Viewpoint: How WW1 changed aviation forever

- Published

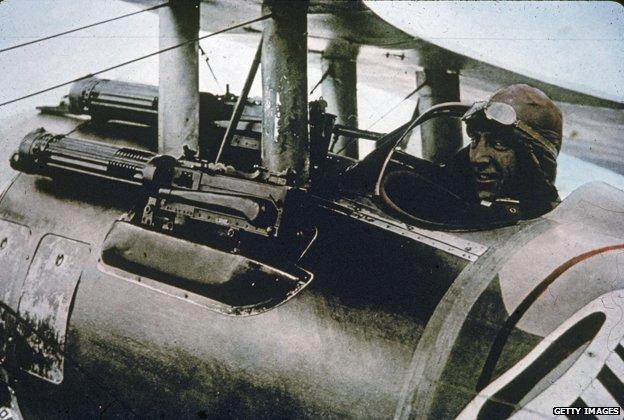

The Fokker DR-1 tri-plane was one of Germany's most famous fighter aircraft in WW1

When the world went to war in 1914 the Wright Brothers had only made the world's first powered flight little over a decade before. But the remarkable advances made in aviation during World War One are still at the core of air power today, says Dr Peter Gray.

To say the first aeroplanes used in WW1 were extremely basic is something of an understatement. Cockpits were open and instruments were rudimentary. There were no navigational aids and pilots had to rely on whatever maps could be found. A school atlas or a roadmap if necessary.

Getting lost was commonplace and landing in a field to ask directions was not unusual, as was flying alongside railway lines hoping to read station names on the platforms. But throughout the war there was a spiral of technological developments, as first one side and then the other gained the ascendancy.

To this day the core roles of air power - control of the air, strike, reconnaissance and mobility - have their roots in the evolution of aviation before and during WW1. From the deployment of Tornadoes to RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus to conduct operations against Islamic State in Iraq, to providing combat air patrols over the recent Nato summit in Wales.

How aviation came of age

Aviation evolved rapidly during WW1, with modern and more effective aircraft replacing the basic machines that took to the skies in 1914. Dr Peter Gray explores how the aeroplane turned into a machine of war in a free online course (MOOC) from the BBC and the University of Birmingham Centre for War Studies.

For the British it all started on 13 August 1914 at 08:20, when Lieutenant H D Harvey-Kelly landed the first Royal Flying Corps (RFC) aircraft to deploy in WW1 at Amiens in northern France.

This may not seem such a big deal today, but was a major achievement then - and a hazardous one. Crews were not always sure where the enemy was. The danger was all the greater because the troops on the ground were not expert in aircraft recognition so just shot at anything that flew, regardless of which side it was on.

Wing Commander PB Joubert de la Ferte remarked in August 1914 that he regretted the arrival of British troops because the RFC would be fired on by the Germans, the French and now the English.

Pilots dropped bombs by hand from planes

In the early days of war, the aircraft of the RFC were in use daily to monitor the movements of the German Army in France and Belgium. As the benefits of "eyes in the sky" became increasingly evident to both sides, it became obvious that steps would need to be taken to prevent the opposition from gaining significant advantage. The enemy would need to be shot down.

At first this consisted of little more than pilots taking pot shots at each other with their service revolvers. But as technology improved airframes became more manoeuvrable and engines more powerful and it was soon possible to mount machine guns. The age of air-to-air combat had begun.

The improvements also meant crews could carry more than simple hand grenades in their pockets. Recognisable bombs and bomb racks added a strike component to the roles of air power in warfare. This development took a sinister turn when Germany started long-range bombing attacks on London, primarily with Zeppelins and then Gotha bombers. Total war was now on the doorsteps of family homes.

Control of the air also became paramount over the trenches and has remained so ever since in every conflict undertaken.

As the war progressed, tactics and technology improved markedly with each side trying to outwit the other, both in the air and on the drawing boards of the aircraft designers.

Eyes in the sky

This was matched by an unprecedented growth in the aviation industry. By early 1915 the British Army reckoned it would need some 50 squadrons of aircraft, up to 700 planes in total. When Kitchener, as Secretary of State for War, saw the estimate he swept aside official objections with curt instruction to double the figure.

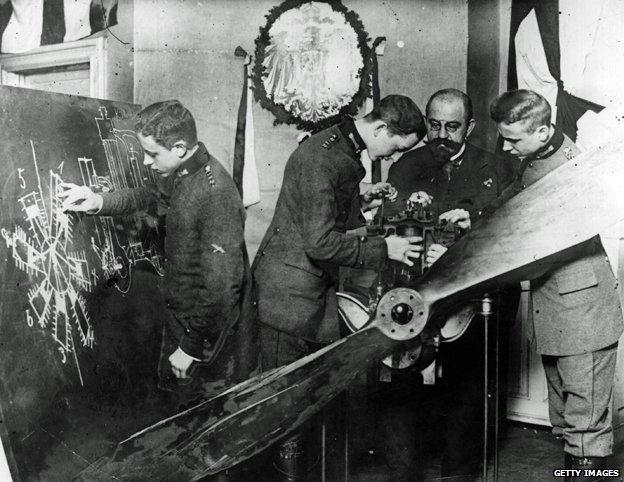

Pilots were needed in ever-increasing numbers to fly the new machines and replace casualties. Although the RFC was relatively small, their ratio of losses was at least as high as in the infantry.

But there was never a shortage of volunteers either to fly as a pilot or as an observer. The romance of flying was an attractive proposition, it avoided the tedium of life in the trenches and offered a novel way of going to war.

From today's vantage point, the aircraft of WW1 look incredibly flimsy, precarious to manoeuvre on the ground and seemingly subject to every gust of wind in the air. But to those who flew them, they were to be marvelled at. There were over 50 different aircraft designs during WW1, with five distinct technological generations, according to American historian Richard Hallion.

On all sides there was never a shortage of volunteers eager to learn to fly

The Versailles Treaty after WW1 stated German military aircraft were to be scrapped

Over the course of the war the countries involved in the fighting produced more than 200,000 aircraft and even more engines. French industry alone accounted for a third of these.

At the end of the war, the Allied nations were out-producing the Germans by nearly five-to-one in terms of aircraft and over seven-to-one in engines. The UK was producing 31 times more aircraft per month than it had owned at the beginning of the conflict and the RAF was not only the first independent air service, but also the largest.

The aircraft in 1918 were clearly recognisable as direct descendants of their pre-war predecessors with open cockpits, no parachutes and wood and doped fabric construction. But they had reached a degree of sophistication in handling and engine performance which would make a sound platform for the developments that were to come in the inter-war years and on from then.

What are MOOCS?

MOOCs stands for massive open online courses and are a new way of learning from the world's leading academics. The BBC is launching four WW1 MOOCs, working with leading universities.

Explore the courses by registering here.

As mail routes were opened and exploration flights carried out, records were set for transoceanic crossings and the pieces were all in place for an airline industry to take off, both over the then British Empire and continental land masses.

But this also had a darker side as the technology necessary to convert transport aircraft into long-range bombers was minimal. All was in place for the highly controversial bombing campaigns of World War Two.

It would then only take parallel developments in nuclear physics for the stage to be set for the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Cold War inevitably followed with the spectre of nuclear Armageddon ever present.

Pilots would shoot their revolvers at the enemy

Equally, by the end of WW1, the basic key roles of air power - control of the air, strike, reconnaissance and mobility - had all been demonstrated. They remain the same today.

Where there is a stark difference, is in the life expectancy of those involved. A century on, we still shudder at the scale of the casualties in WW1, whether in the trenches or in the air.

This obviously varied with time and activity over the war, but poet Robert Graves noted that RFC casualties were markedly higher than for infantry subalterns. Hallion quotes figures of one fatality for every 92 flying hours.

Today, living to draw one's pension is the norm. Even in hostile environments such as Iraq and Afghanistan, where the flying is likely to be either dull, dirty or especially dangerous, it is left to drones to bear the brunt.

Although still expensive to operate, they do not put aircrew in harm's way, which has made them highly popular with commanders.

The next major change will possibly be even more revolutionary than flight was a century ago. It will happen when artificial intelligence is sufficiently advanced for these machines to operate completely independently.

Will the day of the robot come, or is that a step too far?

Find out more about MOOCs and register here. Also, discover more about the World War One Centenary.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook