Is Spain inflating the Catalonia souffle?

- Published

Catalonia and Spain are moving apart at a fast pace, and very little is being done to bring them back together.

Until a few years ago, support for Catalan independence from Spain - independentisme - had its own steady niche of around 15% in polls and elections.

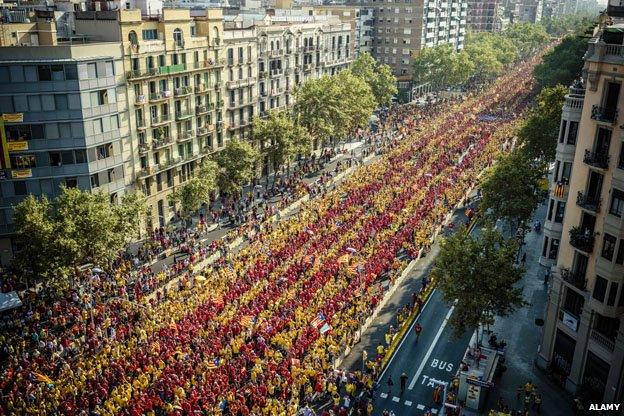

Since 2010 it has mushroomed to 45%, 50% - or, in a few polls, nearly 60%. The Catalan independence movement has also broken its own records for the largest entirely peaceful demonstrations in Europe. About 1.5 million people formed a human chain across Catalonia in 2013, and as many as 1.8 million - 23% of the population - formed a giant V (for "vote") across Barcelona in September, to demand the dret a decidir, or "right to decide", in an independence referendum.

This could be, if sustained, a ground-changing transformation. A string of reasons are commonly given for it:

The rejection by Spain's Constitutional Court in 2010 of a reformed Autonomy Statute for Catalonia that seemed to close off all established routes to change

The ongoing argument over whether Catalonia pays more to the Spanish state than it gets back

The financial crisis and austerity, which many Catalans feel are made worse by the financial constraints on Catalonia's regional government, the Generalitat

There is also a pervasive sense that the central government never listens to Catalans and treats them with contempt - menyspreu, a much-repeated word here.

The conservative Popular Party (PP) in power in Madrid under Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has a "recentralising" Spanish-patriotic agenda, and Education Minister Jose Ignacio Wert, has spoken of the need to "espanolizar" [or Spanish-ise] Catalan children.

Beneath all this, many argue further shifts are happening. Germa Bel, an ex-Harvard economist and a former Socialist MP in the Madrid parliament, used to believe in a "plural Spain" and still doesn't consider himself an independentista as such - "it's just that any other option became impossible", he argues.

There is a deep gulf of mistrust between Catalonia and the rest of Spain at an official level, Bel says, resulting in a dysfunctional relationship that prevents the solving of problems and creates endless frustration. Something, he suggests, has snapped. He and many others have "given up on Spain", and to get out of this unhealthy dead-end, he believes, Catalans need to "change parameters" and create new solutions.

A key moment came at the end of 2012, when Generalitat President Artur Mas - who comes from a party that had never previously pursued independence but only political and economic concessions from Madrid - declared his support for the "right to decide".

With official blessing, ideas of independence and above all the right to vote on the future moved from the political fringe to the mainstream. As in Scotland, the pro-independence cause has grown by going beyond the nationalist core to offer the promise of a new kind of politics, a catch-all for post-crisis discontents. The pro-vote campaign was begun by grass-roots organisations, and the unlikely alliance of political parties supporting it runs to the Candidatures d'Unitat Popular or CUP, an assembly-based, street-politics leftist movement that proposes direct democracy and "radically different institutions".

Mariano Rajoy and Artur Mas

The fundamental difference between the Catalan situation and that in Scotland is the response of the central government, which has been not political but legal. The Rajoy government insists that any referendum on independence for a single part of the country is inadmissible under Spain's 1978 Constitution, and simply illegal. For months government and Generalitat have engaged in a bizarre game of courtroom cat and mouse. To get round the ban on a full referendum President Mas and his colleagues proposed instead a non-binding but official consultation on independence, and set a date for 9 November 2014. The Madrid government still referred it to the Constitutional Court - and it was declared unconstitutional.

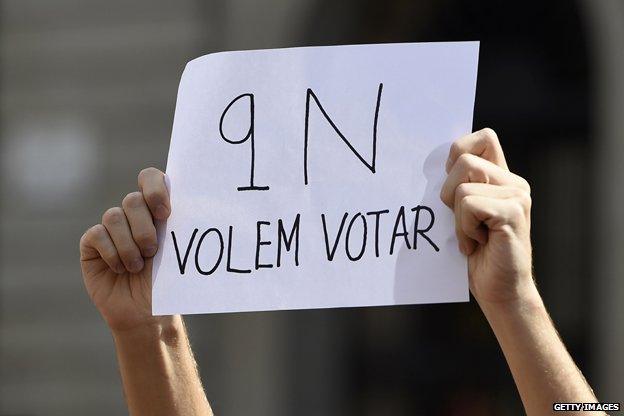

In mid-October, faced with the impossibility of carrying out any official vote without state machinery - such as electoral registers - but after months of promoting 9 November as a decisive date, Mas took a step back, cancelled the full "consultation" and announced there would only be a "process of citizen participation" in which anyone who wanted to could vote but without an official register - a widely ridiculed proposal that makes the big day only one more form of mass agitation.

In Madrid the government initially seemed inclined to let this ramshackle vote go ahead, but last week they referred this too to the Constitutional Court, which led a visibly infuriated Mas to launch his own legal action accusing Rajoy of "abuse of power".

Beyond sending in the lawyers, any political approaches by the Rajoy government or attempts to mollify any sector of Catalan opinion are remarkably hard to find. The legalist stance allows Prime Minister Rajoy to present an image of dignity as defender of the Constitution and the Rule of Law, "because without law there is no democracy". But all evidence suggests it's been counter-productive in terms of reversing radicalisation in Catalonia. If support for independence polls at around 50%, that for the "right to decide" comes in at over 80%.

More on Catalonia

Roughly triangular region in Spain's far north-east corner, separated by the Pyrenean mountains from southern France

One of Spain's richest and most highly industrialised regions

Many Catalans think of themselves as a separate nation from the rest of Spain

This feeling is fed by memories of the Franco dictatorship, which attempted to suppress Catalan identity

People are now equating three different things - the right to decide, democracy and independence - says Eduard Lopez of Esquerra Republicana, the historic pro-independence party that is the chief political beneficiary of the current crisis.

"The Spanish government's closed door to democratic dialogue has helped us a lot… and extended our support much further than we'd expected," he says.

Manel Brinquis of the Catalan Socialist Party - which does not support the unilateral "consultation", but with the Spain-wide Socialist PSOE proposes a federalist reform of the Constitution - says bluntly: "There is a machine for making Catalan independentistes - the government in Madrid."

With so much focus on the right to decide the benefits or otherwise of independence often disappear from view. Poll support for independence may hover at around 50% but that still leaves half of all people opposed or unconvinced.

The nearest thing to a locally based No campaign is Societat Civil Catalana, Catalan Civil Society. Founded only in April, it has begun to make its case - presenting, like earlier equivalents in Scotland, a disastrous picture of the potential economic consequences of separation.

Susana Beltran, its vice-president, says they speak for a "silent majority" who feel both "Spanish and Catalan", but even she suggests, diplomatically, that the government "has not known how to explain its position well".

According to Jeffrey Swartz, a Canadian art and design teacher, long resident in Barcelona and with a Catalan family, there is if not a silent majority "a big, silent minority" dubious of independence. But "nobody's ever seen a 'No' option, there's no place to say 'No'," he says.

One argument deployed by the Madrid government and its sympathisers is that the independence campaign has created a "fractured society" in Catalonia, in which Spanish-speakers are not just silent but "silenced". Behind the happy, family-based face of the pro-independence demonstrations is a steamroller intolerant of dissent, they argue.

Susana Beltran and local PP spokesman Enric Millo speak of families divided, and anti-separatists subjected to "social pressure", their children labelled "traitors" at school.

But on the streets of Barcelona - a city that is half or more Spanish-speaking, but where according to polls over half the population support a vote - a social "fracture" is hard to see. Socialist Manel Brinquis from Hospitalet, a town with a 75-80% Spanish-speaking population, and so, supposedly, most hostile to nationalism, says "there is concern", but no great alarm.

"There are arguments in families that can get tense, but social conflict, no," he says. "This intolerance is a myth."

Pro-independence and anti-separatist demonstrators shout slogans outside the Catalan Parliament in September

One feature of the Catalanist movement that its followers point to with pride is that it has used entirely peaceful and democratic means - violent incidents have been very rare and small scale. Nevertheless Jose Maria Aznar, former PP prime minister, has claimed that "identity-based nationalism" sought to "finish with democracy".

Extravagant comparisons are also routinely made between Catalanism and Nazism. In early October a European Parliament MEP for UPyD, one of the anti-Catalanist Spanish parties, sent a letter to every member of the parliament claiming that the current situation in Catalonia was similar to "Italy and Germany in the 1930s". This provoked an angry retort from a German CDU MEP, who said the comparison left her "speechless" and demanded an apology for this "trivialising of the Nazi regime".

In Catalonia these arguments do nothing to reduce feelings of menyspreu.

Catalanists are still determined to hold some kind of vote, even in the street, on Sunday.

With their own poll ratings in free fall across Spain, due to an avalanche of corruption scandals, Rajoy and the PP have perhaps even more of an incentive to stay firm to pick up anti-Catalan votes in other regions.

In Catalonia, some put their faith in a change of government in Madrid next year, but if the stand-off continues others propose a "unilateral declaration of independence" or mass civil disobedience. Another plan would see all pro-vote candidates standing in regional elections next spring on a manifesto with just one point - a vote on independence. If they won, they would then have a clear democratic mandate that the Spanish government could not deny.

In August "government sources" were quoted as claiming that a No vote in Scotland's independence referendum would "deflate the Catalan souffle". Since then, says Eduard Lopez, the government's policy has only been "inaction, and hoping the souffle will go down". But he adds: "Whatever happens on 9 November, this thing is not going away."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.