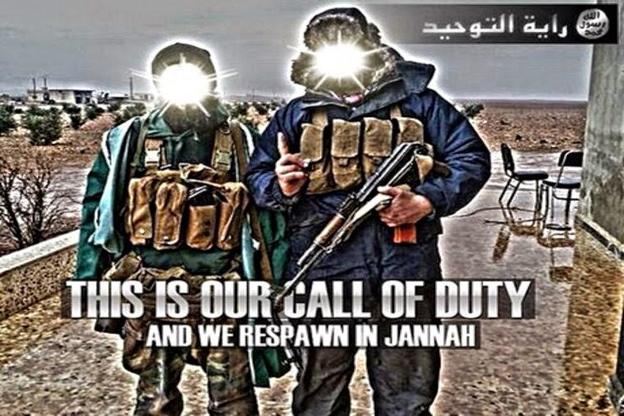

The message has become more and more extreme and violent. IS fighters linked to the UK began referencing language and imagery from video war games such as Call of Duty, making simplistic claims about "respawning" in heaven - meaning starting the game again. Back home, their supporters saw these messages, shared them and made their own plans to get a flight to Turkey.

IS uses imagery from games such as "Call of Duty" in their recruitment

Shiraz Maher and colleagues at Kings College London have conducted the most comprehensive studies so far of the online activity of jihadists in Syria.

"This is the most socially-mediated conflict in history," he says. "You literally have thousands of foreign fighters from all over the world using social media in order to convey the message about the jihad that they are fighting.

"If I am a 20-year-old kid in Bradford who is thinking about going to Syria, I can go online and talk to another 20-year-old from Birmingham, London or Manchester and find out about their experiences and have a two-way conversation with a peer who has undergone the exact same thought processes that I have gone through and has faced all the challenges that I am about to embark upon."

So how do you combat that potent threat? How do you construct a counter-narrative that counts? EU leaders met tech firms this week to discuss this online crisis - and what's slowly emerging around the world is a strategy balancing "counter-narratives" and "take-downs".

Social networks like Twitter have accelerated efforts to remove extremist accounts.

Scotland Yard detectives in the Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit are currently instigating the removal of 1,100 pieces of content a week - three quarters of them relating to Syria and IS.

The #notinmyname campaign has had an international impact

Rachel Briggs of the Institute of Strategic Dialogue advises governments and tech firms on tactics to combat online extremism.

"Some of the aggressive take-down measures when targeted and timely can have quite an operational impact," she says.

"Twitter went after Isis in a really big way after the first video of James Foley being murdered. We saw Isis on the back foot - it issued five-stage instructions to its members how to get round this - and we saw them leave Twitter to operate on other platforms."

But there are two problem with take-downs. Firstly, they deprive the security services of rich open-source intelligence. Secondly, they can be a waste of effort.

Shiraz Maher and his colleagues who are monitoring jihadist accounts see take-downs every day - but they quickly find the removed fighters operating under a new guise elsewhere.

So the online battle has to be a balancing act, say most experts - targeted take-downs and a nuanced counter-narrative.

"We need messages that will take apart the kind of narratives that extremists are developing," says Rachel Briggs.

"Isis are using the internet really effectively because they are producing compelling, short, catchy and emotionally engaging content. That is exactly what we have to do as well.

"We have tended to produce content that is appealing to us but is not going to take apart their narrative. It's the kind of content that will be cleared through government departments - messages that have made us feel good about ourselves but are not going to do anything to encourage those who are committed to jihad not to do so."

The US government has seen how this approach can fail. It launched a counter-narrative campaign on Twitter which sought to lampoon IS's use of computer game imagery. The result was something that lacked focus - and was swiftly counter-lampooned by Western IS fighters, in a way that a rebellious teenager sneers at his parents.

The US State Department's attempt to counter IS use of computer game imagery

So a new tactic may be now emerging among European governments - one that focuses on bringing would-be fighters back down to earth.

Fighters' motivations for heading to Syria are underwritten by a "very firm belief" that they will die as martyrs and go straight to paradise, says Shiraz Maher - but he says that can be undermined.

"What's interesting is to [point out to them] they they are going to essentially fight a bunch of other guys in a turf war. If you die in that are you so sure that you are going to be a martyr? That really prompts a lot of people to think again."

There is anecdotal evidence that these messages, if delivered with impact through the right channels, may work. Rachel Briggs says there is however a difficult challenge for governments.

More from the Magazine

Although it claims to be reviving a traditional Islamic system of government, the jihadist group Isis is a very modern proposition, writes John Gray.

"They definitely need to be funding this stuff and they definitely need to be helping those who would be credible messengers develop the kind of technical and messaging skills that they need. But that's where [governments] need to stop. They then need to stop trying to control the message. They have to get used to the fact that some of the messages that are going to be the most effective are going to be the least comfortable for governments themselves."

So there's a growing sense that counter-narratives will be more clearly understood - and meaningful - if they are not just polemical but also factual. Don't just tell would-be fighters that it's un-Islamic to kill hostages - explain to them that they ultimately risk a miserable pointless death themselves.

"We are not even a drop in the ocean yet in terms of our response to Isis," says Rachel Briggs. "I think there has been some very helpful momentum [since the hostages]… if one positive thing can come out of a dreadful situation like that I hope it is some momentum behind a concerted drive against Isis online."

Back at Active Change Foundation in East London, Hanif Qadir agrees and says there is one essential voice missing from the counter-narrative - disillusioned fighters. Hundreds of people may have already fought in Syria and returned to their homes in Europe - but in the UK at least, they are not talking because they fear prosecution.

"They are the most effective tool that we could ever use in tackling radicalisation," says Qadir.

"Let's work with those individuals to make sure they are not a threat to this country, but utilise their experience as an asset to this country."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.