The nuclear attack on the UK that never happened

- Published

The 1984 BBC drama Threads depicted the aftermath of nuclear war

In 1982, a secret Home Office exercise tested the UK's capacity to rebuild after a massive nuclear attack. Files recently released at the National Archives detail one short-lived proposal to recruit psychopaths to help keep order.

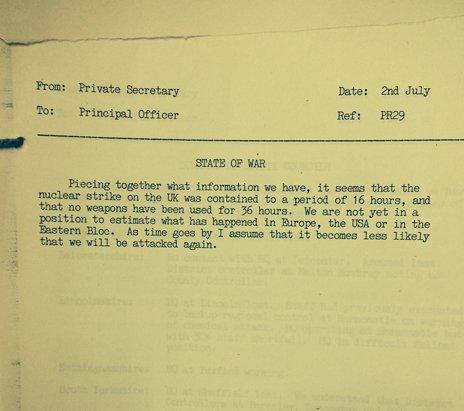

More than 300 megatons of nuclear bombs are detonated over Britain, in the space of a 16-hour exchange. Many cities are flattened - millions are dead from the blast, millions more have survived and suffer radiation sickness. In bunkers are 12 regional commissioners with their staff, ready to come out and take charge. How do they do this? How do they restore order and begin to rebuild?

This was what a top-secret Home Office exercise intended to test in 1982, according to documents recently released at the National Archives. Optimistically termed Regenerate, this was a war game covering the first six months after the nuclear exchange of World War Three. It focused on one central region, the five counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire.

Officials imagined what would happen after the bombs had dropped. They knew the most likely targets in the area, and predicted how "rings" of damage would affect the country. At the epicentres of the bombs, there would be "unimaginable" damage, on the outer ring "broken panes" and "debris in the streets". The scientific advisers estimated 50% of the country would be untouched - though survivors could be affected by radiation fallout.

Planning the war game, one civil servant tried to imagine how law and order would be maintained. Jane Hogg, a scientific officer in the Home Office, envisaged the police would be busy helping "inadequate" people in disaster-struck areas, and suggested that another group could be recruited to help keep order.

"It is... generally accepted that around 1% of the population are psychopaths," she wrote.

"These are the people who could be expected to show no psychological effects in the communities which have suffered the severest losses."

Hogg suggested psychopaths would be "very good in crises" as "they have no feelings for others, nor moral code, and tend to be very intelligent and logical".

Her bosses were unconvinced. One scribbled: "I am not at all sure you convince me. I would regard them as dangerous whether or not recruited into post-attack organisation."

The psychopath option didn't make it into the game play, which was developed by the local government operational research unit.

The exercise set out a series of local events that those involved would have to respond to as war came closer, and after the bombs fell.

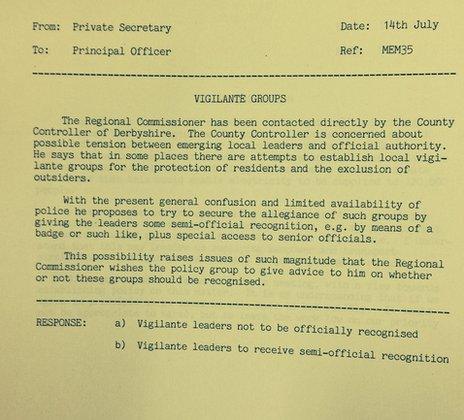

The "players", who would have been civil servants, officers from the police, fire services and military, were given choices as the scenario developed.

Clip from 1984 drama Threads

For instance, as the strike loomed, the game imagined the chief executive of South Yorkshire making "very pessimistic" public statements about survival in the event of war. Fifteen thousand families left his area and camped in nearby Derbyshire, in tents and caravans. What should be done, asked the game.

After the brief, deadly exchange, Exercise Regenerate imagined local headquarters being badly affected - Leicester bunker destroyed, HQ at Lincoln lost, HQ at Sheffield lost. Only Derbyshire, with its HQ at Matlock, was unaffected.

If this is starting to sound vaguely familiar, it's because it is very close to the plot of the award-winning BBC Drama Threads, which was broadcast in 1984. That followed the fortunes of two families in South Yorkshire, before and after nuclear war. Acclaimed at the time for its shockingly detailed portrayal of the impact of nuclear strike, it closely followed Exercise Regenerate. The drama's producer, Mick Jackson, knew about the game, and the file shows he'd made a formal request to observe it. He was turned down.

The breakdown - or disorder - depicted in Threads was how the game imagined the days and weeks after the strike. Vigilante groups emerged, challenging the authorities. Within the bunkers, morale fell. Some industry survived, but who would run it and how? The administration was weak.

In May 1982 at the Easingwold training centre in Yorkshire some officials tried to play the game. It did not work well. One player said it failed to go far enough - it was supposed to model what would happen up to 18 months after nuclear attack, but too much time was spent on the pre-strike period.

The officials went "back to the drawing board", only to discover the computer had been corrupted. That seems to have been the end of the exercise.

Lord Hennessy, author of The Secret State, said he'd never seen a civil defence exercise quite like this, where it was - albeit briefly - suggested psychopaths could be recruited to keep order after a nuclear strike. He described it as "extraordinary" and "bizarre", though noted that element was "stamped on pretty quickly".

He has seen many secret documents planning for nuclear war. "They always take my breath away," he said. "The sense of civil servants having to look into the abyss, imagine the unimaginable."

Twenty five years since the Cold War ended, most of this secret planning is known now. But Lord Hennessy said: "We still don't have the detailed plans for using the Royal Yacht as the Queen's bunker." In the event of nuclear war, he said, the yacht would be "lurking" in the sea lochs in Scotland out of reach of Soviet radar, with the Queen, Prince Philip, the Home Secretary on board.

"But I can't pick up the phone and ask the Queen: 'Can I have your Armageddon file, Ma'am?' That would be regarded as extremely bad form."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.