What explains the continuing fascination with Charles Manson?

- Published

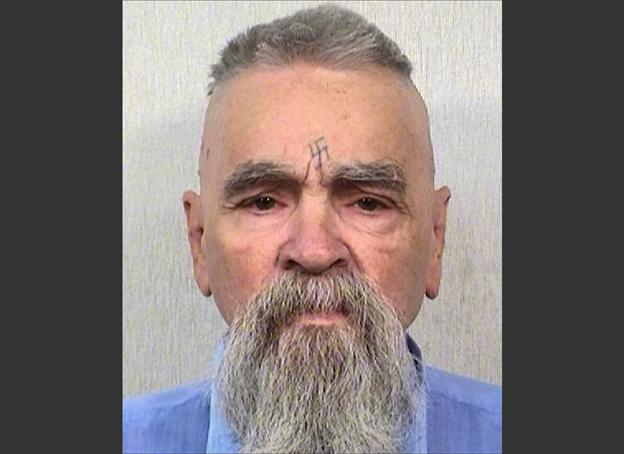

A recent photo of Charles Manson, now aged 80

What is it about the murderous cult leader Charles Manson, who committed his crimes more than 40 years ago, that continues to fascinate?

The stare is still the same. The hair may have greyed but the beard remains. With a swastika etched between his eyes, Charles Manson maintains an aura.

It is almost 45 years since he sent a group of his indoctrinated followers - known as the Family - to the home of heavily pregnant Hollywood actress Sharon Tate to "totally destroy everyone in it". She and four others were stabbed to death.

False clues were left to dress the scene as an attack by the Black Panthers, a militant African-American group which used violence in its battle against white racism.

Manson's hope was that these murders, and the killing of two shop owners the next night, would start a race war, after which he would emerge as America's ruler.

It did not happen. Amid public revulsion at his crimes, Manson was found guilty of conspiracy to murder in 1971 and given a life sentence.

Now aged 80, Manson has been granted a licence to marry Afton Elaine Burton, a 26-year-old who moved from the Mid West to live near the prison where he is an inmate in Corcoran, California. "I love him," she declares. "I'm with him." But that closeness is unlikely to extend to living with Manson, who isn't eligible for parole until 2027.

"Why does a 26-year-old woman want to marry him?" asks Daniel Kane, a lecturer on American literature and culture at Sussex University. "It shows the continuing attraction that he has for a counter-culture to this day. Manson the rebel, the outlaw, the radical vegetarian willing to kill to make his point.

"That's disgusting and demented, but it's also fundamentally political, in the same way a contemporary terrorist is political."

Actress Sharon Tate, the most high-profile victim of the "Manson family"

Sharon Tate's sister Debra, who acts as a spokeswoman for the families of Manson's victims, has called the impending marriage "ludicrous''. But this and other stories about Manson still get reported across the world's media.

More than 30 books about his life and crimes have been published. One, by the prosecuting attorney at his trial, Vincent Bugliosi, has sold more than seven million copies since 1974.

Manson's comments are widely quoted. He insists he is a "political prisoner" and that the US government is holding him hostage, proclaiming: "My father is your system... I am only what you made me. I am only a reflection of you."

Born in Ohio, Manson had an impoverished and troubled childhood. With a reportedly high IQ, but unable to read or write properly, he moved between reform schools. When he was five his mother and uncle went to prison after they held up a service station. By the age of 13 Manson was robbing casinos and shops at gunpoint.

He had "a tendency towards moodiness and a persecution complex", according to a psychologist who described him as "aggressively anti-social" partly due to "an unfavourable family life, if it can be called family life at all".

When he couldn't afford bills or support his pregnant wife, he became a thief. After six years in prison, he was released in 1967, the year of the so-called "summer of love".

Manson developed a fixation with the Beatles song Helter Skelter. Ostensibly about the difficulties of a love life told through a metaphor of a fairground ride, he instead thought it predicted an apocalyptic race war after which he and his followers, taking refuge in an underground city in California's Death Valley, would be the only white survivors. Black people, he thought, would be unable to organise themselves and then beg him to be their leader.

Manson set up a commune at the Spahn ranch in the Californian desert, surrounded by disused sets from 1950s Westerns. He recruited followers, mainly middle-class and female, with whom he took LSD and participated in orgies.

"He managed to exploit the hippy subculture brilliantly," says Kane, "Hippies, after all, proposed themselves as disaffiliated from the political and social mainstream, committed to creating their own independent utopias marked by sex, drugs and rock and roll.

"Manson took on all those signs - LSD, music, free love, communal lifestyles - and reframed them as tools for apocalyptic mass murder. Totally bizarre, totally evil, and very, very seductive."

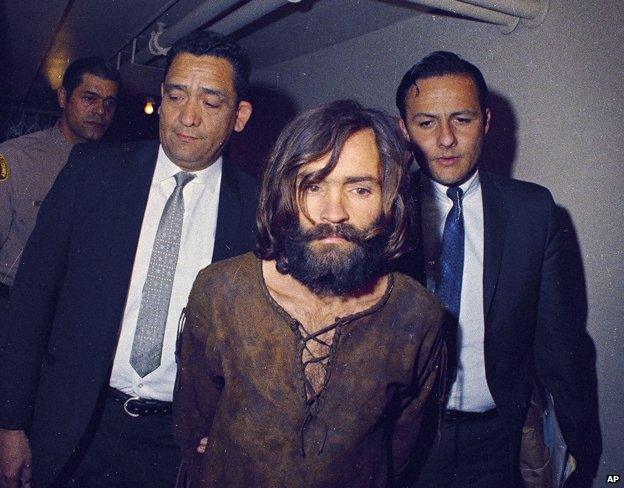

With his long hair and beard, Manson's followers likened his appearance to that of Jesus.

"There are thousands of evil, polished conmen out there, and we've had more brutal murders than the Manson murders," Bugliosi, the prosecuting attorney at Manson's trial, told Rolling Stone magazine in 2012, external, "so why are we still talking about Charles Manson?

"He had a quality about him that one thousandth of 1% of people have. An aura. 'Vibes,' the kids called it in the 60s. Wherever he went, kids gravitated toward him."

Psychopaths are "incredibly charming and persuasive", says David Wilson, professor of criminology at Birmingham City University. "To get you under control, to court you, they appear to give their complete and utter attention."

Helter Skelter

Track from Beatles' 1968 White Album - one of several songs which Manson told his followers prophesied an apocalyptic race war; the words were scrawled in blood on the refrigerator at the home of two of their murder victims

Association between Manson and the song persisted after his conviction - it provided the title of a 1974 memoir by the prosecutor in Manson's trial, Vincent Bugliosi

U2 covered song on live LP Rattle and Hum - singer Bono introduces it with the words, "This is a song Charles Manson stole from The Beatles. We're stealing it back."

There was a sense of bewilderment and terror at Manson's crimes - how an ex-convict from a poor background had managed to style himself as a guru and persuaded middle-class youngsters to do his bidding.

The Manson case involved drugs, orgies and cults, three concerns shared by parents of children growing up in the "free love" atmosphere of the era. It also came at a time of intense divisions in the US over civil rights, race and the Vietnam War. Rioting had affected several cities in 1968.

Wilson thinks Manson's persistence as a cultural figure is because he seemed to be teaching Americans about their own negligence to threats they apparently faced. This, plus his personal charisma, made his impact greater than that of most murderers.

"He is iconic because he was the person who brought the swinging sixties to an end," he says. "His strange and bizarre thinking appeared perfectly in tune with the damaged side of drug culture. It wasn't flower power any more. Youth culture was far darker and more disturbing than people had previously thought."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.