Crossrail: Who wants to work in a tunnel?

- Published

The £16bn Crossrail project has dug out many miles of tunnels beneath London's streets. The company has taken on thousands of unemployed people and even created a special academy to train them - but who wants a job that takes you underground?

"I would do tunnels before I'd do the Shard, because millions of lives are going to be positively affected by what we are doing right now, for the next 120 years."

Linda Miller, 53, originally from Arizona, is project manager at London's Farringdon site for Crossrail.

She once took to the skies as a helicopter pilot for the US military, but these days is adamant that the most interesting jobs in construction are to be found below ground, working on tunnels.

"Transportation infrastructure in particular feels really, really fantastic," she says. "Our work is more hidden, and that gives the people who work on it an even greater sense of meaning and purpose in what they're doing. When you're working hard underground to make new space that doesn't exist, there's a huge pride in that."

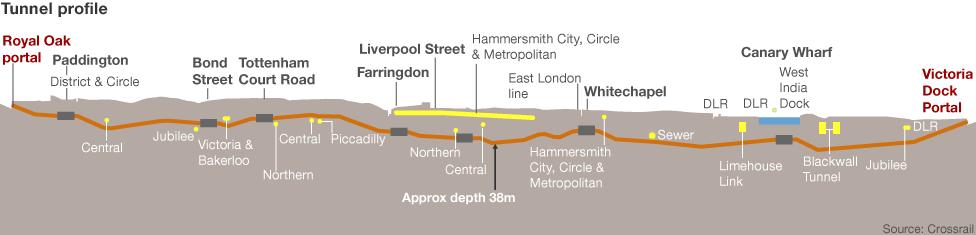

Some 12,000 men and women are working on Crossrail over 45 sites, which will pass through 37 train stations and run 73 miles (118km) from Reading and Heathrow in the west, to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east.

It is due to be completed by 2018.

Leanne Doig says she will tell her own family in future how she worked on the Crossrail project

One of the women working on the Farringdon site is Leanne Doig, who realised as a teenager that she wanted a manual job after her dad failed to put up shelves in her bedroom.

"I was waiting about six, seven weeks," says the 22-year-old from Canning Town. "Ended up doing them myself. I thought, this is more like it. I liked the hands-on experience."

Little did she know that this fledgling success with her hands would eventually lead her to working in the bowels of the capital on the biggest infrastructure project in Europe, up to 40m deep in places.

Doig is a general operative, so can be asked to turn her hand to anything from digging holes to "working with the chippies" - the carpenters. Currently she is helping to build Farringdon station's ticket hall.

"It's exciting for me. But sometimes it can be scary at the same time, because of all the procedures you'd have to go through if you were injured that far underground."

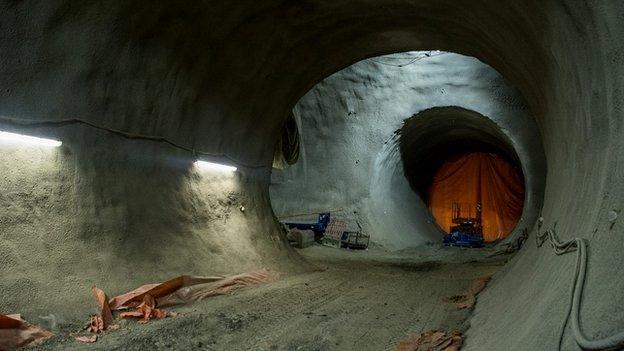

Crossrail's trains will hurtle down this tunnel in the future

This metal frame will be covered in plastic, part of a system to help maintain the ventilation underground

Valerie Todd, talent resources director for Crossrail, says when the company was handed its contract for this enormous project, it was determined to hire local people - broadly defined as those within the radius of the M25 - regardless of whether they'd ever worked in tunnel infrastructure before.

As part of this plan, it created the Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy, external (TUCA), a purpose-built training facility which opened in late 2011 and teaches the sorts of skills required to work in tunnel excavation and underground construction.

About 7,000 people have passed through the academy, 3,000 of whom were the locals Crossrail was keen on recruiting - but some other apprentices were hired directly by contractors.

Having an academy was necessary, Todd says, as the UK had "lost its tunnelling skill base, because that comes from a mining discipline". The shrinking of the mining sector had taken a more general toll.

Crossrail was looking to recruit people who were "unemployed, preferably quite a way from the job market, and for us to do everything that we could to bring them into the workplace" by giving them technical training and safety skills.

These tunnels will be used by passengers to move between platforms

Farringdon Crossrail station, as seen from above

But why would anyone want to work in a tunnel, away from daylight, in a career far removed from anything they'd done before?

"The camaraderie you get when you work down a tunnel, the team work you get - it's amazing," Todd says.

"Everybody looks after each other. It's almost like a family, like a little community. People don't feel like they're going into some nameless, faceless job, where they're just a number.

"For example, people working on tunnel boring machines are on shift for 12 hours and for that time, the crew are your family."

These machines are 150m long and dig the tunnels out, operating 24 hours a day and moving through the earth at a rate of about 100m per week.

Each one is staffed by a 20-strong "tunnel gang" and comes with its own kitchen and toilet.

Todd says tunnelling is an international career, taking people with that particular expertise on projects around the globe. This type of demand, and the skilled nature of the work, contributes to the "very good" pay on offer to tunnel workers.

Project manager Linda Miller says the hidden work of tunnellers gives their work greater significance

Firoz Patel (left), Leanne Doig and Sean Taylor are just starting their careers in construction and tunnelling

Safety is of paramount importance for those working deep underground

British tunnellers will not have to go abroad to stay employed, however.

Projects such as the HS2 high-speed rail line, the Bakerloo and Northern Line upgrades on the London Underground and Thames Tideway, a major new sewer tunnel, mean that there's plenty of work on the horizon for those willing to work beneath street level.

Firoz Patel, 23, from East Ham, has been working as an apprentice steel fixer at Crossrail for the past nine months, for 50 hours a week, meaning he fits the steel bars and mesh which reinforces concrete structures.

Before that, he worked in retail, as a security guard and did admin in an office. "I'm a practical person so I thought it was time for a career change," he says. "When I was offered a job as a steel fixer I had to look up what it was. But then I came down here and saw the reality of it - it's pretty intense.

"Crossrail is a big project and I'm proud to be on it. My work is hidden but I know I've done it. This is something that I see myself doing for a very long time."

Wearing orange safety clothing is compulsory while working in the tunnels

Sean Taylor, 21, from Brixton, has also been an apprentice steel fixer, for eight months. Before that, he was studying electrical installation at college.

Both he and Patel work on the section of the Farringdon tunnel which will become the station platform.

"This job makes you learn things, and you see things you've never seen before, certain machines for the tunnelling. Sometimes it amazes you. It's not a normal job.

"People are quite impressed when I tell them what I do and always want to know what it's like down there. For the first two weeks when I started this job I had aches and strains. Then obviously you toughen up, you get stronger and it's easier from then on."

As for Doig, she takes a personal pride in what they are doing. "It gives me goose bumps to think of what I'm a part of here.

"I can say in 30 years, 40 years' time to my grandchildren - I worked on that Crossrail job."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.