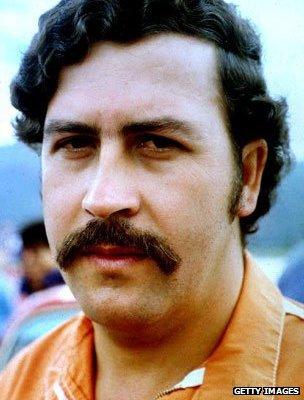

Pablo Escobar: Atoning for the sins of a brother

- Published

It's 21 years since Pablo Escobar was killed in a hail of bullets on a rooftop in Medellin, ending his reign as Colombia's most notorious drug trafficker, responsible for thousands of deaths. Can his crimes ever be forgiven? His sister is trying to atone by leaving notes of apology on the graves of his victims.

"Every day I think of all those people who suffered or are suffering because of my brother - because of the war he waged," says Luz Maria Escobar.

In the 1980s, and up to his death in 1993, Pablo Escobar and his Medellin Cartel inflicted a bloody catalogue of murder and mayhem on Colombia. In 1991, Medellin's homicide rate was a shocking 381 for every 100,000 inhabitants. Some 7,500 people died in the city that year alone.

Escobar targeted politicians, police officers, the security forces, journalists and members of the judiciary in his battle against the state - a war he declared to prevent a law being passed to allow the extradition of drug traffickers from Colombia to the US.

Escobar controlled 80% of the global cocaine trade

Car bombs, kidnap, torture and assassination became part of everyday life. In a failed attempt to kill a presidential candidate, Escobar even brought down an airliner in 1989. The man who would become president in 1990, Cesar Gaviria, was not on board. But more than a hundred people lost their lives in the explosion.

At the height of his power, Pablo Escobar was the seventh richest man on the planet and his cartel controlled 80% of the global cocaine trade. But in 1980, Luz Maria says she knew nothing about her brother's involvement in drug trafficking - until he told the family he had made a will.

"My mother was very upset. She said to him, 'Why are you doing this - are you terminally ill?' And he said, 'I'm in the mafia. Those in the mafia never die of natural causes or illness. Mafiosi die from bullets.' We didn't even know what 'mafia' meant. That night, my mother and I got out a dictionary - but the word wasn't in there."

It was when the Minister of Justice, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, was assassinated on Escobar's orders on 30 April 1984 that reality hit home for his sister.

"That day was awful for me. That's when I knew what he was involved in and what my brother was capable of."

So did she try to persuade her brother to change his life?

"We often went looking for him - I always went with my mother. We spoke to him when there was so much bloodshed, all the massacres… But he was able to convince you the other way. And after my father was kidnapped in 1985, Pablo said to me, 'It's either us or them.' He was carrying a gun for self-defence and to defend the family. But I didn't think at that point it would all go so far - that he would leave such a historic, sad, painful mark on the world."

Now Luz Maria Escobar wants to apologise for the sins of her brother. Last year, on the 20th anniversary of Pablo Escobar's death, she held a Mass at the Catholic church at the Jardines Montesacro cemetery, in Medellin.

Outside the church, around the grave where her brother is buried, she hung notepaper and left pencils. Dozens of Colombians and foreign tourists visit the final resting place of Colombia's most infamous criminal every day, and Luz Maria Escobar asked people to leave her a message of forgiveness.

"Seven or eight people whose families were victims of my brother's violence came," she remembers. "And the nicest thing, something that filled me with happiness, was that people hugged me and told me they weren't full of bitterness towards my brother."

She has also left notes herself at the burial places of Pablo Escobar's victims.

"I just ask for forgiveness," she explains. Once she left a letter on the grave of a mother whose son had been murdered on the orders of her brother.

"I assured her that my heart is here, full of love for all the victims and all the people who were killed."

But what is it exactly that she has on her conscience?

"I don't have anything to repent for in my life like drug trafficking or crime. But your family history is your family history, and it forms part of your heart. And Pablo was my brother…"

A brother's love is what Felipe Mejia misses more than anything. Jaime Hernan Mejia Garcia was 18, just finishing high school, and dreaming of a career in the Colombian Air Force when he was killed in 1989. He has mixed feelings about Luz Maria's notes.

Felipe's brother, Jaime Hernan Mejia Garcia

"I think it's a good thing after all the damage her brother caused. But if one of those notes appeared on my brother's grave, I'd probably throw it in the bin, because just an apology isn't enough. It's a question of justice.

"Some of the guys involved in the killing of my brother are still alive. They have fulfilled lives - they've got children and grandchildren… And I don't have my brother."

Jaime was erroneously connected to the Medellin Cartel's biggest cocaine-trafficking rival in Colombia - the Cali Cartel.

"It was an era in Medellin when anyone identified with the Cali Cartel was simply assassinated. And my whole family was mistakenly linked to them," Felipe remembers.

"For months after my brother was killed, we all slept in the same bedroom with the mattresses on the floor, because my parents said, 'If they want to kill us, they can kill us all together.'"

Felipe and his family did not move away - his parents said they had done nothing to be ashamed of. And the people Felipe believes are connected to his brother's murder stayed too. Felipe still sees them.

"I haven't talked to them for more than 20 years, but my parents greet them cordially. I reproach them for that, and then they start crying," he says.

Luz Maria Escobar cries too. She says although her heart is still full of love for her brother, his legacy is painful for her. But she also defends Pablo Escobar: she claims he has been blamed for things he did not do, and says he did excellent work with the poor.

"Pablo is the only Colombian politician who didn't need to run a political campaign", she says, referring to Escobar's short-lived career as a substitute Congressman in the national parliament. "He won the votes with the help he gave everyone, and the fact he kept his word."

Luis Ospina, whose father was another of Escobar's victims, does not buy it.

Alfonso Ospina, Luis's father

"Pablo Escobar was a psychopath with too much money," he says.

Luis's father, Alfonso Ospina, was a senator from Medellin, and supported extradition of traffickers to the US. On the morning of 15 November 1988 he was kidnapped by members of the Medellin Cartel. He was killed in captivity.

"We even had to pay ransom for the body - that's how bad things were here in Medellin," Luis says with disbelief. "And the contact to do this was a person who had been a friend of my father's, but who worked for Escobar now. We had to ask this man to give us the body. And he asked for money, and said it was for the kidnappers and for all of the logistics that had to be organised. Escobar just bought so many people off."

Pablo Escobar was killed in a police shoot-out on 2 December 1993.

"There was heavy rain, and the river of Medellin was as high as I've ever seen it in my life - it was about to inundate the whole city", remembers Luis Ospina. And I felt this energy… It was a torrent of badness and it was going, it was moving out of the city. That's something I still connect with that day, and the finishing of Escobar."

You can hear The Documentary: The Cult Of Pablo Escobar on the World Service on Tuesday 2 December at 02:32 GMT and 16:32 GMT. You can catch up afterwards on the BBC iPlayer.

More from the Magazine

Situated halfway between the city of Medellin and Bogota, the Colombian capital, Hacienda Napoles was the vast ranch owned by the drugs baron Pablo Escobar. In the early 1980s, after Escobar had become rich but before he had started the campaign of assassinations and bombings that was to almost tear Colombia apart, he built himself a zoo.

He smuggled in elephants, giraffes and other exotic animals, among them four hippos - three females and one male. And with a typically grand gesture, he allowed the public to wander freely around the zoo. A herd of hippos, descended Escobar's animals, has been taking over the countryside near the ranch.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.