WW1: Why was women's football banned in 1921?

- Published

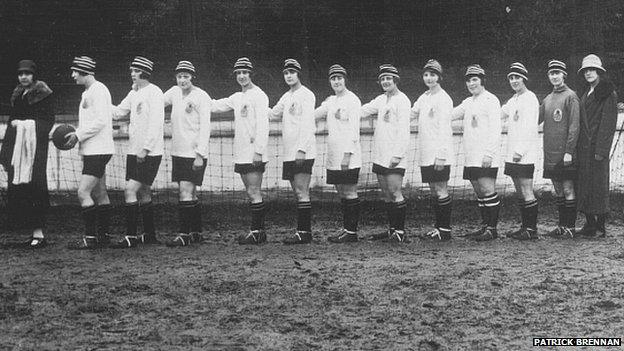

The Dick, Kerr Ladies became international stars

Women's football was huge during World War One, drawing crowds of 53,000 even after the war had ended. So why did it disappear so dramatically, asks Gemma Fay, captain of the Scottish national female football team.

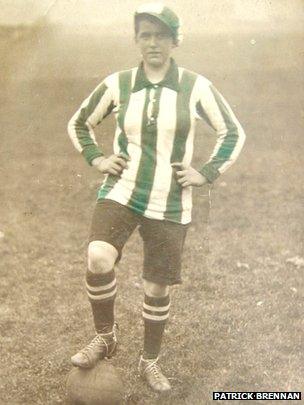

She had a shot so hard she once broke the arm of a professional male goalkeeper. She also earned the distinction of being the first woman to be sent off in an official football match for fighting.

At 6ft tall (1.83m), Lily Parr was remarkable in many ways. She scored more than 1,000 goals during her 31-year-playing career, according to the National Football Museum. Of those, 34 were in her first season when she was aged just 14.

Her team were exceptional too. The Dick, Kerr Ladies were made up of 11 factory workers from Preston. They went on to become international celebrities and the biggest draw in world football. They remain the most successful women's team of all time, says the the museum.

But these were also exceptional times. WW1 was being fought and any man fit enough to play football had been sent to fight on the front line. Back home women not only took on their jobs, they also took their places on the football field.

A Christmas kickabout?

Women's football was already established but up until WW1 it hadn't been well received. This all changed when the Football League suspended all of its matches at the end of the 1914-15 season.

As a generation of young men signed up to serve king and country, so too did the women who were left behind. They answered the call, with hundreds of thousands taking on traditional male roles previously considered too dangerous for women - the most familiar image of these was the munitions factory girl.

Lily Parr started playing football with her brothers

The female workers converged upon the various factories that sprang up across the country, forming strong friendships on the factory floor that spilled over on to the playing fields on their breaks.

Informal kickabouts became a popular pastime for the women and this was not missed by factory management. An activity that was previously considered unsuitable for the delicate female frame was heartily encouraged as good for health, well-being and moral.

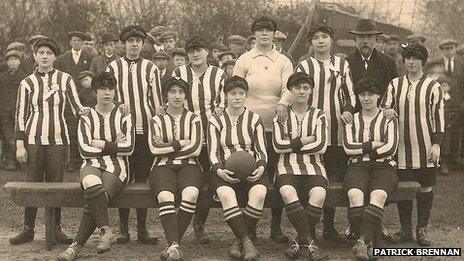

As the war progressed, the women's game became more formalised, with football teams emerging from the munitions factories. Initially, the novelty of women playing football was used to raise money for war charities, with crowds flocking to see the so-called munitionettes take on teams of injured soldiers and women from other factories.

As more teams cropped up, people started to enjoy the matches for the skill and ability of the women, rather than the initial humorous spectacle. Games were still used to raise money for charities.

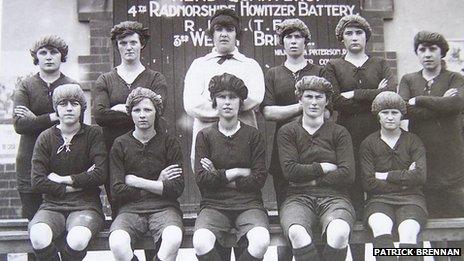

The Munitionettes' Cup was established in August 1917, with the first winners Blyth Spartans beating Bolckow Vaughan of Middlesbrough 5-0. Star striker Bella Reay scored a hat-trick to add to her 130 other goals that season.

Their love of the game was such that on one occasion Blyth winger Jennie Morgan is said to have gone straight from her wedding to play in a match - she scored twice.

Football at home during WW1

The most famous of these teams was Dick, Kerr Ladies FC from Preston. Founded in 1917, their first match drew a crowd of 10,000 people. By 1920, a Boxing Day match against St Helen's Ladies was watched by 53,000 spectators at Goodison Park, with another 14,000 locked outside the ground trying to get in.

With the war now over, a nation devastated by the loss of so many attempted to put itself back together. One by one, the factories closed and women who had been galvanised and liberated during wartime, found themselves being quietly shunted back into domestic life, returned to their "right and proper place" in society.

Football was no longer a health benefit - it was now seen by top physicians, such as Dr Mary Scharlieb of Harley Street, as the "most unsuitable game, too much for a woman's physical frame".

Bella Reay was an international star

Despite these warnings, the Dick, Kerr Ladies were still the leading team in Britain. Their popularity reached its height in 1921, with big crowds wanting to see them play. However, this "golden era" of women's football was to be short-lived.

On 5 December 1921 the FA cited strong opinions about football's unsuitability for females. It called on clubs belonging to the associations "to refuse the use of their grounds for such matches". The ban changed the course of the women's game forever.

Despite this a few female teams continued for a while. In 1937 the Dick, Kerr Ladies played Edinburgh City Girls in the Championship of Great Britain and the World, winning 5-1. Lily Parr became one of the greatest scorers in English history, netting more than 1,000 goals during a 31-year career. However, the women's game soon became overshadowed by the return and growth of the male game.

In 1971 the FA finally lifted the ban on women's football. In the same year UEFA recommended the women's game should be taken under the control of the national associations in each country. This move signalled the start of a female football revival, not only in Britain but across Europe and the rest of the world.

The first official European Championship was held in Sweden in 1984 with the inaugural World Cup taking place in 1991. Fast forward to now and women's football is a global phenomenon. At the 2012 Olympic Final at Wembley Stadium between the USA and Japan, a record-breaking crowd of over 83,000 was in attendance.

The astounding fact is that only now, nearly 100 years later, are women attracting the crowds and attention experienced by their predecessors. These pioneering women not only managed to achieve phenomenal success and recognition, but they did it at a time when it would have seemed nigh on impossible. They defied society, changed the mindset of a nation and took women's football to unprecedented new heights, all within a couple of years.

During WW1 female matches raised money for charities

I have huge adoration and respect for the footballing women of WW1, but also a pang of jealousy and frustration. Having been involved in women's football in this country for nearly 18 years, I have never experienced the level of public interest and support they did. The stories of their struggles in the post-war era, however, bears a resemblance to my early years in the sport. There were frustrations which can unfortunately still be felt in some quarters today.

With the England women's team securing its biggest crowd at Wembley of 40,181 in a recent friendly against Germany, it has taken the current generation nearly 43 years to achieve something remotely close to their success.

And what of Lily Parr? Her achievements were finally recognised in 2002, when she became the first woman to inducted into the Football Hall of Fame at the National Football Museum in Preston, 24 years after her death.

Discover more about the World War One Centenary.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.