Abdi and his Golden Ticket to the US

- Published

Abdi Nor Iftin fled Somalia only to land in one of Kenya's worst slums. When he won the US green card lottery his problems seemed to be solved - but it turned out to be the start of a whole new struggle.

In Somali slang, there is a special word for the daydream of starting a new life in a far-off land: it's known as a bofis. And for millions of refugees across Africa, there is one bofis that obsesses people above all - the idea of moving to the West, and in particular to the US.

For most, it remains an impossible dream. But there is one legal way in which even those without wealth or connections can do it - getting a lucky break in the US Diversity Visa Program, better known as the green card lottery. In 2013, nearly eight million people applied for just 50,000 winning tickets, which means that for every 1,000 applicants only six won the chance of a new life.

For the past year, I've followed the story of one of the winners - a young Somali refugee called Abdi Nor Iftin, living in the Eastleigh district of the Kenyan capital Nairobi. Known as Little Mogadishu, it's one of the country's toughest slums. And one thing I discovered is that becoming an American is not easy, even for those who do have a winning ticket.

There is no denying that there is something a little strange about the Diversity Visa Program. At a time when immigration to most Western countries is becoming ever more restricted, the US government still gives away 50,000 permanent resident visas each year to people chosen at random from across the world. Entries from most developing countries are permitted, and only a high school education, or a few years of work experience, are required. The stuff of a true bofis.

When I first contacted Abdi he had been living in Little Mogadishu for some time. He and all his friends had applied for the lottery together as a group, at a local internet cafe, but Abdi was the only one to be picked by the lottery computer. "We all cheered! We picked him up!" remembers Yunus, one of Abdi's best friends. "Everybody was holding him, we were shouting, 'You won it, you won it! You are going to America!'"

A remarkable stroke of good fortune? No, says Abdi, it was his fate.

"This was not just luck. My whole life I have been in love with America - the best country in the world, the dreamland, the land of opportunity," he says. "Ask anyone what they called me when I was a kid in Mogadishu and they will tell you. My nickname then was 'Mr America', or 'Abdi America'. Everyone used to joke about it."

Abdi spent most of his childhood in Mogadishu.

He dodged the bullets of Somalia's civil war, and survived famines. He coped with the suffering around him by watching Hollywood films, and using them to teach himself fluent English. "I was crazy about movies - watching Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Willis," Abdi remembers. "I liked the way they sounded; the way they talked. I wasn't learning how to speak English like that, with that American accent, from my school."

At a local cinema which showed Hollywood movies without subtitles, Abdi became the unofficial translator, explaining the plot and the dialogue to the rest of the audience as each film was screened. "People would listen to me, and wait for me to tell them what was happening," he says.

Some of the things he saw in those films fascinated him. Snow for example. And doughnuts. "In movies about the police they always talk about doughnuts!" I asked him what he thought a doughnut was. "I think it's something like a circle with a hole. With some juice in it maybe? It just looks tasty- it gets my saliva going! I want to try that thing!" he told me.

But being well known for a love of America and American culture can also be dangerous. As the Islamist al-Shabab rebel group took control of much of Somalia, Abdi was forced to follow his brother Hassan into exile in Nairobi.

By the time he applied for the lottery, he was considering any way to try and reach the West. Several of Abdi's close friends had tried to make it to Europe by boat from North Africa. A few had made it. Others had drowned in the attempt. Even more were planning to try it in the future.

Unfortunately for Abdi, being selected as a winner in the lottery is very far from being a guarantee of reaching the United States. Each person selected also needs to present lots of papers and pass a final interview at a US embassy. On that day, each applicant's entire future is decided.

A majority of applicants never successfully complete this process. In fact, the system is deliberately designed this way. The Diversity Visa Program has to distribute 50,000 visas each year, but to take account of interview failures and substandard applications, the number of randomly chosen applicants like Abdi is more than double that. In 2013, when he applied, approximately 105,000 hopeful applicants were picked by the system. Once the full quota of visas has been assigned, all remaining applicants are automatically refused.

The odds of success for Abdi were soon to get even worse. While he was waiting for his embassy interview, al-Shabab launched the horrific Westgate Shopping Mall attack in Nairobi, killing and injuring dozens of innocent people. Further terrorist attacks followed, and the Kenyan authorities responded with a huge police crackdown on Somalis in Eastleigh.

Although al-Shabab supporters were the official target, it felt as though every Somali refugee was at risk of arrest, deportation or internment in camps. Hassan, Abdi's older brother, was particularly concerned for Abdi at that time. "Being a refugee became a crime," he told me. "We would hide in our houses. And you could hear screams, children crying, women being hauled away on trucks. Being in that room, listening, waiting for someone to take us both away - can you imagine how that feels?"

For Abdi, it felt as though his entire dream of a better life in the states was being snatched away just when it was within his grasp. Any arrest, however unjustified, could have led to deportation or internment, making it impossible for him to attend his US embassy interview.

During this period, Abdi and Hassan went into hiding, but we continued speaking regularly on the phone and via Skype, recording our conversations. As a journalist working safely and comfortably in London this was often a strange and humbling experience.

On one occasion I spoke to him while the police were still in his building, having extorted a bribe from the neighbours. I would finish my day at the office, and call up Abdi to ask him how his had been. Abdi described the situation, then politely asked me how my work was going and how my family were. Fortunately, the police left without further incident.

Worse was to come. As the police operation went on, week after week, Abdi and Hassan began running short on food. So many Somalis in the area had either been arrested or fled that most shops in Little Mogadishu had been abandoned. Eventually, when the two brothers were down to just bread and tea, Abdi took a huge risk, and ventured out to central Nairobi, where life continued as normal. To his huge relief, he was able to make it back to their room safely carrying a few vegetables and tinned foods.

Residents of Eastleigh watch as a suspected roadside bomb is defused nearby

But another of our conversations took place a few hours after Abdi narrowly escaped a Kenyan vigilante mob armed with rocks and machetes. He had managed to dive through the gates of a local mosque, but another Somali man on the street had not been so lucky.

Had Abdi expected to die at that time, I asked? "I did, yeah. There was one moment, when I was thinking, 'OK, this is the end of it, man. They were coming…"'

The key documents required for a green card interview include a birth certificate, proof of education or work experience and a police clearance document (essentially a criminal records check). It was the last of these that was a particular challenge for Abdi. He had no criminal record with the authorities, but in order to prove this in writing he had to apply to the Kenyan police headquarters directly. Exactly the place in Nairobi where Somali refugees were least welcome.

Police arrest a young man in Eastleigh for lacking ID documents, in April 2014

The strain began to tell. In one conversation around this time, Abdi told me he had been watching National Geographic documentaries on YouTube - it is a feature of urban refugee life that wi-fi connections can persist even when food and water runs low. "Have you ever seen wildebeest?" he asked me. "Every year these wildebeest have to cross this big river, and the river is infested with crocodiles. So I think that these wildebeest are risk-takers. They have to cross to the other side or die trying. What I am saying is: we are now the wildebeest."

And then, unexpectedly, a further stroke of luck - or fate. After several terrifying visits to the police station, Abdi was told that yes, he would be issued with a formal police clearance letter, confirming his status as a valid applicant for a green card. That evening he told me he could not stop staring at his ink stained fingertips, still marked from the police fingerprint pad. He did not even want to wash them, he said, just to keep the ink there a little longer. Abdi was finally ready for his interview.

A Somali man in Eastleigh is taken away for questioning in April 2014

The evening before the interview, I wished Abdi good luck and made arrangements for us to speak as soon as he left the US embassy. Everyone who knew Abdi was quietly confident. With his love for America, his fluent English and his dreams of becoming a journalist in the US, he seemed like the ideal candidate. Abdi said that he could not wait to tell his parents and his friends that he had a green card.

Early on the the morning of the interview, I received a text message from Abdi while I was brushing my teeth. It was not what I was expecting. The interview had been a failure and his application had been rejected: "Today is my worst day on earth," he wrote.

It emerged that Abdi's police clearance letter was in order, but one of his university transcripts was a copy rather than a signed original. Any paperwork errors can be the kiss of death when so many candidates are applying. Hassan and all of Abdi's friends were heartbroken. Many of them had seen him as a role model for how to escape the grind of refugee life.

But Abdi had been overhasty in concluding that it was all over. In fact he had not been refused outright. Although it made his application less likely to succeed, there was scope for him to resubmit the papers he was missing, and ask for his application to be reviewed. He got the necessary document from the university in Nairobi and rushed round getting officials to sign it.

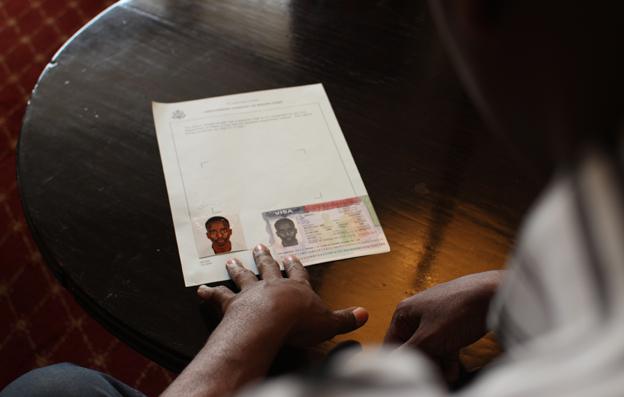

A few days later, the result came in. Abdi had been finally, accepted on to the Diversity Visa Program. As a refugee from a failed state, he had no passport, so the visa was printed loose-leaf for Abdi to take to the airport.

Abdi America is now living legally and with his green card in snowbound Maine in the US. So far life in the States has lived up to his bofis. He has found work with an insulation installation company, and has sent his first instalment of cash home to his mother in Mogadishu. The appeal of snow has worn off, but his favourite doughnut at Dunkin Donuts is the classic glazed kind (without "fruit juice").

His diet is changing in other ways. "You know what I just love more than anything?" he asked me recently. "Ice cream! People say it will make me fat, but I want to be fat. I've been skinny my whole life, and now I don't care, Leo, I don't care!"

You can listen to Abdi and the Golden Ticket on BBC Radio 4's Crossing Continents on 29 December at 20:30 GMT or catch up afterwards on iPlayer. The programme ran on the BBC World Service's Assignment programme on Christmas Day, and can be heard on the Assignment website.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox