Why did my grandfather translate Mein Kampf?

- Published

Whenever I tell anyone that my Irish grandfather translated Hitler's Mein Kampf, the first question tends to be, "Why did he do that?" Quickly followed by, "Was he a Nazi?"

Simply answered, No he wasn't a Nazi (more on that later) and why not translate it? He was a journalist and translator based in Berlin in the 1930s and that's how he earned his money. And surely it was important for people to know what Europe's "Great Dictator" (apologies to Charlie Chaplin) was about?

Certainly my grandfather and many other non-Nazis thought so at the time. Let's also not forget this was before Hitler became the most notorious figure of evil in history.

Hitler made a fortune from Mein Kampf. Not only did he excuse himself from paying tax, after he became Chancellor the German state bought millions of copies which were famously handed out to newly married couples. It's estimated that 12 million copies were sold in Germany alone.

The story of my grandfather's translation - the first unabridged version in English, which was eventually published in London in 1939 - is an intriguing one. It involves worries about copyright, sneaking back into Nazi Germany to rescue manuscripts and a Soviet spy.

My grandfather, Dr James Murphy, lived in Berlin from 1929, before the Nazis came to power. He set up a highbrow magazine called The International Forum which chiefly contained translations of interviews he'd done with eminent people, including Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann. However, as the Depression worsened, he was forced to move back to the UK.

Dr James Murphy, journalist, translator and polymath

While there he wrote a short book, Adolf Hitler: the Drama of his Career, which sought to explain why so many Germans were attracted to the Nazi cause.

My grandfather returned to Berlin in 1934, where he ridiculed the garbled translations of Nazi policy statements. He was especially critical of an abridged version of Mein Kampf - about a third of the length of the original two-volume work - which had been published in English in 1933. Towards the end of 1936, the Nazis asked James to start work on a full translation of Mein Kampf. It's not clear why. Perhaps Berlin's Propaganda Ministry wanted to have an English version which it could release when it felt the time was right.

But at some point during 1937 the Nazis changed their minds. The Propaganda Ministry sequestered all completed copies of the Murphy manuscript. He returned to England in September 1938, where he quickly found British publishers keen to print his full translation - but they were worried that the Nazi publishing house, Eher Verlag, hadn't given him the copyright. And anyway, he had left his completed work behind in Germany.

Just as he was about to set off for Berlin to sort all this out, he received a message through the German embassy in London, saying he wasn't welcome. James was distraught. A natural spendthrift, he'd run out of money, and had great hopes for the English publication. But at this point, his wife - my grandmother - said she would go.

"They won't notice me," she said, according to my father, Patrick Murphy.

"So she went back into Germany and made an appointment with a Nazi official we knew in the Propaganda Ministry, a man called Seyferth," my father says.

Unfortunately Mary Murphy had chosen a bad day, 10 November 1938 - the morning after Kristallnacht, when Jewish shops and businesses were attacked by Nazi thugs. Nevertheless, her meeting with Seyferth went ahead.

"You know a group of Americans is working on a translation right now, so you can't stop it coming out," she told him. "You know my husband has done an accurate and fair translation - an excellent translation… so why not hand over the manuscript?"

Seyferth refused. "I have a wife and two daughters. Do you want me put up against a brick wall and shot?" he said.

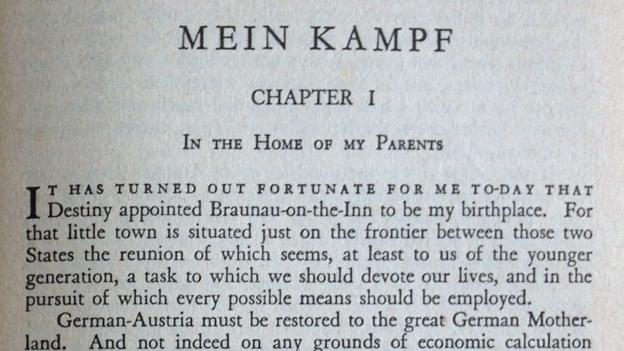

Then Mary remembered that she had previously handed a carbon copy of a first draft of her husband's translation to one of his secretaries, an English woman called Daphne French. She tracked her down in Berlin and, fortunately, Daphne still had the copy. Mary brought it back to London. With an American translation about to be published in the US, the race was on to get my grandfather's translation out as quickly as possible. In March 1939, Hurst and Blackett/Hutchinson published the first British unexpurgated version of Mein Kampf.

Hurst and Blackett's 1939 edition of Mein Kampf

By August 32,000 copies had been sold and they continued to be printed until the presses were destroyed - by a German air raid - in 1942. A new American version subsequently became the standard translation. One copyright expert, who has written about Mein Kampf, estimates that between 150,000 to 200,000 copies of the Murphy edition were eventually sold.

My grandfather, however, did not receive royalty payments. Hutchinson argued that he had already been paid by the German government and that the full copyright hadn't been secured, so they could still be sued by Eher Verlag. An official letter from Germany, which turned out to be a diatribe against James Murphy, made clear Berlin disapproved of his translation. But the Germans didn't take any action. Eher Verlag even requested complimentary copies and royalty payments. They didn't receive them.

The Murphy edition is now out of print but copies are scattered across the world and it can be found online, external.

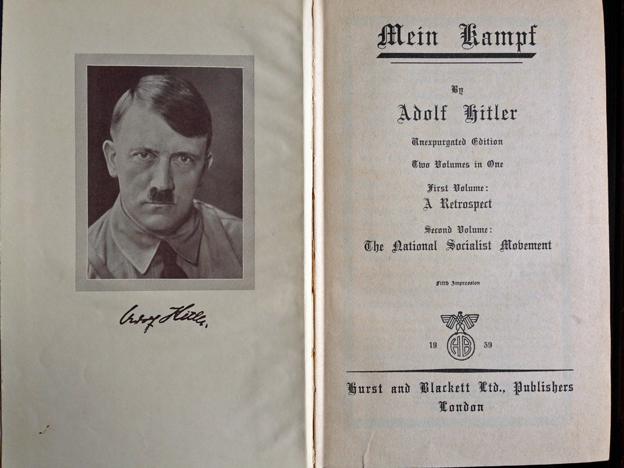

The Wiener Library in London, which has a unique collection of material on the Holocaust and genocide, has a remarkable copy of Murphy's Mein Kampf in its vaults. Inside the flyleaf there's a photograph of Hitler, and a group of smiling people, in Berchtesgarden, in the Bavarian Alps. A note, written in pencil, explains that Hitler came into the village and signed copies of Mein Kampf. His signature is there, in pencil.

The book, bought in 1939 in the UK, was seemingly taken by British admirers as they visited the Fuehrer's Alpine retreat. The photograph has somewhat comical annotations in the form of three pencilled arrows. By the top arrow is the handwritten note, "M. Bormann?" The next one down simply says, "Hitler". And the last arrow, pointing to a young woman in a white dress in front of Hitler, says: "Karen".

An edition of Murphy's translation of Mein Kampf, signed by Hitler

"Karen must have been the owner of the book or related to the owner of the book," says Ben Barkow, the Director of the Wiener Library. "But it's always slightly chilling to hold the book in one's hand, knowing of course that he held it in his hand when he autographed it."

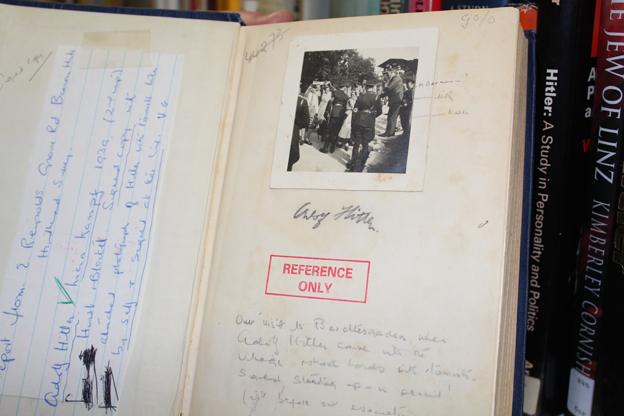

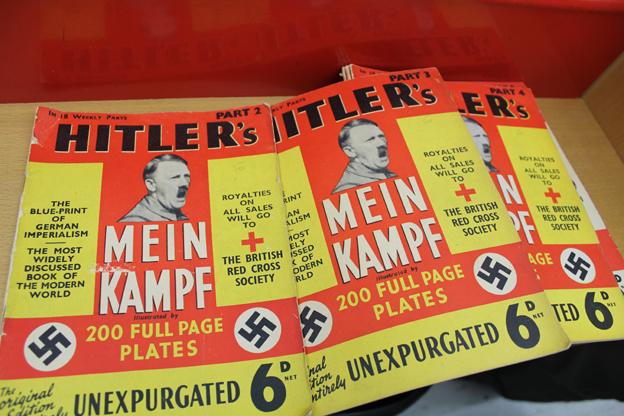

And if that wasn't strange enough, Barkow, then produces a Murphy edition which Hutchinson brought out in 18 weekly parts. Bright yellow and red, each part sold for sixpence. What's extraordinary, though, is what it says down one side of the cover: "Royalties on all sales will go to the British Red Cross Society." On the other side of the cover: "The blue-print of German imperialism. The most widely discussed book of the modern world."

Mein Kampf today

As Hitler's official home was Munich, after his suicide, all royalties from his estate went to the state of Bavaria, which owns the copyright of Mein Kampf in Germany and has refused to allow publication

The copyright expires at the end of 2015, and Bavaria says it will allow an annotated version of the text to be published

Publication and ownership of the book is restricted or banned in some countries including Argentina, China, the Netherlands and Russia

In other countries, such as India and Turkey, it remains popular - it's estimated that more than 15,000 copies are sold in the US every year

There's another intriguing twist to the story of the English translation. While my grandfather was working on it he employed the help of a German woman (recommended by a half-Jewish writer, who was also the Murphys' landlord). James referred to Greta Lorcke, as she was then, as one of the most intelligent people he'd ever met. But he had battles with her. While he wanted to produce an intelligible translation, in good English, Greta would on occasion alter the translations, to reflect some of Hitler's convoluted and vulgar language. "This annoyed him intensely," my father says. "He would alter it back again."

But there was something else about Greta that my grandfather didn't know at the time.

The serialised edition of Murphy's translation

During the War the Nazis discovered that Greta and her husband, Adam Kuckhoff, were members of a famous Soviet spy ring, known as the Red Orchestra (Rote Kapelle). Adam was executed. Greta had her sentence commuted to life imprisonment. She survived the war, and in her autobiography she describes her first meeting with James Murphy, who she refers to as Mr M.

"I was very impressed by Mr M as he came to meet me in the main lobby. He was a handsome man - 2m tall and carried his 100kg with regal dignity - a man who inspired confidence. The way he discussed his translation work, with which I was to assist him, made me believe he was no friend of National Socialism."

Greta had considerable doubts about translating Mein Kampf, as she explained to my father, years later.

"'Why should I help this man translate this awful book into English?' she wondered. But she consulted her Soviet contacts who explained that it was necessary to translate it into good English," my father says.

"They had heard from the Soviet Ambassador to London, Maisky, who knew Lloyd George quite well. Lloyd George had said to Maisky, 'I don't know why you tell me all these things are in Mein Kampf - I've read it and they aren't.' It turned out that what Lloyd George had read was [the] abridged version, which was only about a third of the length, and which had been controlled to a certain extent by the Nazis. Some of the worst things were taken out of it. So the Russians had said to Greta, 'You must help this man - get this into English!'"

Unfortunately I never met my grandfather. He died of a heart condition in 1946, just before his 66th birthday. This large Irishman from County Cork was a complicated and fascinating man. He was a true polymath, with a deep knowledge of literature, art and science; a journalist, a lecturer, a translator; an expert on Italian fascism and Nazi Germany.

He spoke French, Italian and German fluently. He harboured dreams of a United States of Europe - at peace. Ultimately, though, even if it wasn't his intention, he'll be best known as the man who translated Hitler's Mein Kampf.

Mein Kampf: Publish or Burn? produced by John Murphy with reporter Chris Bowlby was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 11:00 GMT, 14 January - you can now listen to it on the BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.