The great Victorian beard craze

- Published

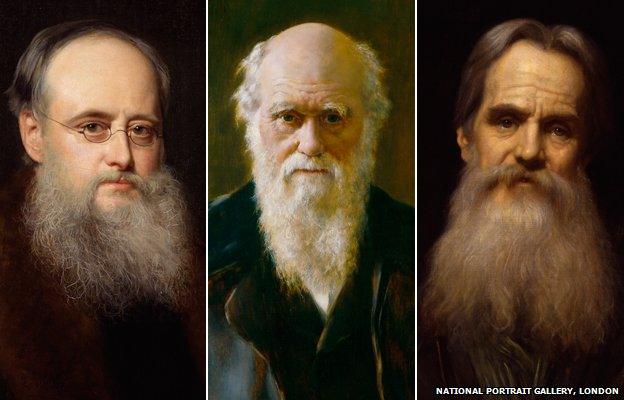

Wilkie Collins, Charles Darwin and William Holman Hunt

The beard fashion of the past 10 years on both sides of the Atlantic mirrors an earlier facial hair craze, which started during the Crimean War, lasted for three decades, and was only entirely stamped out with the invention of the disposable razor in the early 1900s, writes Lucinda Hawksley.

In the mid-19th Century, men throughout North America and Europe began doing something most had never done before. They abandoned their barbers, left patented safety razors rusting on bathroom shelves and began growing facial hair.

They were not merely growing the well-coiffed whiskers and neat moustaches hitherto deemed acceptable, but cultivating enormous whiskers that connected to huge, bushy beards and left just about enough space between them and the ever-expanding moustache to allow the owner to eat and speak.

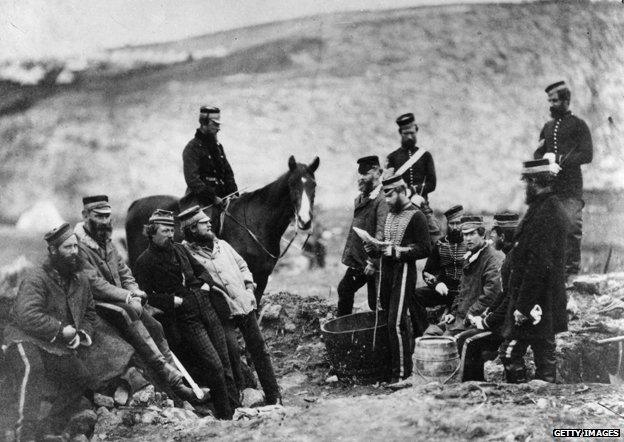

In Britain the return of the beard (the full beard had last been in vogue in Tudor times) was thanks to the Crimean War of 1854-56. Beards had been banned in the British army until this time, but the freezing temperatures of Crimean winters, and the impossibility of getting shaving soap, led to a necessary change.

By the time the last troops returned home, beards were the mark of a hero. Men who had never seen any military action began to grow beards. Within a few years, it was almost impossible to see a beard-free male face in Victorian Britain - except in Buckingham Palace, as Prince Albert refused to conform to the fashion.

Crimean War 1854-56

Fought on the Crimean peninsula by a Franco-British alliance supporting Ottoman Turks against Russian forces

The infamous Charge of the Light Brigade occurred on 25 October 1854 during the Battle of Balaclava

Thousands died of cholera during the siege of Sebastopol, which ended the war

In America, the return of the beard began at around the same date. This was partly fuelled by fashion plates from British magazines, which were read avidly in America for the latest word in European fashion. Many American men, however, also decided to stop shaving for a practical reason. Although the so-called safety razor had been around since the 1770s, they were difficult to use and often dangerous. Even men who had mastered the art of shaving, were at risk if their razor hadn't been scrupulously cleaned. One such victim was John Thoreau, brother of the writer Henry David Thoreau, who cut himself shaving and died of lockjaw in his brother's arms.

In 1861 a new word came into usage in Britain, when Our American Cousin, by Tom Taylor, had its London premiere (the play Abraham Lincoln was watching when he was assassinated in Washington DC four years later). One of the characters, Lord Dundreary, was a comic fop with prodigious side whiskers. These quickly became known as "dundrearies", a name used both in Britain and America. In England, however, they were also referred to as "Piccadilly weepers", because these whiskers were worn by the kind of dandy who could be seen in London's Piccadilly.

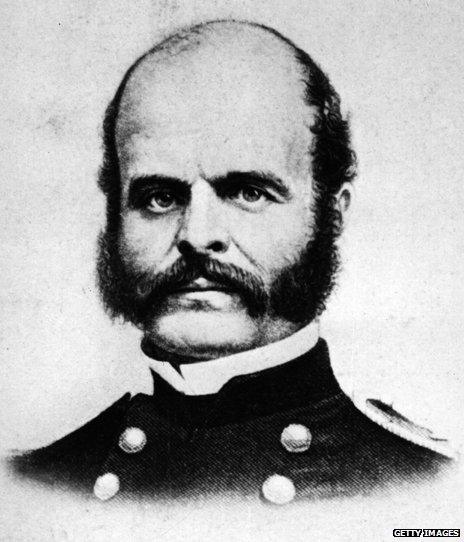

During the American Civil War of 1861-5, the word "sideburns" was coined. It was a tribute to Maj Gen Ambrose Burnside, whose bushy moustache had been allowed to connect with his whiskers and formed an impressively thick and unbroken line of hair right across his face.

The term "mutton chops" also entered the vocabulary, describing whiskers that were thin at the top and bulged at the bottom, where they were shaved to resemble a chop of meat.

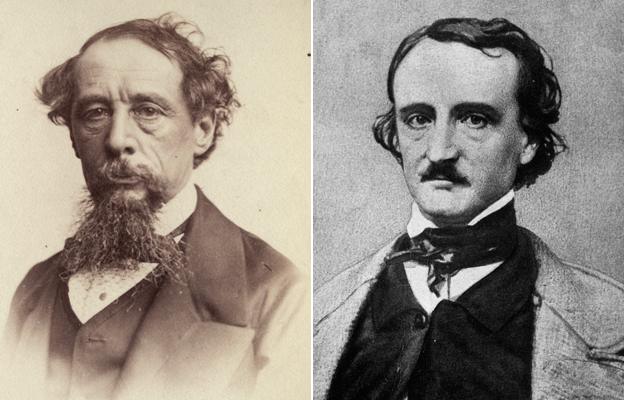

In 1842, Charles Dickens had travelled to North America for the first time and was introduced to many fellow writers including Edgar Allan Poe, with whom he remained in correspondence. Perhaps it's a coincidence, but both Poe and Dickens began to experiment with facial hair at around the same time - a moustache at first, without a beard. In 1844 Dickens wrote to his friend Daniel Maclise about his new passion: "The moustaches are glorious, glorious. I have cut them short, and trimmed them a little at the ends to improve their shape. They are charming, charming. Without them, life would be a blank." Poe grew his famous moustache in 1845, four years before his untimely death.

It took 25 years for Dickens to visit the US again - largely due to the fury surrounding his unflattering portrayal of the country in Martin Chuzzlewit and American Notes. By the time he returned, in the winter of 1867-1868, he was a global superstar and everything about him was noted and emulated. His beard, already famous, was captured in all its glory by the photographer George Gardner Rockwood in New York city - studio photographers often took pictures of celebrities free of charge, in return for permission to sell copies to fans. The pictures of Dickens were hugely popular and the style of his facial hair spawned imitators all over the world, copying what has become known as his "doorknocker beard".

Charles Dickens in the 1860s (National Portrait Gallery, London) and Edgar Allan Poe c1845 (Getty Images)

By the end of the 1880s, fashionable men in London were returning to their barbers for a daily shave. The beard and full whiskers were now considered the domain of the conservative, older generation. In the US and in Britain, the practice of being hair-free was about to become much easier and cheaper thanks to American inventor King Camp Gillette. In 1895 he came up with the idea of the first disposable razor blade. It took six years - and much pain - to perfect his invention, but in 1901 he managed to persuade others to try it out. The disposable razor was a sensation and the patent was granted in 1904. Gillette's simple invention spawned a multi-million-dollar industry for the company that still bears his name. It also coincided with increased scientific understanding of the existence and spread of bacteria.

Beards came to be targeted by medical men, and people were talking everywhere about the potential risk that beards carried in the workplace, particularly where food was prepared. In 1902, New York dairymen were banned from having beards. Dr Park from the Board of Health was quoted as saying: "There is real menace to the milk if the dairyman is bearded… The beard, particularly when damp, may become an ideal germ-carrier."

The fashion for beards, whiskers and bristling moustaches fell into a serious decline for much of the first half of the 20th Century, not least because in both world wars, the seal on gas masks would only work on hair-free skin. But one pogonophile grew a beard that hipsters of today can only dream of. His name was Hans N Langseth, a Norwegian who had emigrated to Iowa, and he grew what is believed to be the world's longest beard.

Although Langseth died in 1927, he was back in the news in 1967, when the Smithsonian purchased his beard, external - all 17.5 feet (5.3m) of it. But those tempted to follow Langseth's example should perhaps beware the fate of another bearded Hans. In 1567, a terrible fire broke out in the Austrian town of Braunau. The mayor of the town was Hans Steiniger, whose beard was so long he wore it wrapped around his waist. Unfortunately, on the night of the fire, he either didn't remember to wrap it around him, or perhaps it became untucked. He died of a broken neck after tripping over his beard while fleeing the fire.

Clippings from the Magazine

Ram Singh Chauhan of India is the proud owner of the world's longest moustache, officially recorded by Guinness World Records as 4.29m (14ft) long. But what is the secret of his success, ask Rupa Jha and Bethan Jinkinson.

Lucinda Hawksley is the author of Moustaches, Whiskers and Beards, published by the National Portrait Gallery last month. She is a great-great-great-granddaughter of Charles Dickens.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.