Yosemite's immigrant past: Asian cook immortalised

- Published

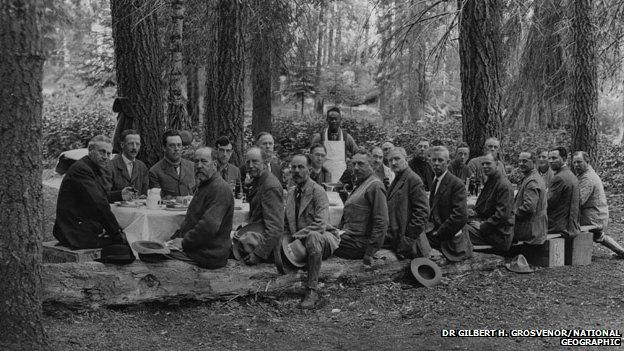

Tie Sing, standing, was well known for his culinary skill

When Park Ranger Yenyen Chan landed a job at California's Yosemite National Park, she realised how little she knew about the park's immigrant past.

So Chan, who grew up in Los Angeles with immigrant parents, dug in.

Soon stories spilled out about the critical role Chinese workers played in shaping Yosemite during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

"Some of the hardest work that had to be accomplished was getting roads up these high, steep mountains, then blasting through rocks," says Chan.

"Back then [they were] using hand tools and shovels and picks, and not the modern equipment that we have today,"

Many of the immigrant workers were road builders and lodge workers, who took on these jobs so they could send money back to their families in China.

But during Chan's research, one character in particular stood out.

In historic black-and-white photos, he's a sturdy man with a tuft of black hair, wearing a white apron.

His name is Tie Sing. He's believed to be Chinese, though no one knows exactly where he was born.

"He was the head cook for the US Geological Survey," Chan says.

Hear more

Listen to the original radio broadcast, external on PRI's The World, a co-production with the BBC.

This was a key job at the time, considering that the USGS cartographers were mapping out the park and campaigning with people like the naturalist John Muir and the first directors of the National Parks Service to preserve Yosemite.

Tie Sing would hike into the woods with these pioneers and cook up a storm.

Robert Sterling Yard, a journalist on one of those historic treks, wrote of Sing:

"To me, Tie Sing has assumed apocryphal proportions. Extraordinary recitals of his astonishing culinary exploits have been more than I can quite believe. But I believe them all now, and more. I shall not forget that dinner: Soup, trout, chops, fried potatoes, string beans, hot apple pie, cheese and coffee."

Sing also had to be creative.

Yenyen Chan looked into the Asian immigrants who helped create the park

"He had to figure out a way to keep meat fresh out in the backcountry," Chan says. "Apparently, he wrapped it in wet newspapers and put it in a place where the breeze would keep it cool."

Sing even prepared fresh sourdough bread. "He would keep some sourdough starter and, in the mornings, he would knead the sourdough and then keep it next to the mule's body so that it would rise during the day until they got to the next camp," Chan says.

Sing died in 1918, from an accident. It's not clear whether his death was related to the back country or even cooking.

In fact, it's hard to find out much about Sing or other Chinese workers in Yosemite.

"It seems like a lot of these Chinese who came, a lot of them left their families behind. So I don't know that many who ended up having kids, or grandkids, although I'm sure some of them did," Chan says.

But Sing does have a legacy at Yosemite National Park - a 10,552 foot (3,216 metre) peak, bound in granite and dotted with alpine trees, named after him.

Sing Peak is now the site of pilgrimages organised by the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California

"It's in a beautiful spot," says Chan, who has helped clear the path to the top of Sing Peak.

That effort has also sparked a new tradition: Chan now leads pilgrimages to the peak, organised by the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California.

It honours this slice of Yosemite's past and workers like Tie Sing, who once laboured where Chan now lives.

Chan says she knows she spends her days walking in Sing's footprints.

"He was somewhere really close by, and definitely travelled the trails," she says.