The fatal attraction of lead

- Published

For millennia lead has held a deep attraction for painters, builders, chemists and winemakers - but historically it's also done untold harm, especially to children. And while it's been banned in petrol, your car still contains several kilograms of it. So have we finally learned how to use lead safely?

Element number 82 is one of a handful that mankind has known for millennia. The oldest pure lead, found in Turkey, was made by early smelters more than 8,000 years ago.

That's because lead is very simple to produce. It often comes mixed up with other more coveted minerals, notably silver. And once the ore is out of the ground, thanks to its low melting point, the lead can easily be separated out in an open fire.

One place lead has long been mined is the Derbyshire Dales, at the southern end of the UK's Peak District National Park.

Disused lead mine in Derbyshire

As well as its tourist-friendly natural beauty, the area's volcanic and limestone geology also provided the perfect conditions for mineralising the lead sulphide ore called galena.

For 100 million years the lead just sat there harmlessly, locked up in the rock. Then, 3,000 years ago, people began to dig it up. And then the Romans arrived. And soon enough boatloads of Derbyshire ingots were being shipped back to the Continent.

The Romans were the first to exploit lead on an industrial scale. Ice cores in Greenland contain traces of lead dust from 2,000 years ago, carried on the wind from giant Roman smelters. One of the largest, located in Spain, was operated by tens of thousands of slaves.

Lead found dozens of uses throughout the Empire. Being apparently insoluble, it was used to line aqueducts and make water pipes - the word "plumber" derives from the Latin for lead, plumbum.

The Romans excelled at plumbing, unfortunately they used lead pipes

"I think of it as the plastic of the past," explains Derbyshire lead mining historian Lynn Willis. "It's flexible, you can cast it into thin sheets, solder it into pipes."

The metal was malleable and seemingly impervious to corrosion, and so - just like modern plastics - it became ubiquitous. And not just in Roman times.

"In a large house in the 17th Century you might find the table covered with [lead tableware], the cisterns holding the water, the drains, the pipes."

Lead has a long association with the building trade, providing a waterproof material for roofing, window frames, and for sealing stone walls. And a heavy lump of lead on a string formed the plumb-line builders used to ensure those walls were vertical.

Peeling lead paint

The metal was found to have other magical properties. Lead carbonate, for example, has provided a cheap, durable paint since ancient times. Known today as "flake white", it was prized by Old Masters such as Rembrandt because of the steadfastness of its colour and the beautiful contrasts it would bring to their oil portraits.

Meanwhile, glassmakers learned that adding in some lead oxide would yield glassware such as wine decanters that would glisten, because the lead refracted the light across a wider arc.

Unfortunately, a leaded crystal wine decanter turns out to be a singularly bad idea, according to Andrea Sella, chemistry professor at University College London, especially if the wine (or sherry, port or brandy) is held in it for a long time.

"The lead slowly dissolves out into the wine itself. The intriguing thing is that you get a compound that used to be known as 'the sugar of lead'."

This compound, lead acetate, not only looks like sugar, it also has an intensely sweet flavour, Prof Sella explains.

"One of the curious things is that the drink that you would put into your decanter would over time gradually become sweeter."

But lead, of course, is also toxic. Once inside the body, it interferes with the propagation of signals through the central nervous system, and it inveigles its way into enzymes, disrupting their role in processing the nutritious elements zinc, iron and calcium.

And so history is littered with examples of people, often unwittingly, enhancing the flavour of their beverages with lead, with horrendous consequences for the health of the end-consumers.

The citizens of Ulm in Germany were plagued by agonising stomach cramps in the 1690s. But it was soon noted at a local monastery that some of the monks, who happened to abstain from drinking the popular local wine, were being spared by God.

The source was eventually identified as a lead oxide sweetener added to the wine - and then eliminated via what was possibly the world's first formal ban on the use of lead.

In England, these same stomach cramps became known as "Devon colic" after a similar 17th Century outbreak, this time caused by the lead used in local cider presses.

Gout could also be brought on by lead poisoning, and became a hallmark of the English nobility in the 18th Century. The apparent cause this time was the 1703 Methuen Treaty between England and Portugal, better known as the "Port Wine Treaty".

It cemented military friendship and favourable trade terms between the two nations, stimulating a booming trade in port. Guess what the wine came laced with? Lead acetate.

Lead-induced gout was all too familiar to the Romans too. They associated it with the morose god Saturn, who ate his own children.

The link was apt. Chronic lead exposure causes depression, headaches, aggression and memory loss. It can also cause sterility, and some suggest this explains the common failure of Roman aristocrats, such as Caesar Augustus, to produce a natural heir.

How were the Romans poisoned? Tiny amounts of lead in water pipes dissolve into soft water (the lime-scale from hard water stops this process). The Romans also handled lead in the form of coins, pots and dishes. And they used it in paints and cosmetics.

However, the biggest probable source was once again wine, specifically a sweetener-cum-preservative the Romans called sapa or defrutum.

Did lead poisoning help bring down the Roman Empire?

The Romans boiled concentrated grape juice down in lead pots into a syrup that helped extend the life of wines. Why lead pots? According to the winemaker Columella, "brass vessels give off copper rust, which has an unpleasant flavour."

The outcome is clear from bones in ancient Roman cemeteries, which contain lead levels more than three times the modern safe limit, external recommended by the World Health Organization.

Lead: Key facts

The Babylonians used the metal for plates on which to record inscriptions

Malleable, ductile, and dense, it is a poor conductor of electricity

Symptoms of lead poisoning include abdominal pain and diarrhoea followed by constipation, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache, and general weakness

Resistant to corrosion

Whether this contributed to the apparent madness of emperors such as Caligula and Nero, and the eventual collapse of the Empire remains a contentious question among classical scholars.

But it's clear that the Industrial Revolution unleashed a new wave of lead poisoning far greater than anything in ancient times, and this time it was the working classes rather than aristocrats who bore the brunt.

Derbyshire lead miners for example were often marked by a black line across their gums - brought on apparently by the chemical reaction between lead in the miners' blood and sulphur released by bacteria in the mouth, after they had eaten certain kinds of food, including eggs.

The worst affected were those employed in smelting or in the manufacture of lead-based paints, who found themselves surrounded daily by lead fumes.

A black line on the gums is one sign of lead poisoning

Take the Sheffield paintworks, for example. After three months at the works, employees typically developed a skull-like complexion of pallid skin and dark recessed eyes, Willis says. Melancholy, pain, infertility and death followed.

"In the 1870s, the doctor reported that six people out of 70-80 had died the previous year," says Willis. But he also noted that in his father's time in the 1830s they had died "like sheep".

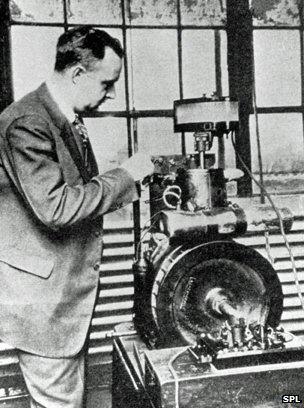

Given that lead poisoning had been around so long, the actions of the chemist Thomas Midgley Jr appear to have been reckless in the extreme. He is the man who put lead in petrol.

In 1921 as a brilliant young chemist at General Motors he discovered that adding the compound tetra-ethyl lead made engines run more efficiently, eliminating the uncontrolled knocking of early motorcars.

The product was marketed as the benign-sounding "ethyl". When challenged about the dangers of the lead content, Midgley called a press conference at which he poured the chemical over his hands and breathed in its vapour for a full minute, claiming he could do so every day without ill effect.

In reality, both before and after this incident Midgley spent months plagued by the effects of lead poisoning. GM's ethyl plant in New Jersey, meanwhile, was forced to close after several workers went mad and some died. The press renamed ethyl "looney gas".

Midgley was a tragic individual.

Thomas Midgley, creator of tetraethyl lead

Later in life he contracted polio and became bed-ridden, so he designed a system of pulleys to raise himself up - only one day he became entangled in them and died of asphyxiation.

However, the greatest tragedy was his legacy. It was Midgley who invented chlorofluorocarbons - CFCs - the refrigerant gases later found to be responsible for opening up the hole in the ozone layer and increasing the incidence of skin cancer. And cars - far more of them than Midgley could have conceived of in the 1920s - would continue to belch out lead bromide fumes for decades.

Although this was a far more dilute source of poisoning than Roman sapa or the fug of a Victorian paintworks, it was incomparably more far-reaching, affecting every city on the planet. And this time the victims were children.

It was another American, the paediatric psychiatrist Herbert Needleman, who was responsible for finally getting the lead taken out of petrol.

In the 1970s and 1980s he discovered that even very low levels of lead exposure did irreversible damage to infants, including unborn babies. As they grew up, their IQs were lower, they had trouble concentrating, and often dropped out of school.

As young adults, data suggested, they were more likely to become bullies, delinquents, criminals, teenage parents, drug addicts, unemployed, and so on. Needleman concluded that the lead had permanently weakened their ability to resist dangerous impulses, external.

Thanks in large part to Needleman's work, the US began phasing out tetraethyl lead in 1975, and most of the planet followed suit. Yet it is only now that the possible scale of the harm done by lead poisoning is becoming apparent.

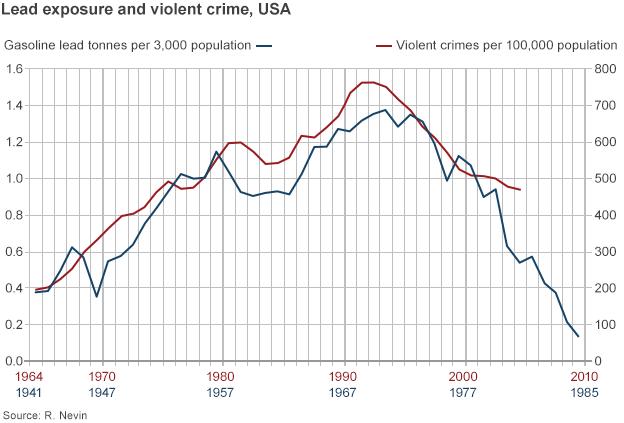

That's because many academics now believe leaded petrol was responsible for a global crime wave that peaked in the 1990s.

One such is economist Jessica Wolpaw Reyes of Amherst College in the US. "When we had leaded generations in the 1960s and 1970s, they would have been far more likely to commit crimes, especially violent crimes, in the 80s and 90s," she says.

She found that the timing of when petroleum companies phased out leaded petrol in individual US states between 1975 and 1996 mapped closely to when their respective crime statistics peaked two decades later.

Other studies looking at the difference between countries worldwide found similar results. However, the link between lead and crime is still disputed, with plenty of other explanations forwarded for the global drop in crime rates, external.

Meanwhile, the drive to eliminate lead from the environment continues. Lead paint is also on the way out. Needleman claimed that it was almost as big a source of poisoning as petrol in the modern world.

All paints, even durable lead-based ones, are prone to crumble eventually. But being a chemical element, the lead never breaks down or disappears. Instead, the dust can be inhaled, or the sweet-tasting flakes can be consumed by a curious toddler.

In the UK the ban has extended beyond bulk household paints to include artists' suppliers, such as the 150-year-old L Cornelissen in London's Bloomsbury.

"It is a traditional paint and has passed the test of many, many centuries," says the shop's owner, Nicholas Walt, ruefully. "Petrol's pretty dangerous too, but we've learned how to handle it, and it's a shame that we can't do the same with flake white."

Lead can still be found as a radiation shield at your doctor's surgery, or as a roof lining material in northern Europe. It's also being used to waterproof and immobilise subsea electric cables for offshore windfarms.

But the biggest use by far is, ironically enough, still in your car. Almost 90% of lead is used to make batteries. Some of them sit in hospitals or mobile phone beacons to provide back-up power in case the grid goes down. But most of them are used to start people's cars every morning.

Lead is not the most obvious metal for a car battery. Coming from the bottom of the periodic table, it is exceptionally dense, and a great weight to carry around - about as far from a lithium battery as you can get.

However, unlike other batteries, it will provide the initial surge of energy needed to get your engine moving, again and again for years, without breaking. Even hybrid and fully electric cars typically contain a lead acid battery to complement their main lithium or metal-hydride one.

And now for the good news: Unlike a can of leaded petrol, a lead-acid battery is a sealed unit. The lead never escapes. And that remains true even at the end of the battery's life.

"Lead has the highest recycling rate of any metal," says Dr Andy Bush, head of the International Lead Association. "The recycling rate in Europe and North America [for batteries] is 99%."

He says this isn't just because of environmental regulations. Lead is a very easy metal to recycle.

That much is clear from a visit to the HJ Enthoven recycling plant at Darley Dale - a last vestige of the Derbyshire lead mining industry.

They take lead batteries, then smash them to pieces in a contained unit. That makes extracting the metallic lead a simple task as it just sinks to the bottom. Lead is also recovered from the sulphurous electrolyte fluid.

All that molten lead is then poured into ingots that can be sent straight back to a battery manufacturer. Even the recovered plastic gets turned back into battery casings.

"It's a completely closed loop," says the plant's manager, Peter Allbutt. "This is a material that is recyclable again and again and again."

All the same, you may still be surrounded by lead that doesn't form part of this loop. It remains in some old pipes and in older layers of household paint.

Amazingly, a handful of countries - Iraq, Yemen, Burma, North Korea - continue to use leaded petrol. And there are many more countries in the world, including India and China, which are still getting to grips with the pollution from their lead smelting industries.

And in some places it's found its way into the earth.

In the Derbyshire Dales, the average lead content in the region's soil, at 0.05%, is 10 times the UK national average. In some hotspots - downwind from old smelters, or where miners dumped their spoils - it can be as high as 3%.

And it will just continue to sit there, until someone cleans it up.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.