Phil Hughes: Could head injuries be eliminated?

- Published

Australian cricketer Phillip Hughes has died after being hit on the head by a cricket ball. Can helmets ever offer total protection?

Cricket is often caricatured as a slow game, with action limited to a few seconds at a time. But top-level batsmen have to stand in front of a hard ball, which weighs between 155.9g and 163g (5.5 and 5.75 ounces), external, delivered at speeds sometimes in excess of 90 miles (145km) per hour.

Hughes died only two days after being placed in an induced coma in a Sydney hospital. This follows surgery he underwent after being struck on the neck or the back of his head. This area was unprotected as it was beneath the bottom of his helmet.

Safety design has improved in cricket - where helmets only became standard relatively recently - and other sports. But could this go further without making equipment too cumbersome to use?

"We believe there's more that can be done," says Rene Ferdinands, head of cricket biomechanics research at the University of Sydney. "It is possible to offer protection that extends beyond the area covered by the helmet."

One idea suggested by Ferdinands is to wear a skull cap, made of composite foam or other substance, reaching beyond the area at the base of the helmet. A study suggests such materials can absorb between 50% and 70% of the impact of a baseball, he adds, saying it would not impede mobility.

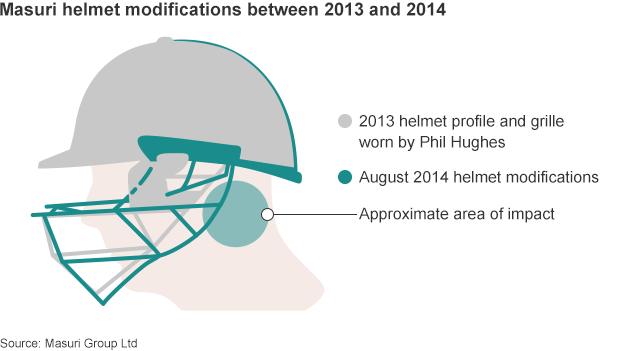

Masuri, the UK company which manufactured Hughes's helmet, says he was not wearing the latest model,, external which offers "extra protection" in the area where he was hit, while still allowing "comfortable movement". It is seeking more video evidence to determine the exact point of impact.

"This is a vulnerable area of the head and neck that helmets cannot fully protect," the company says, "while enabling batsmen to have full and proper movement."

Cricket is one of many sports where helmets are used. In ice hockey, they became compulsory in Sweden in 1963 following a succession of injuries, with other countries doing the same later, including the US from 1979. Face protectors were added in the 1970s and throat protectors in the 1980s.

Helmets are standard in American football, equine events, competitive skiing and many other pastimes involving high speeds or violent bodily contact.

But the International Amateur Boxing Association banned headgear for men's international bouts last year, putting it in line with the professional version of the sport. It said there was evidence to show this could actually cut the number of concussions because it reduced risky behaviour by competitors.

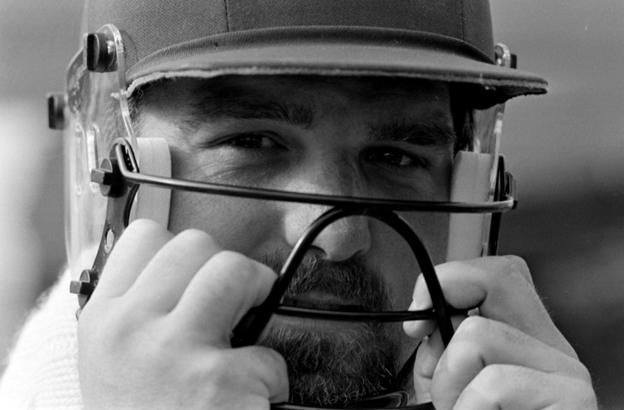

Former England captain Mike Gatting

Cricket has gone the opposite way. "When I first started we didn't have helmets on," said former England captain Mike Gatting, who had his nose broken by a short-pitched delivery from West Indies fast bowler Malcolm Marshall in 1986. "Sadly for Phil, it must have hit one of the very few spots that has done some damage, some severe damage, and it really is just so tragic."

In a study published last year,, external researchers at Loughborough and Cardiff Metropolitan universities analysed 35 videos of first-class cricketers being injured despite wearing helmets.

Most involved being hit on the faceguard or peak, or when the ball got through the gap between them. These mostly caused cuts, fractures and contusions.

But six (17%) of the injuries resulted from the ball hitting the back of the helmet's shell and two (6%) the unprotected neck or occiput (lower left- or right-side region of the back of the skull). The study said impacts in these areas were more likely to result in concussions. This seemed to corroborate findings from US studies into baseball impacts on batters' heads.

Prevention might be improved by "extending the shell of the helmet to cover the entire occipital region", the study recommended.

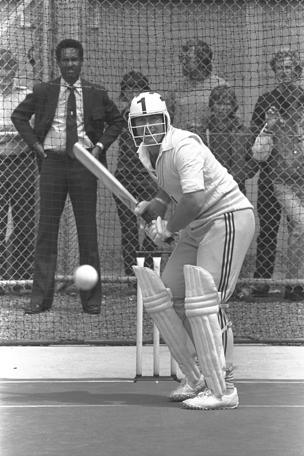

Dennis Amiss (with Garfield Sobers in background) modelling an early cricket helmet, 1978

"We should design helmets as strong as technology allows," says Antonio Belli, professor of trauma neurosurgery at Birmingham University. "But we need to accept that in cricket and other sports that involve hard objects or bodily contact there will always be freak accidents. I would put what happened to Philip Hughes into that category.

"For the number of hours played in cricket, it's actually considered a safe sport in terms of concussion."

But head injury has long been a concern. In the so-called "Bodyline" England v Australia series of 1932, Australia's Bert Oldfield's skull was fractured by a bouncer. This and other incidents prompted an outcry against the use of short-pitched bowling aimed at the body.

The following summer Middlesex and England batsman Patsy Hendren, playing against the West Indies at Lord's, wore a protective cap created by his wife., external Resembling a deerstalker hat, it had three peaks, two of which covered the ears and temples on either side of the head and were lined with sponge rubber.

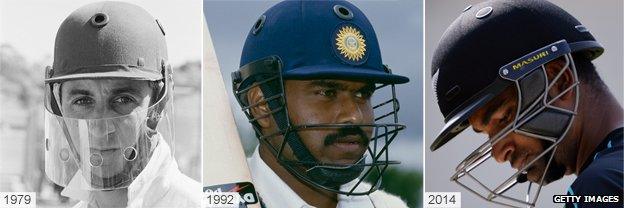

But the use of real cricket helmets has largely evolved over the last 40 years or so.

India's Sunil Gavaskar created his own skull protector. However, he decided not to wear a helmet. "I had a habit of reading before I slept and on most occasions slept while reading," said Gavaskar in 2009., external "My neck muscles got weakened due to this and I feared that my reflexes would slow down while facing a bouncer (if I wore a helmet)."

Helmets "spread like mushrooms after rain" in the late 1970s, according to cricket historian Gideon Haigh, after Australia's David Hookes had his jaw broken by West Indian fast bowler Andy Roberts.

Australian left-hander Graham Yallop was booed when he became the first player to wear a full helmet - an improvised motorcycle helmet, including a plastic visor - in a Test match, in Barbados in 1978. England's Dennis Amiss wore similarly shaped equipment, complete with grille, in World Series Cricket in the same era.

These days top-level players usually wear a helmet when facing fast or medium-pace bowlers. In the UK it is compulsory for cricketers under 18 to use one when batting, whatever the speed of bowling.

Modern helmets are designed to absorb the ball's energy by becoming deformed, or dented, on impact. They contain foam injected in to the cavity between the inner and outer shells to help this.

England all-rounder Stuart Broad edged a ball through the gap between the grille and peak, external of his helmet in a Test match against India earlier this year, injuring his nose.

Ferdinands says this is another area that is being investigated, although there is still a need for batsmen to maintain as much visibility as possibility. "Helmet design is certainly a lot better than it was," he says. "The designers have done a really good job. But this is all a process of evolution. We have to take the next step."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.