Viewpoint: Why God was not killed by the Great War

- Published

It's a popular belief that the slaughter of World War One led millions to turn away from religion. But that's not true, writes author Frank Cottrell Boyce.

The Remembrance Service at the Cenotaph is the nearest thing Britain has to a truly national religious moment. That shared two minute silence must surely be some kind of prayer.

But there's a paradox. It's a religious - or religious-like - ceremony that commemorates the war that is supposed to have killed religion. And it's an act of remembering in which much is forgotten.

"What you have to remember, is that these people had the same hardware as us, the same bodies, but very different software," says Dr Michael Snape, reader in religion, war and society at Birmingham University.

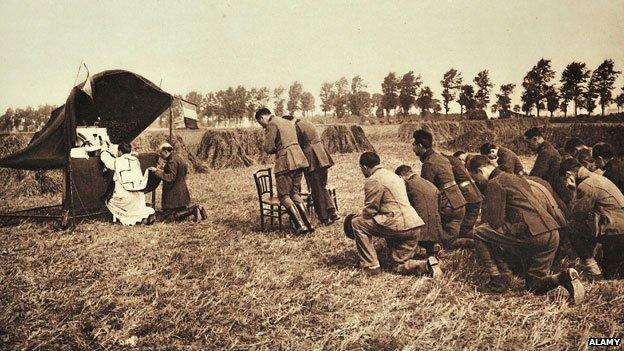

Soldiers often buried their friends

That software was religion. The men who fought in World War One were products of the Victorian Age. They would all have gone to Sunday School. Their outlook was informed by Christianity.

Churchmen in 1914 were lamenting the decline in churchgoing, as churchmen always do. But religion at the beginning of the war was in pretty good shape, says Snape. And the idea that people were alienated from the churches because of the war is a retrospective reading of history.

"We have a tendency to be condescending about our forebears," says Snape. "We're tempted to think we are cleverer than they were. Their religious beliefs seem to be part of their fateful and fatal naivety. But we shouldn't be so willing 100 years after the event to muscle in with our own interpretations of the war, to impose our standards and reactions on them."

We remember the Great War publicly, lavishly every year. But we remember it through the patina of what it has come to symbolise for us - waste, and futility.

At the front line

We remember it through the anger of its soldier-poets and - tellingly - through the comedy of Blackadder. Because this is the war whose tag-line - "the war to end all wars" - was so tragically wrong, it's actually funny. Or at least absurd.

But that's not how it felt at the time. Many understood the call to war as a call to sacrifice, believing that the laying down of their lives could make the world a better place.

Some of the lads who marched away thought they were off on a great adventure which would be over by Christmas. None of them knew that their war would have a number after its name - that there was going to be a sequel.

The more we remember, the more we forget. We forget for instance the 1.3m soldiers from the British Empire who came and fought in Europe.

Hospitals in Brighton cared for over 12,000 soldiers from India. Those that died were cremated on specially built ghats on the South Downs.

Then there are the women munition workers. A secret factory in Gretna housed 8,000 young women - 80% of them unmarried - who did the deadly work of creating cordite, the propellant for shells.

Cordite was basically cotton wool marinaded in nitro-glycerine. It was called the Devil's Porridge. When she visited them the writer Rebecca West said they were in as much danger as any soldier on the frontline. The nine-mile long factory has vanished now and who remembers the Gretna Girls?

In the Devil's Porridge Exhibition, just outside Gretna, you can see the girls' autograph books. The silly poems and aphorisms that fill them are full of longing for home, for courtship and for things to go back to normal. One of them contains this poem about church going:

Some go to church just for a walk

Some go to church to stare and laugh and talk

Some go to church to meet a friend

Some go to church some spare time to spend

Some to scan a robe or bonnet

And to price the ribbon on it

Some go there to snooze and nod

And few to meet and worship God

This is the other thing we have forgotten. Religion was the environment in which the World War One generation lived. The main meeting points of their lives and the parameters of their identities were defined by religion. It was not just how they made sense of what was happening to them, it was where they met, how they communicated, how they measured time.

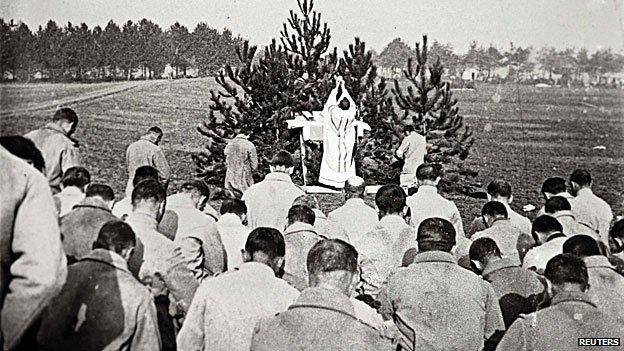

Remembering the fallen

The Young Crescent - a beautifully produced monthly magazine from the Crescent Congregationalist Church in Liverpool - ran right through the war, bringing news from the Front back to the community at home and sending messages from home to the boys at the Front.

The text is in an elegant copperplate - the handwriting of the Sunday School teacher Mr Muir. Through the copies of the magazine, it is possible to trace the painfully beautiful story of The Order of the Ginger Knut - a group of young men who enjoyed one last Lancashire walking holiday before going off to war.

They invented their own ritual - a kind of confectionery Eucharist - in which they all placed a biscuit on their tongues at the same time and thought of home, and of Christ. There are letters in the magazine in which the boys fret about the time zones, wanting to make sure they really were performing this ritual at the same time.

This parochial theological creativity finds an echo in the wider Church as it struggled to come to terms with the conflict. Ever since the Reformation, the English Church had forbidden the saying of prayers for the dead. The dead were, after all, dead. They had faced the Last Judgement and gone either to the left with the goats or to the right with the sheep. What was the point in praying for them?

During the Great War, however, that historical, moral and theological objection began to crumble under the sheer weight of dead bodies, burned or lost far from home. Sons that no-one had the chance to bury, or to say goodbye to.

At home shrines started to appear around the country

People responded to this need in various ways. There was a massive rise in interest in Spiritualism and in the geography and sociology of the afterlife. Across the country people began to create little shrines to their lost ones.

They were the forerunners of the Cenotaph and of the memorials that are a feature of more or less every settlement in these islands. It's fascinating to watch the official Church make its pastoral accommodation to the emotional needs of the people, in spite of its theological objections.

As it happens, Martin Luther, himself, did write a prayer for the dead. I find its simplicity and humility deeply moving.

Dear God, if the departed souls be in a state that they yet may be helped then I pray that you would be gracious.

But in the end - as the armistice commemorations of 1919 discovered - silence is surely our best response. The silence of not knowing but hoping, of not understanding but accepting. The silence of listening.

Find out more about the World War One Centenary and chaplains on the front line.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.