Viewpoint: The deadly disease that killed more people than WW1

- Published

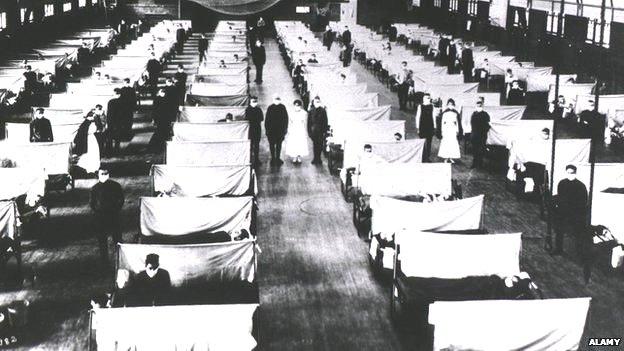

Public buildings were turned into hospitals to cope with all the cases

A deadly illness took hold as WW1 ended and killed an estimated 50 million people globally. But the horror made the world aware of the need for collective action against infectious diseases, says Christian Tams, professor of International Law at the University of Glasgow.

On Armistice Day, 1918, the world was already fighting another battle. It was in the grip of Spanish Influenza, which went on to kill almost three times more people than the 17 million soldiers and civilians killed during WW1.

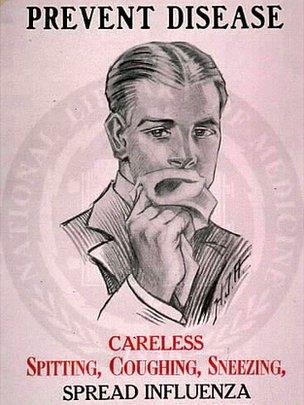

Dangerous diseases only reach the headlines if there is a risk of a pandemic, like the current Ebola outbreak. Other than that they are the largely ignored global killers, but every year they kill many more people than wars and military conflicts.

In 1918 the world faced a pandemic. Within months Spanish Flu had killed more people than any other illness in recorded history. It struck fast and was indiscriminate. In just one year the average life expectancy in America dropped by 12 years, external, according to the US National Archives.

A peace to end all wars?

After WW1, global leaders dreamed of a new world order. How close did they get? Prof Christian Tams explores whether they succeeded in a free online course (MOOC) from the BBC and the University of Glasgow. Click on the like below to learn more.

In many countries public health services responded, while societies used to wartime restrictions bore quarantines and other measures with resilience. But massive troop deployments and increased global travel meant that no nation could fight the Spanish Flu singlehandedly. Warring nations would need to co-operate if they wanted to combat global diseases.

In the aftermath of WW1 global security was the major concern. At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 the Allies redrew boundaries, carved up empires and established the first-ever world organisation, the League of Nations.

How deadly was Spanish Influenza?

One fifth of the world's population was attacked by this deadly virus

Most vicious influenza strain of the 20th Century

Deaths even surpassed the Black Death of the Middle Ages

Source: US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and BBC

The League was set up primarily to preserve peace, which it did with limited success. But it was also to be a centre for co-ordinating international co-operation. The prevention and control of disease was one of the matters of "international concern" listed in its founding treaty. And very quickly - drawing lessons from the Spanish Flu and other global diseases - the League would lay the foundations of our modern system of global healthcare control.

The League's work for international health is largely forgotten, but it is a remarkable story. Under-staffed and under-resourced, various League health agencies during the 1920s and 1930s began to view global health as a global challenge. This involved crisis responses on the ground, but also long-term work towards prevention and health education.

When the League began its work, the worst waves of the Spanish Flu were over. However, countries in Central and Eastern Europe found themselves in the grip of another disease - typhus. The League mobilised international action that by 1921 had largely managed to contain the spread of the epidemic, through mass examinations, de-lousing and bathing and the imposition of quarantines.

While crisis responses remained important, the League greatly improved work towards the prevention of diseases and pioneered health education. Early-warning systems were set up to gather information on the most common infectious diseases such as Cholera, Yellow Fever or Small Pox. This was then communicated by telegraph to a global network.

The League also promoted health-related research and standardised the use of vaccinations around the globe. And it engaged in the first global attempt at health training. This included large-scale programmes of Malaria education and a concerted effort in the 1920s to improve healthcare in China.

While little of this generated news headlines, it would be foolish to dismiss the League's work. Prevention remains the best cure and the League's efforts are likely to have saved countless lives.

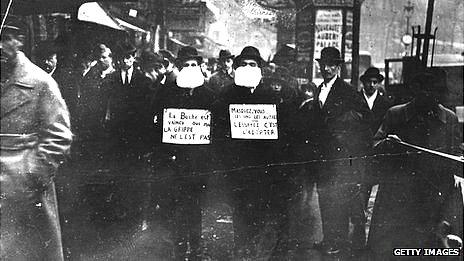

In many countries like France people were urged to wear protective masks

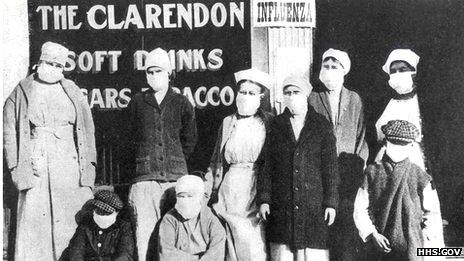

Shop staff in Chicago also wore them

As did did police officers in Washington

In an early form of public-private partnership, international health co-operation brought together League experts, national governments and private charities. All this marked no more than a beginning, but it brought home the basic idea that global health can only be protected through international co-operation.

Current reports about the likely spread of Ebola show threats to the world's health are not over. Such threats of deadly pandemics can still meet with haphazard responses.

But beyond pandemics, which are widely reported, the truly shocking figures are the ones that hardly ever reach the headlines, like that of seven million children dying every year from preventable diseases.

But global health has massively improved since 1918 and there are numerous untold success stories. Polio, one of the deadliest scourges of mankind, is nearly eradicated thanks to the combined efforts of UN agencies and private charities like the Gates Foundation and Rotary.

What are MOOCS?

MOOCs stands for massive open online courses and are a new way of learning from the world's leading academics. The BBC is launching four WW1 MOOCs, working with leading universities.

Explore the courses by registering here.

Where the League relied on telegraphs to spread information, the World Health Organization now holds the means to prepare for health emergencies. And while millions died of Spanish Flu, research and international co-operation have helped us to deal with risks of more recent influenza epidemics.

But the key challenge remains, outside dramatic outbreaks like those of Ebola today or of the Spanish Flu almost a century ago, global health too often remains a side-issue.

In a year that marks the centenary of WW1, it deserves our full attention and the League's network on global health still has much to teach us.

Find out more about MOOCs and register here. Also, discover more about the World War One Centenary.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook