The town with three Christmas Days

- Published

Christmas comes but once a year - unless you live in Bethlehem, where three different Christian denominations celebrate on three different days.

There are no calls of "legs eleven" or "two fat ladies" at the Arab Women's Union bingo in Bethlehem.

And there's another big difference from your standard British game. Instead of cash, the prizes are household items: washing powder, toilet rolls or, if you're lucky, an electric blanket.

Bingo is always popular with housewives here but the idea of the union's weekly gathering is to raise funds for charity.

In the run-up to Christmas, it organises a party for needy children. Dozens of local kids are entertained with clowns, fed lunch and given goodies to take home.

Christian members of the women's union feel a special responsibility for keeping alive the Christmas message of compassion and hope.

"Christmas is our national feast and the feast of our city," says president and great-grandmother, Virginique Canawati.

"It's not Christmas if you're happy at home with your family and you have a neighbour with nothing," adds the bingo caller, Susie Nasr.

"There's a lot of poverty in Bethlehem. We have the highest unemployment in the West Bank and people have to think about every penny they spend," she adds.

After a game of bingo earlier this month, I proudly displayed my winnings - a large bottle of fabric conditioner and a packet of wet wipes.

Then as we polished off some tasty thyme and cheese pastries, the women told me about the delicious meals they had planned for Christmas dinner.

There's not really a market for turkey and all the trimmings here, although one year I did surprise my visiting parents - who are used to oven-ready products - by returning from the butcher's with a warm, freshly killed bird in a plastic bag.

The preference of Christians in the Holy Land tends to be Arabic salads followed by a main course - perhaps lamb stuffed with rice, or maashi - stuffed vine leaves, aubergines and courgettes.

While there's an emphasis on having new clothes for the feast, gift giving is far less excessive than you typically see in Western countries.

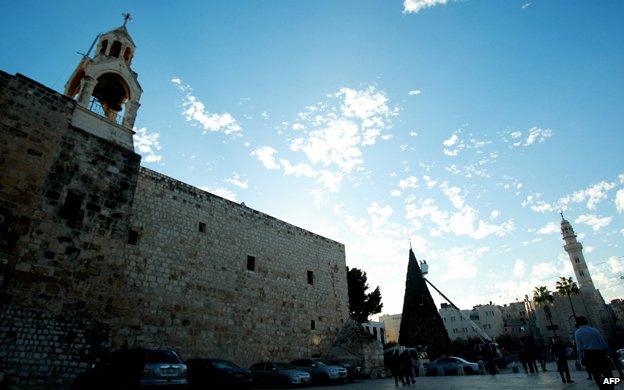

Decorating the Christmas tree in Manger Square

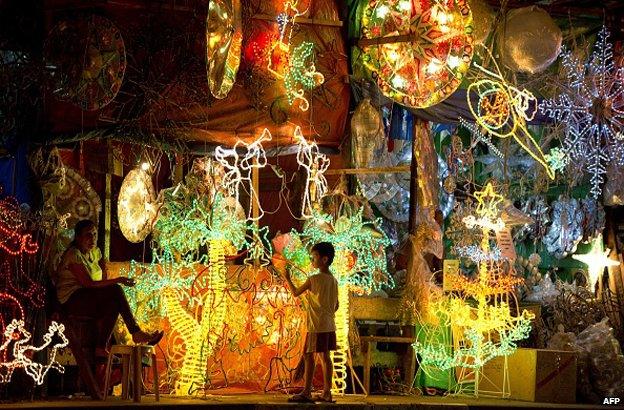

Christmas decorations on sale in Bethlehem

And the celebrations go on for longer than we're used to. Indeed, rather than having one Christmas Day, three are marked in Bethlehem.

The Catholics lead processions along the traditional pilgrimage route from Jerusalem to the Nativity Church ahead of their Christmas on 25 December.

But now attention switches to the Greek Orthodox, who make up the majority of Palestinian Christians. Their Christmas Day falls on 7 January.

The 13 day difference is explained by calendars. While the Latin church switched to the Gregorian calendar, devised by Pope Gregory in the 16th Century, the Eastern Orthodox churches still use the older, Julian calendar - created during the reign of Julius Caesar in 45 BC.

What makes the situation in the Holy Land really unusual is that Armenians here wait even longer for Christmas. Their parade isn't until 18 January.

On each Christmas Eve, Bethlehem gives a warm welcome to church patriarchs and priests when they enter Manger Square.

And as waiting crowds of the faithful munch chocolate Santas and sip at sahlab - a hot Ottoman-era drink made from orchids - it's the marching bands that keep them entertained.

The Grotto at Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem where Christians believe Jesus was born

For weeks now in Beit Jala, the town next to Bethlehem where I live, there's been the constant din of drums and bagpipes - as the scout troops practise their festive routines.

Scouting was introduced to Palestine in British Mandate times - from 1920 to 1948 - and it remains hugely popular with boys and girls.

The head of the Arab Orthodox Scout Group, Khaled Qassis, looks more than a little stressed as he organises a Christmas bazaar and street clean-ups while the pipers play on.

But he can't disguise his pride at his scouts' place in the Christmas line-ups.

"As scouts, the last thing we're interested in is showing off," he tells me. "But we are very famous for playing well."

Many Palestinian Christians see themselves as custodians of Christmas and its colourful traditions.

The dwindling number of Christians in the Holy Land adds a sense of urgency to their celebrations. Nowadays many young people in the West Bank choose to emigrate because of the difficult economic and social conditions created by Israel's occupation.

In the quiet of Beit Jala's Virgin Mary church, where the air's thick with incense, Father George reflects that this time of year carries spiritual and political significance.

"When we celebrate we show the world that Bethlehem's a peaceful, safe city," he says.

"This is the birthplace of Christ and we're the oldest congregation in the world. If we don't light our trees and hang decorations here, then we'll die out."

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: at weekends - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox