The man who was locked up by his corrupt boss

- Published

For the past two years China has been running a very public anti-corruption drive - but it's not just crooked officials who have ended up behind bars. One whistleblower found himself in prison when he exposed his boss.

"A corruption tour? You want me to show you the worst parts of my town?"

Not exactly, we tell our humble host. We want you to show us the places that have been affected by government corruption.

He smiles and shakes his head. "It's going to be a long tour!" he jokes.

Guangshan, the town where Sheng Xingyuan has spent his life, lies in the heart of China's central Henan province. Local corruption is a serious problem across China, but Henan is renowned for dirty, insider politics that benefit a select few.

Few people are better positioned to show us around than Sheng - he's lived on both sides of China's government divide. He worked as a local Communist Party official in one of the town's family planning offices but after he caught his boss stealing government money, Sheng became a thorn in the state's side.

Celia Hatton is taken on a 'corruption tour' around Guangshan in Henan province, central China

He reported his boss, who ended up paying a small fine. Sheng faced a much harsher punishment - two years in prison.

"My colleagues took revenge on me," he explains, shaking with anger.

Sheng was convicted of "disturbing the social order". He was released after his case was reviewed by an appeals court.

That time in prison had a lasting effect. Sheng is a nervous man, still adjusting to normal life in the small room where he lives with his wife. The couple live next door to their son on the edge of Guangshan.

Sheng is obsessed with clearing his name. On a dusty laptop, he plays a secret video he recorded a few months ago, when the local party chief admitted Sheng had been framed.

"A team of prosecutors from the police and the courts were organised to fight you," the chief says on video.

"When he started talking about what really happened, I felt relieved. At least he told me the truth," Sheng says. "One day, I'll vindicate myself. I feel certain of that."

"Lots of people have been punished here for reporting corruption, like me. But if corruption isn't eliminated, no one can have peace."

China's President Xi Jinping seems to agree. Two years ago, at a Communist Party meeting, he unveiled a wide-reaching campaign to clean up the government. Many of his efforts are focused on Henan. Home to 94 million people, it's one of the biggest provinces in China. Frequent corruption scandals keep it constantly in the news.

In an attempt to unravel Henan's webs of corruption, the central government has opened more anti-corruption offices here than anywhere else.

Popular anti-corruption terms

Tigers and flies: Chinese President Xi Jinping vowed to eliminate corruption at all levels from lofty "tigers" all the way down to the lowly "flies". Some in China jokingly refer to the anti-corruption crackdown as "tiger beating" and Zhou Yongkang, the most senior official investigated, has been nicknamed "Tiger Zhou".

Throw some chilli pepper on it: Xi Jinping urged party officials to boost the anti-corruption campaign by adding "a bit of chilli pepper" to their efforts - he said they should be willing to criticise themselves and others in order to make everyone "blush and sweat a little".

Naked officials: Officials who send their families to live overseas, along with their financial assets, are considered to be a flight risk.

Four dishes and one soup: In an effort to eliminate elaborate government banquets, Communist Party founder Mao Zedong decreed that official meals should be limited to four shared dishes and one soup course. In 2013, Xi Jinping reminded cadres of this - but some reportedly get around the rules by ensuring their meals contain as many luxuries as possible, from lobster to shark fin soup.

Looking in the mirror, grooming, bathing and seeking remedies: Xi Jinping urged Communist Party officials to assess themselves by "looking in the mirror", correct any misconduct by "grooming oneself" and behave in a clean manner moving forward by "taking a bath". Corrupt officials would be punished, or forced to "take remedies".

In June, inspectors published a "problem list" they face in cleaning up Henan, and complained that the "pleasure-seeking lifestyle still exists", adding that "some government leaders team up with business owners, trading power for money."

But the locals are not focused on the luxurious lifestyles of corrupt officials at the highest levels, Sheng confides. They're more interested in the "flies" - dirty officials profiteering at the local level by demanding bribes or wasting tax money on unimaginable luxuries. One corrupt Henan party boss was found with a solid gold statue of Mao Zedong in his home.

So we decided to investigate the problem ourselves, hence, the "corruption tour".

Sheng decides we should start our expedition in a grassy field on the edge of Guangshan. The government stole the land from local peasants and sold it to developers, he tells us. We couldn't verify his claims about that particular plot, but stolen land is certainly a problem in the area. Local farmers have been known to clash with developers - the former using long knives, the latter, thugs and heavy machinery.

Then, Sheng takes us past an abandoned building in the centre of town, the glass in most of its windows shattered. Until recently, it was a brothel masquerading as a karaoke bar. It was owned by a party official, Sheng explains, but it closed when his name became public. The state media confirm his story.

Our next stop is hard to avoid. A marble-clad behemoth, the local Communist Party headquarters towers above this desolate town. Famous across China for its extravagant $16m (£10m) price tag, it was modelled after the Great Hall of the People, Beijing's main government building. The replica in Guangshan is only slightly smaller.

Down the street lies the town's main police station. "Guangshan's police chief was sent to prison for selling jobs on the police force," Sheng says. Court documents show the chief accepted thousands of dollars in bribes in exchange for promotions.

We then leave Sheng in the car as we try to track down his former boss, the official who was fined for stealing government money. Amazingly, he now works as the town's anti-corruption chief. We meet his colleagues, who graciously open the door to show us the official's empty-looking office, in an effort to prove he isn't available. Repeated interview requests were ignored.

We end the tour at a fancy restaurant popular with party comrades, in hope of spotting how corrupt officials live. But the entire restaurant is made up of private rooms, making it difficult to watch anyone else.

Sheng is fascinated by the restaurant's menu, flipping through it carefully. We learn that he's never been here before. "It's much too expensive" he shrugs.

When the food arrives, we ask Sheng if he thinks his nemesis will ever go to prison.

"If the corruption drive is real, I have to believe my boss will be caught as well," he says.

But then, he pauses, reconsidering his answer. He shakes his head. "The central government is determined, but at the local level, corrupt officials protect each other." And in Sheng's case, that seems to be true.

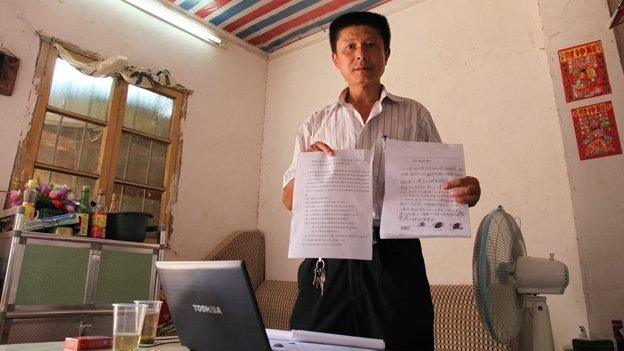

Sheng Xingyuan with some of the papers filed in his court case

At the weekend, a few weeks after we returned to Beijing, Sheng's wife called us in a panic. "He's in police detention," she said. Sheng had travelled to Beijing to petition the central government to review his case. But there, he was captured by local Henan police and dragged back to his home town.

"He didn't break any laws, he just wanted the authorities to address his case, but now, I think there is no hope."

The last time she saw her husband, on Sunday, she says several police were trying to force him to sign a piece of paper. When he refused, he was led back into the depths of the police building. She hasn't heard from him since.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published22 September 2015