Viewpoint: The roots of the battle for free speech

- Published

Voltaire: Often quoted advocate of freedom of expression

Historian Tom Holland was one of those who tweeted Charlie Hebdo's cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad in the wake of the deadly attack on the magazine's office. Here he explains the ramifications of defending free speech.

Religions are not alone in having their martyrs. On 1 July, 1766, in Abbeville in northern France, a young nobleman named Lefebvre de la Barre was found guilty of blasphemy. The charges against him were numerous - that he had defecated on a crucifix, spat on religious images, and refused to remove his hat as a Church procession went past.

These crimes, together with the vandalising of a wooden cross on the main bridge of Abbeville, were sufficient to see him sentenced to death. Once La Barre's tongue had been cut out and his head chopped off, his mortal remains were burned by the public executioner, and dumped into the river Somme. Mingled among the ashes were those of a book that had been found in La Barre's study, and consigned to the flames alongside his corpse - the Philosophical Dictionary of the notorious philosopher, Voltaire.

Voltaire himself, informed of his reader's fate, was appalled. "Superstition," he declared from his refuge in Switzerland, "sets the whole world in flames."

Two-and-a-half centuries on, and it is the notion that someone might be put to death for criticising a religious dogma that is likely to strike a majority of people in the West as the blasphemy. The values of free speech and toleration for which Voltaire campaigned all his life have become enshrined as the very embodiment of what Europeans, as a rule, most prize about their own civilisation.

Voltaire, with his mocking smile, still serves as their patron saint. In France, where secular ideals are particularly treasured, he is regularly invoked by those who feel the legacy of the Enlightenment to be under threat.

When Philippe Val, the editor of Charlie Hebdo, published a book in 2008 defending the right of cartoonists to mock religious taboos, the title was telling. Reviens, Voltaire, Ils Sont Devenus Fous, he called it - Come Back, Voltaire, They Have Gone Insane. It was not Christians, though, whom Val was principally calling mad.

Between the 18th Century and the 21st, the religious complexion of France had radically altered. Not only had the power of the Catholic Church gone into precipitous retreat, but some six million immigrants belonging to a very different faith had arrived in the country.

Islam, unlike Catholicism, had inherited from the Jews a profound disapproval of figurative art. It also commemorated Muhammad - the prophet believed by his followers to have received God's ultimate revelation, the Koran - as the very model of human behaviour. Insults to him were traditionally held by Muslim jurists to be equivalent to disbelief - and disbelief was a crime that merited Hell.

Not that there was anything within the Koran itself that necessarily mandated it as a capital offence. "The truth is from your Lord, so whoever wills, let him believe; and whoever wills, let him disbelieve." Nevertheless, a story preserved in the oldest surviving biography of Muhammad implied a rather more punitive take. So punitive, indeed, that some Muslim scholars - who are generally most reluctant to countenance the possibility that the earliest biography of their prophet might be unreliable - have gone so far as to question its veracity.

Pens are laid in a pile in tribute to the victims of the Paris attack

The story relates the fate of Asma bint Marwan, a poet from the Prophet's home town of Mecca. After she had mocked Muhammad in her verses, he cried out, "Who will rid me of Marwan's daughter?" - and sure enough, that very night, she was killed by one of his followers in her own bed. The assassin, reporting back on what he had done, was thanked personally by the Prophet. "You have helped both God and His messenger!"

"Ecrasez l'infâme," Voltaire famously urged his admirers: "Crush what is infamous". Islam, too, makes the same demand. The point of difference, of course, is over how "l'infâme" is to be defined. To the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo, who in 2011 published an edition with a swivel-eyed Muhammad on the cover, just as earlier they had portrayed Jesus as a contestant on I'm a Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here, and Pope Benedict holding aloft a condom at Mass, it is the pretensions of authority wherever they may be found - in politics quite as much as in religion.

To the gunmen who yesterday launched their murderous attack on the Charlie Hebdo office, it is the mockery of a prophet whom they feel should exist beyond even a hint of criticism. Between these two positions, when they are prosecuted with equal passion and conviction on both sides, there cannot possibly be any accommodation.

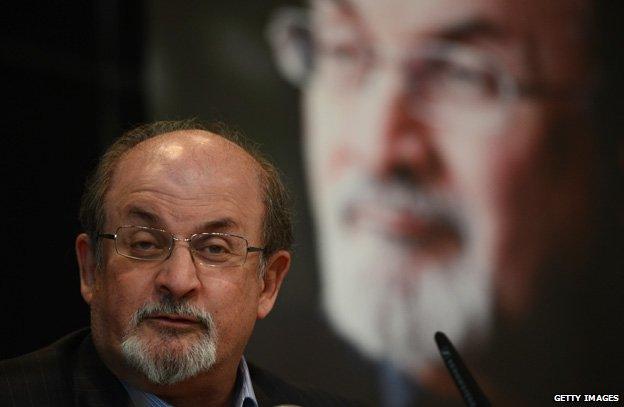

It was the Salman Rushdie affair that served as the first symptom of this. Since then, like a dull toothache given to periodic flare-ups, the problem has never gone away. I myself had first-hand experience of just how intractable it can be in 2012, with a film I made for Channel 4. Islam: The Untold Story explored the gathering consensus among historians that much of what Muslims have traditionally believed about the life of Muhammad is unlikely to be strict historical fact - and it provoked a firestorm of death threats.

Unlike Charlie Hebdo, I had not set out to give offence. I am no satirist, and I do not usually enjoy hurting people's feelings. Nevertheless, I too feel that some rights are worthy of being defended - and among them is the freedom of historians to question the origin myths of religions. That was why, when I heard the news from Paris yesterday, I chose to do something I would never otherwise have done, and tweet a Charlie Hebdo cartoon of Muhammad.

The BBC, by contrast, has decided not to reproduce the cartoon for this article. Many other media organisations - though not all - have done the same. I refuse to be bound by a de facto blasphemy taboo.

While under normal circumstances I am perfectly happy not to mock beliefs that other people hold dear, these are far from normal circumstances. As I tweeted yesterday, the right to draw Muhammad without being shot is quite as precious to many of us in the West as Islam presumably is to the Charlie Hebdo killers.

We too have our values - and if we are not willing to stand up for them, then they risk being lost to us. When it comes to defining l'infâme, I for one have no doubt whose side I am on.

Tom Holland is a writer, broadcaster and historian. His latest book, In The Shadow of the Sword, is an account of the history of Islam. He wrote and presented the documentary Islam: The Untold Story.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox