The big ideas of 2014: Part I

- Published

A slew of big ideas were debated in 2014. Uber took on the taxi market, Ukip achieved unprecedented success and Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century was a bestseller.

All of these ideas - ridesharing apps, the UK leaving the EU and theory of capital generating inequality - made their debut earlier, but the past 12 months have seen them truly flare. Here are the first three of the dozen ideas. Part II - with the second three - is here. Part three and four will follow later.

1. Uber and the battle over taxi apps

In the Western world, largely dominated as it is by free-market principles, the taxi sector stands out as one of the more heavily regulated areas of economic activity.

In New York, taxi medallions - which allow the owner to run a yellow taxi - change hands for huge sums. In London, only black cabs can use a meter. In Paris the number of taxi licences being given out has failed to keep up with demand, external - at the behest of the unions, critics say.

Defenders of the status quo say it protects them from unfair competition and protects customers from danger - the drivers are registered, reliable and safe. To others it smacks of a closed shop which leads to very high prices in some cities.

In 2014 a major player - Uber - has intensified its attack, external on the status quo. The firm is rumoured to be bringing in gross revenues of nearly $1bn a month. There are several others, including Lyft and GetTaxi.

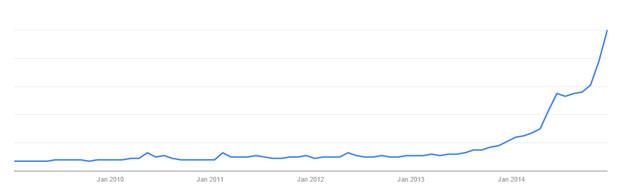

Google trends: interest in the term 'uber' since company launch

Uber's management has made no bones about its desire to undercut black cabs and yellow taxis and their equivalents around the world. Uber is the middleman. Its app - in many countries - enables private individuals to use their cars as taxis by putting the driver in touch with people wanting a ride. In other countries the app offers access to licensed drivers but at a price that is often much lower than conventional taxi and minicab services.

Customers register and download an app, entering their credit card details. When they are looking for a ride, the phone picks up their location and tells them where the nearest cars are and how long it will take. The driver receives 80% of the fare, Uber 20%.

The San Francisco-based company was set up in 2009 and began expanding to many major global cities in 2012. It now operates in around 230 cities in nearly 50 countries. It has been valued at more than $40bn. But 2014 was the year it collided head on with the taxi drivers.

Spain, India and Thailand prohibited Uber from operating. The Netherlands has banned Uber's cheaper UberPop service. The authorities in Portland, Oregon, have brought a lawsuit against Uber. They complain that Uber does not guarantee disabled access, its drivers do not have proper insurance and that there is no maximum price cap.

Uber operates in London, although there are legal cases pending. The key conflict is over whether the Uber app amounts to a taxi meter. This would be illegal as only black cabs are allowed them. Transport for London has allowed Uber to operate but asked the High Court to rule. The case cannot go ahead until a prosecution brought by the London Taxi Drivers Association in the Magistrates Court has been heard.

Uber has suffered a series of PR disasters. There have been questions over tax - the app's Dutch operating firm, Uber BV, does not pay tax in the UK, for instance. There has also been controversy about the company's attitude to journalists after Emil Michael, senior vice president of Uber, was heard suggesting the company dig up embarrassing details from the private lives of journalists who are negative in their coverage. Others worry about how the company deals with customer's data.

The safety issue is a significant one for Uber. There was an arrest in India of an Uber driver for allegedly raping a passenger. There have been several allegations of rape and sexual assault, external in the US. An Uber driver in Philadelphia is to stand trial for punching another driver, external. In London, an Uber driver was sacked, external after propositioning a customer.

But the company says it is safe. In the US, Uber employs "a three-step criminal background screening with county, federal and multi-state checks that go back as far as the law allows". In the UK, a Transport for London spokesman points out that Uber drivers undergo the same Disclosure and Barring Service checks that minicab and black cab drivers undergo.

But the head of the London Taxi Drivers' Association has said the company's use, external of recent immigrants as drivers means the checks are no guarantee of safety.

Supporters say the central issue of competition driving down price is important. "People may say they are outraged but if the service on offer is cheap and convenient, it will be hard to resist," the Economist wrote. The taxi trade is in urgent need of a shake-up, it argued. "Taxi markets often end up suspiciously clubby, with cabs in short supply and fat profits for the vehicle owners." It noted that in New York a pair of taxi medallions - for driving a yellow cab - sold in 2013 for $2.5m while in London "the knowledge", which it argues has been made redundant by GPS navigation, can take four years to complete.

Ravinder Johal, secretary of the Taxi Owners' Association in Birmingham, says Uber is competing unfairly. Their cars do not have to be accessible to wheelchair users for one thing. "We take 300-400 wheelchairs every week. What they are doing is trying to cream off easy work - a single person going A to B."

2. Thomas Piketty and increasing inequality

No-one saw it coming. It's 577 pages long. The only photo shows its author, a French academic, in front of a whiteboard covered in algebra. It has chapter headings like The Capital/Income Ratio over the Long Run. The pages are littered with graphs and tables. Yet Thomas Piketty's book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, got to the top of the bestseller lists in 2014. It has shifted about half a million copies in English. Piketty has become an unlikely star.

"When the movie is made about the fall of Western capitalism, Thomas Piketty will be played by Colin Firth," wrote the Guardian. Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman called it "the most important economics book of the year - and maybe of the decade". For New York Magazine, he was a "rockstar economist", while the New Republic compared his arrival stateside to that of the Beatles 50 years ago, external.

The book came out in 2013 in France to polite but muted acclaim. But the English translation published in April this year met with a very different reaction.

Its main thrust is that over time, the value of capital has increased more quickly than income. If you are rich - owning assets like shares and property - your wealth will have increased proportionally more than someone reliant on earning a wage. The thesis was backed by a mass of historical data.

Its timing, with the scars of the banking crisis still fresh, was impeccable. The Occupy Movement has focused on the richest 1% - who Piketty says own about 25% of the wealth - and the question of whether big firms like Apple, Facebook, Google, and Starbucks are paying their taxes. Piketty's trawl through the data leads to the following conclusion: "The general evolution is clear - bubbles aside, what we are witnessing is a strong comeback of private capital in the rich countries since 1970, or, to put it another way, the emergence of a new patrimonial capitalism."

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Piketty analyses centuries of economic data and concludes that not only is inequality increasing, it's hard-wired into capitalism

Things get more equal when wars destroy inherited wealth

The return on capital - assets and wealth - is greater than growth in economy overall

The rich are destined to get richer, everyone else stays more or less the same

Advocates new tax rate for the rich

Some of the data sets were challenged by the Financial Times, external. The newspaper's Chris Giles said Piketty "appears to have got his sums wrong" and that the errors "skew his findings". Piketty - who had already made the data public - made a detailed response. The Spectator attacked his work as "shaky", external.

There were many supporters who insisted the sums did add up, external.

"The strength of his thesis is that it is founded on evidence rather than ideology," wrote Oliver Kamm in the Times. "He is able to point convincingly to a recent reversal of historical trends, so that the share of national income taken by the owners of capital has expanded over the past generation."

Under the headline "My contender for the stupid socialist award", another Times writer Danny Finkelstein objected, external to Piketty's policy prescriptions, which include a global wealth tax. "The proposals that Piketty makes may not be on the epic scale of Mobutu, but they are not obviously more practical. Or desirable."

Bill Gates applauded Piketty's scholarship but disputed his central theory: "About half the people on the [Forbes 400] list are entrepreneurs whose companies did very well (thanks to hard work as well as a lot of luck). Contrary to Piketty's rentier hypothesis, I don't see anyone on the list whose ancestors bought a great parcel of land in 1780 and have been accumulating family wealth by collecting rents ever since."

Others noted the quieter reception in France for Piketty's book might lie in the fact that he was closely identified with Francois Hollande's swiftly abandoned 75% tax rate. That and the fact that decrying capitalism is nothing new in France, external.

"The reaction to Piketty is an amazing cultural phenomenon," New York Times columnist David Brooks noted, external. The book, he argued, was the perfect text for middle class liberals rich in cultural capital unable to compete financially with hedge fund managers or private equity people. "It says more about class rivalry within the educated classes than it does about how to really expand opportunity."

But what is not in doubt is that Piketty's data on inequality has pushed it back to the heart of the political debate.

3. The drive to get the UK out of the EU, and the rise of Ukip

There have been many Eurosceptics, inside and outside Westminster, who have campaigned for years to get the UK out of the EU. But 2014 represented a significant intensification. In 2013 Prime Minister David Cameron had announced there would be a referendum on whether to stay in the EU if the Conservative Party won the 2015 election. But 2014 has seen significant successes for Ukip. The party won two by-elections to get its first MPs.

And for the first time in modern history a British election was won by neither Labour or the Conservatives. Ukip triumphed in May's European elections with 27.5% of the vote.

David Cameron tried and failed to prevent Jean-Claude Juncker becoming European Commission president. The prime minister said Europe's decision to back Juncker would make it harder for the UK to remain in the EU. There was a supplementary budget bill of £1.7bn, which appeared to take the prime minister by surprise.

But the success of Ukip is really part of the rise of immigration as a political issue, says Times columnist Tim Montgomerie. It shows how impotent the UK currently is on immigration, he believes. "Many put the rise of Ukip down to immigration and the idea that the only way you can control immigration is if you leave the European Union."

The UK has had sustained high immigration for a decade. There are concerns among many voters that the numbers of workers coming in from eastern European countries - where pay is generally lower - has depressed wages in the UK. The government made it a pledge at the last election to reduce overall levels of net migration below 100,000. The government has now accepted that target will not be met. Indeed in the year to June 2014, 260,000 more people arrived in the UK than left. The UK has strict rules on foreign nationals from outside the EU settling in the UK. But the EU has a policy of freedom of movement, meaning it is very difficult to limit migration from other member states. The government is now proposing a four-year wait before newly arrived migrants can claim certain benefits.

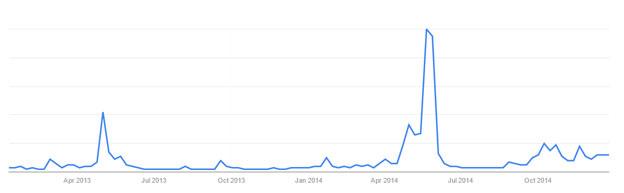

Google trends: interest in the term 'Ukip' since January 2013

The debate has created rifts with some of the UK's partners. In November, German news magazine Der Spiegel reported that Chancellor Angela Merkel had for the first time conceded - in private - that the UK might leave the EU.

The economic merits of EU membership have also been questioned. In April the Institute for Economic Affairs, a right-leaning think-tank, awarded a prize of €100,000 (£78,000) for the most persuasive plan for a British withdrawal from the European Union. The winning proposal reckoned that "Brexit" - British exit - would boost the economy by £1.3bn, external.

It's no longer just Ukip calling for Brexit, says Montgomerie. There's now "a pretty broad spectrum", he says pointing to entrepreneur Sir James Dyson, senior Conservatives Lord Lawson, Lord Lamont, and business leader Lord Digby Jones. There could still be a shift in favour of EU membership, he believes. "If David Cameron can convince people that he's got meaningful renegotiation (on EU treaties) then I think support for leaving will drop like a stone." But if the EU does not give ground or looks like it's "snubbing" the UK then "all bets are off".

But Timothy Garton Ash, professor of European Studies at Oxford University, says it seems unlikely the fundamental principles of the EU's free market will be altered. "You can't have the EU without freedom of movement in people and capital." Things can change a lot before a referendum in 2017, he believes. "There are many moving parts." There's the election - first whether Cameron is re-elected, second how Ukip fare. And then how the economy in the UK and EU perform. British people are worried about immigration and the workings of the EU, he says. "But I don't believe there's been a fundamental shift away from Europe in a broad sense."

Part II will be published on 30 December.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox