Viewpoint: The Argentines who speak Welsh

- Published

Nearly 150 years ago a group of intrepid Welsh settlers headed to Patagonia in South America. Prof E Wyn James of the School of Welsh, Cardiff University, asks what lessons they might offer about migration and integration.

I've recently returned from a visit to Patagonia - to the province of Chubut in southern Argentina. Although very memorable and enjoyable, it was also rather surreal.

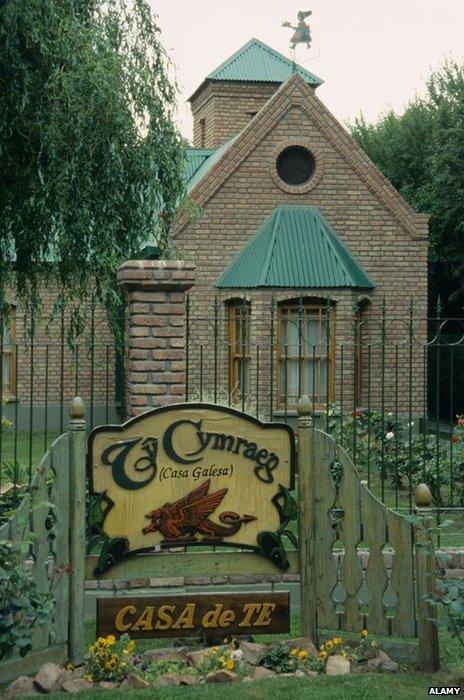

Indeed, it was a little like visiting a parallel universe. That was not just because I was leaving a Welsh autumn for a Patagonian spring, because Chubut is very different from Wales in so many ways. Yet, in the Chubut Valley, I found myself singing Welsh hymns, eating a Welsh tea, watching Welsh folk dancing, and witnessing the traditional ceremony of the "chairing of the bard" in a cultural festival we in Welsh call an eisteddfod.

The reason for this rather incongruous scenario is that 150 years ago, in 1865, just over 150 Welsh people sailed from Liverpool intent on establishing a Welsh settlement in the Chubut Valley. And although Spanish is now the main community language, there are perhaps as many as 5,000 people in Chubut today who still speak Welsh, and in recent years there has been a significant revival of interest in all things Welsh.

But why was this Welsh outpost established, and why in Patagonia of all places? The main reasons people emigrate are economic, but there are others, especially those linked to the desire for political and religious freedom, which in turn are closely linked to identity.

In the mid-19th Century, a period of political radicalism and growing Welsh national consciousness, most of the population of Wales were Welsh in language and Protestant Nonconformist in religion, all of which contrasted sharply with the ruling classes.

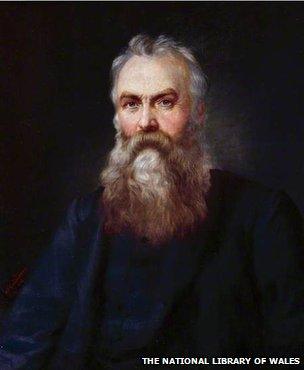

One of the most prominent among the radical Nonconformist leaders in Victorian Wales was Michael D Jones. A man of strong religious and political convictions, he placed much emphasis on the importance of nation and community. In 1848, on a visit to family members who had emigrated to America, he noticed that Welsh immigrants assimilated quite quickly into the English-speaking world around them, gradually losing their language, customs and religion.

Michael D Jones (1822-1898) by Ap Caledfryn

Many immigrants, in all periods, are happy, indeed often anxious, to put the old world behind them and forge a new identity. But for others, as we can see today, this loss of culture and identity can be a matter of great concern.

This loss of Welsh identity was a matter of great concern to Jones, and he began arguing strongly that, if Welsh emigrants were to retain their language and identity, Welsh emigration would have to be channelled to a specific Welsh settlement somewhere remote from English influences, where the Welsh would be the formative, dominant element.

He became the leader of a group of like-minded people, who attempted to realise this objective of a Welsh-speaking, self-governing, democratic and Nonconformist Wales overseas. A number of locations were considered, including Palestine, and Vancouver Island in Canada, but they eventually agreed upon the Chubut Valley in Patagonia - a remote area of South America, with no European settlements, only nomadic indigenous peoples.

Jones didn't settle there himself - he didn't really approve of emigration - the better option, in his view, was to stand one's ground in Wales itself. But he accepted that emigration was a universal phenomenon, and if it was inevitable then he was strongly of the opinion that it should be channelled to create a new Wales overseas.

Despite a very difficult start, by the end of the 19th Century the Welsh settlement in Chubut was experiencing something of a golden age, both economically and culturally. During that period Welsh was the language of education, religion, local government, commerce and cultural life in general, and it looked as if the vision of a new Welsh-speaking Wales overseas would be realised.

The first Welsh settlers landed in 1865 and lived in caves in the cliffs

But with economic success came the seeds of failure. People from other parts of the republic began to move in, the Argentine government began to involve itself increasingly in the life of the settlement, insisting in 1896, for example, that schools changed from being Welsh to being Spanish. Immigration from Wales more or less ceased with World War One, and with no injection of new Welsh-speakers from the old country, and the increasing emphasis by the Argentine Government on assimilation, the Welsh language and its culture went into steep decline in the mid-20th Century - Welsh becoming excluded from public life, and restricted to all intents and purposes to the home and to chapel. Things looked very bleak for the fortunes of the Welsh language in Chubut.

However, celebrations of the centenary of the settlement in 1965 brought increased contact with Wales, and this has grown steadily ever since. There have been changes in government policy, with less emphasis on assimilation and more on cultural diversity, and a new appreciation of the pioneering role played by the Welsh settlers. As a result, recent years have seen a significant revival of interest in Welsh language and culture in Chubut.

And in some ways, Chubut today is a mirror-image of Wales. Welsh is still used, but now (as in Wales) by a minority rather than the majority of the population. There is (as in Wales) a flourishing Welsh learner movement. You still have Welsh place-names, Nonconformist chapels, the eisteddfodau and other elements of traditional Welsh culture - but all in a very different geographical and cultural setting, and with Spanish now rather than English as the dominant, all-pervasive language and culture.

But it is important to emphasise that what we have in Chubut is a mirror image of Wales - it is not Wales.

As in all immigrant communities there are examples of descendants of the original immigrants who have embraced their Welsh roots with the zeal of the convert. However, most Argentines of Welsh descent are emphatic that they are Argentine, even though they may be very proud of their Welsh roots and supportive of Welsh-Argentine cultural activities.

-and-chapel.jpg)

Prof Wyn James (left) Prof Bill Jones and Dr Walter Brooks outside Bethel Welsh chapel, Patagonia

It is also important to emphasise that Welsh-Argentine culture, although in one sense a hybrid, is ultimately Argentine and not Welsh. One small example of the way a Welsh tradition has adapted to a very different cultural context is the "chairing of the bard" ceremony. At the National Eisteddfod of Wales, those taking part in that ceremony wear quasi-druidic robes - in the Patagonian equivalent they wear blue ponchos.

Patagonia, then, is a place where Welsh is spoken with a Spanish lilt, and where the guitar and the asado, the gaucho and the siesta are part and parcel of Welsh Argentine culture.

Identity is a complex, fascinating affair, a core element of what it is to be human, and the Welsh settlement in Chubut abounds in interesting questions about it.

The preservation of their separate identity was of sufficient importance to make many of those early settlers not only venture 7,000 miles from their homeland in Wales to the uncertainties of an unfamiliar and undeveloped region, but they were also willing to suffer untold hardships in the early years.

Their aim was to replicate Wales in South America. Ultimately that failed, partly because of the Argentine government's policy of assimilation, and partly because the numbers of Welsh immigrants never reached the critical mass needed for Chubut to develop into a self-governing, Welsh-speaking province.

But even during the early years the culture of the settlers had begun to diverge from that of the old country because of their very different social, cultural and geographical context, and this divergence would accelerate from generation to generation. As is the case with immigration worldwide, ultimately the draw of the new country is too great. Immigrant communities eventually and inevitably adapt to their new context.

Ironically the long survival of the Welsh language in Patagonia only emphasises that inevitability, because Welsh is now spoken there by people who regard themselves as Argentine, and not Welsh. And yet they are Welsh-Argentines, highlighting another aspect of identity, whether of an individual or a community.

Identity is a multi-layered and fluid matter. For while the new country ultimately prevails, the immigrant brings to the new country a flavour of the old, much as Welsh-Argentine culture enriches the mosaic of Argentine identity.

Immigration and multiculturalism are high on the agenda in many countries around the world today, including the UK. There are concerns about assimilation and identity, as there were in the time of Michael D Jones.

Jones was right in regarding immigration as a universal inevitable phenomenon. What he failed to realise was that assimilation was also inevitable, that the new country ultimately claims its own, and forges a new identity.

More from the Magazine

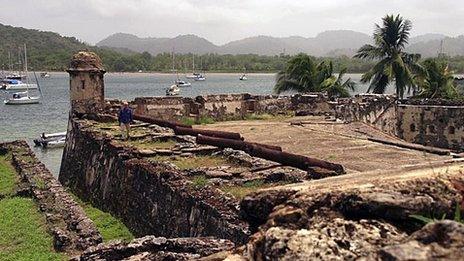

In the late 1690s an independent Scotland launched an ambitious but ultimately doomed plan to create a colony in what is now Panama. The BBC's Allan Little visited Darien, Panama, to reflect on the story.

You can listen to Migration, Separation and Wales on BBC iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.