50 years of truly shocking drink-driving adverts

- Published

In 1964 the first drink-driving advert was fairly relaxed. Then things changed.

It's a normal Saturday, the family is looking forward to an evening of telly - Dr Who, Dixon of Dock Green, perhaps. Unexpectedly, a short cartoon appears on the small black-and-white screen. With its tinny, early electronic music, canned laughter and cartoon characters enjoying a Christmas Party, it gets straight to the point: "Drinking and driving are dangerous."

This was the country's first drink-driving ad.

It first aired on 7 November 1964, and today's viewers will find its polite approach mildly amusing, charming even. There are none of the shock tactics, car-crash carnage, gory drama associated with modern drink-driving ads. Instead, a voice with a clipped accent outlines the likelihood of having an accident after four, six, even eight whiskies. "If he's been drinking, don't let him drive," comes the warning.

With the final frame driving home the point, "Don't ask a man to drink and drive," it's easy to see the ad as somewhat sexist.

Drink drive films

However, men - particularly young ones - have been the main target of half a century of drink-driving advertising.

When the ad made its debut, the idea of "one for the road" was practically the norm. "It was the social norm for pub-going folk to drink and drive," says Gerard Hastings, professor of social marketing at Stirling University and the Open University. "In fact people would boast about getting away with it. There was definitely a sense of bravado."

Fifty years on and drink driving is viewed largely as morally abhorrent, says Hastings. Effective marketing, he says, has played a large part in changing public attitudes and habits.

In 1964, it was a crime to be in charge of a car while "unfit to drive through drink or drugs". But there was no legal drink-driving limit and no simple test to determine whether or not someone was unfit to drive. The launch of the drink-driving campaign coincided with the publication of an influential study in the US - the Grand Rapids Effects Revisted: Accidents, Alcohol and Risk.

It found that 80mg of alcohol in 100ml of blood was the level at which the chances of being involved in a crash rise sharply for most drivers. In 1967, the Road Safety Act made that the first legal maximum blood alcohol limit in the UK. It also introduced the breathalyser test. In a year, the number of road fatalities associated with drink-driving fell from just over 22% to 15%.

'Stupid Git' featuring John Altman, who went on to earn fame as 'Nasty' Nick Cotton in East Enders

But between the 1969 and 1975, the proportion of crashes where alcohol was a factor climbed steadily to exceed 35%. It seems that despite the legal framework and the introduction of the breathalyser, driving while under the influence still wasn't taboo. Indeed, in popular culture it was still viewed as being merely naughty. In an episode of the popular Return of the Likely Lads in 1974 the arrest of one of the main characters for drink-driving becomes the focus of the comedy.

It was time for some hard-hitting campaigning. The first modern anti-drink drive ads appeared in 1976. One shows a crowd of people leaving a pub to the strains of Roll out the Barrel. Moments later a woman is being stretchered into an ambulance and the normally cheerful song has taken on a menacing tone.

At the time research indicated that many people couldn't fully grasp the alcohol content of drinks or didn't fully understand the legal consequences of drinking and driving. By 1979, the total number of drink-driving related deaths was 1,640.

"In the early days, it was a learning process in terms of finding ways to change people's behaviour," says Josh Bullmore, planning director at Leo Burnett Group and co-author of the 2012 report "Department for Transport: How thirty years of drink drive communications have saved almost 2,000 lives".

But, he says, eventually there were "breakthrough moments".

In what appears to have been a nod to the zeitgeist of the 1980s, the approach in the early part of the decade was the appeal to the self-interest of the driver.

"It was the decade of me," says Bullmore. The approach was to highlight the risk to and impact on the individual - their job, their insurance. "At the time, in popular culture, on TV etc, there was a sense that drinking was part of life but rarely were the negative consequences shown."

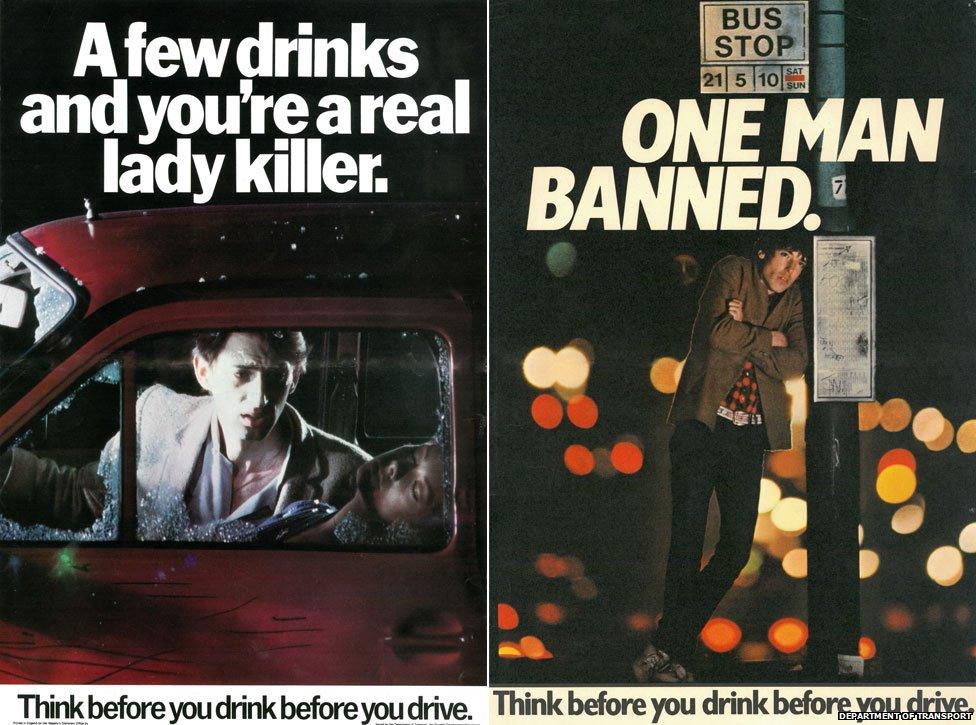

Campaigns from the 1980s aimed to show that drink-driving was not a 'victimless' crime

The ads pushed the message home with the repetition of what would happen to "you" the driver. With a conviction you will lose your driving licence, you will have to beg your relatives for a lift, you will have to wait two hours for a minicab.

Towards the end of the decade came a shift away from highlighting the consequences to the individual and to those of society. The advertisers had noted that there was still a continued social acceptability of drink driving, so the idea was to target society as a whole, to create a sense of revulsion. The message to young men was that if they drank and drove, they would be shunned by their friends and family.

The ads pulled no punches.

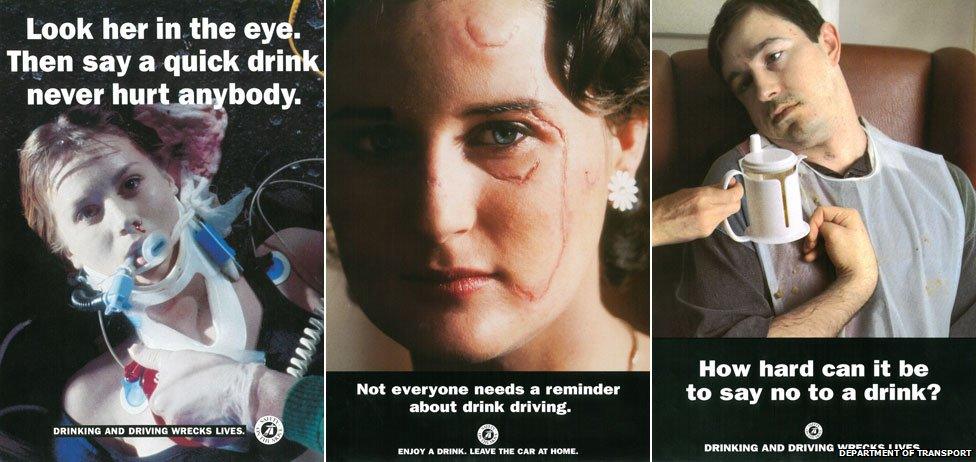

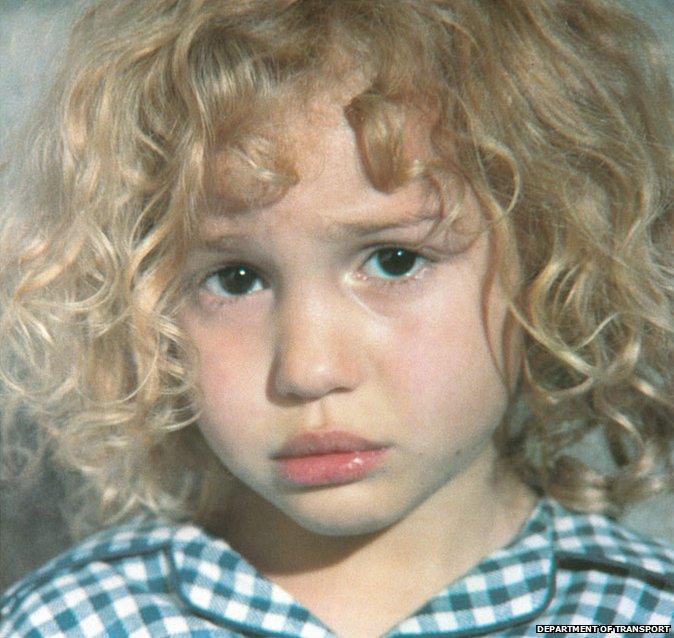

Kathy Can't Sleep and Dave were two of the most memorable from the time. The Kathy in question was a blonde-haired child, whose father had killed a boy because of driving while drunk. The intense, lingering close-ups are uncomfortable for the viewer. The slogan was: Drinking and Driving Wrecks Lives.

Kathy featured extreme close ups

Dave is a young man who has suffered brain injury in an accident. He is being fed liquidised food, spoonful by spoonful, by his mother. At the same time, the viewer hears his mother and his friends saying: "Come on Dave, just one more".

"Rather than being rational, the ads became very emotional," says Bullmore. "The campaigns went unashamedly for the heart strings." The result, he says, was "a sea change in attitudes".

But the early 1990s heralded a "culture of intoxication," says Bullmore. Alcopops took off, there was extra-strength lager and licensing hours changed. "It was a difficult backdrop," he says. "People were seeing drunkenness around them."

It emerged that young men had a strong sense that drink-driving was socially unacceptable but were failing to apply this condemnation to their own behaviour. "They would define drinking and driving with people who had something in the region of around eight pints," says Bullmore. They wouldn't see their own behaviour of having a couple of pints and getting in the car as bad.

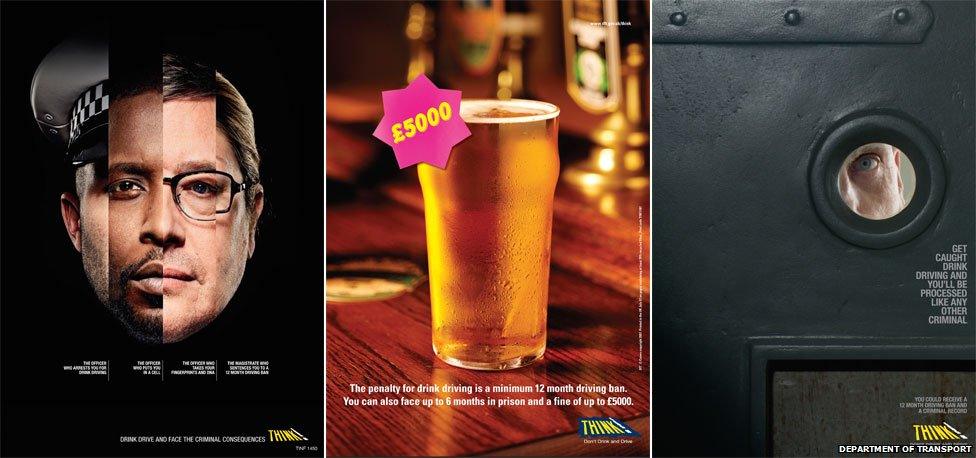

A number of campaigns focused on the consequences to the individual

The campaign focused on the "quick drink". The aim was to try to deter people from having "the second pint". One of the most memorable ads shows a group of young men in a pub drinking and eyeing up a young woman. As they settle down to another drink, the woman walks past their table. The table effectively acts as a car and rams into the woman. "It's was all about showing the immediate consequences of that action," says Bullmore.

A combination of road safety campaigning and increasingly tough laws on drink driving have cut road deaths from 1,640 in 1979 to 230 deaths in 2012.

But the fact that the Department of Transport, external is launching a new series of hard-hitting ads, indicates that while society has certainly changed over the past half a decade in its tolerance of "one for the road", there remain many who still believe it doesn't apply to them.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.