The students who feel they have the right to cheat

- Published

Students are often keen to exercise their rights but recently there has been an interesting twist - some in India are talking about their right to cheat in university exams.

"It is our democratic right!" a thin, addled-looking man named Pratap Singh once said to me as he stood, chai in hand, outside his university in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. "Cheating is our birthright."

Corruption in the university exam system is common in this part of India. The rich can bribe their way to examination success. There's even a whole subset of the youth population who are brokers between desperate students and avaricious administrators.

Then there's another class of student altogether, who are so well known locally - so renowned for their political links - invigilators dare not touch them. I've heard that these local thugs sometimes leave daggers on their desk in the exam hall. It's a sign to invigilators: "Leave me alone... or else."

So if those with money or political influence can cheat, poorer students ask, why shouldn't they?

They make other arguments too. When I was working in western Uttar Pradesh, Singh ushered me into the bowels of a smoky canteen in the middle of his campus. Kicking a stray dog off a chair, he took out a packet of cigarettes.

"India's university system is in crisis," he began, lighting up and blowing the smoke towards the ceiling. "Cheating happens at every level. Students bribe to get admission and good results. Research students get professors to write their dissertations. And the professors cheat too, publishing articles in bogus journals."

I sympathised with Singh. On one occasion, the registrar at a college in Uttar Pradesh sent masters students' dissertations to be graded by students at another college. This type of thing is common, but in this case, school pupils ended up marking masters-level work.

"I honestly don't know whether to laugh or cry," he said, hunched over the Formica table in the canteen and shooing away the flies. "The equipment in our science labs should be ripped out and thrown down a well," he added. "It is like universities were in the 1950s in Britain."

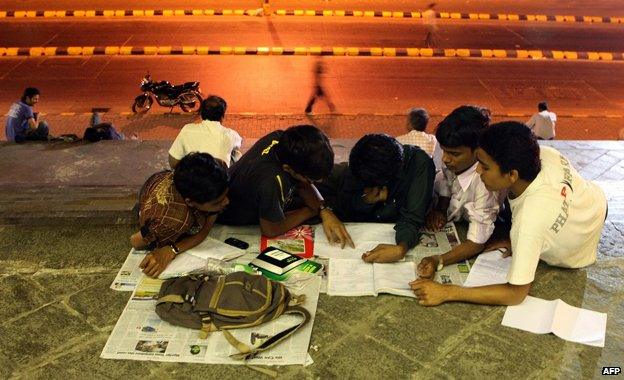

Refusing to cheat, many students work into the night to pass entrance exams

A while back, I brought up the topic with Pinki Singh, in the female hostel of a prominent college in Uttar Pradesh. We were sitting in a space that was half study area and half courtyard for urban livestock.

"I will tell you about education," she said. "The curriculum is poor, and when lecturers won't teach properly, you have to get private tutorials or just memorise from textbooks."

"If you really want to know the truth," she added, "there's no point in studying properly. You just need to buy one of the cheat books sold in the bazaar and learn the answers."

"In my first year doing history I tried to study properly, but my seniors just told me: 'Buy the cheat books.'"

Some of the new private universities are no better. She told me about one that was established recently, calling itself Zap University.

Students paid large sums of money to enrol online, but then the university just disappeared from the internet. It had no physical location and no trace could be found on the web. Pinki Singh told me: "It just went 'zap'".

As I think back to these conversations, I conjure up in my mind an image of the universities I've seen in Uttar Pradesh. Etched in my memory are mouldering books, leaky hostels and bare lawns.

And then I remember the signs of opulence that surround some of this decay. The expensive SUVs and three-storey houses of the principals, the fancy shopping malls and the few universities in the region that are genuinely offering world class education - their flashy signboards and glass fronts mocking the ordinary colleges.

The question is, what's the solution? When pro-cheating rallies were held in Uttar Pradesh in the early 1990s, the state's chief minister gave in to demands and repealed an anti-copying act - he actually allowed students to cheat.

Prime Minister Modi's approach is different. He's trying to change things. There is a new regulation system for higher education. Funding for universities increased by about a fifth in the most recent Five Year Plan from central government.

But such reforms are like a cumin seed in a camel's mouth. And anyway, delivering education is the job of Indian states rather than central government, and states like Uttar Pradesh are not investing properly in provincial universities.

This leaves many students marooned by modernity, clinging to the sinking ship of an outdated university education. The right to cheat agitation is no oddity - it is an ironic comment on India today.

Craig Jeffrey is Professor of Development Geography at the School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.