The Jew who got a job offer from the Nazis

- Published

Before World War Two 170,000 Jews lived in Vienna - by the end there were just 6,000. One of those who fled the Nazis was Freddie Knoller - now 93, he survived a Gestapo interrogation, Auschwitz and a death march in sub-zero temperatures.

"I saw two civilians coming towards me. Each one had a hat on and a long black leather coat, and I recognised them immediately, this must be two people from the Gestapo," says Freddie Knoller.

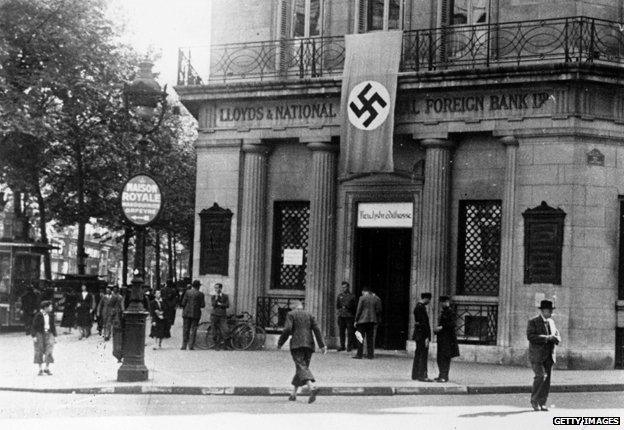

It was July 1943. Twenty-two-year-old Knoller, had managed to obtain false papers and get work in occupied Paris introducing Nazi soldiers to the nightclubs and brothels of the red light district. But that day he was arrested and taken to Gestapo headquarters.

In a large room with a portrait of Adolf Hitler hanging on the wall, one of the officers interrogated him.

"While he was talking, I saw on his desk a plaster head of a human being and he saw me looking at it and he said, 'Oh this plaster head, that's the head of a Jew, because we were taught how to recognise Jews by the structure of their head,'" says Knoller.

"With that he got up from his desk, went behind me and he took my head between his two hands, tracing it. I'm not ashamed to say I wet my pants because I was so sure I would now be recognised as a Jew.

"He said, 'Oh yes, I can see you come from a good German background and I think you should be joining our organisation as an interpreter, you will be earning a lot of money and finally you will be working with your own people.'

"I felt so amazed, laughing [to] myself… 'Wow what an adventure to be able to get away from the Gestapo, and they want me to work with them.'"

But it was a job offer that Knoller had no intention of accepting. He quickly made himself scarce.

This was the third time he had found himself under Nazi occupation. The first, he had to leave his home in Vienna as a 17-year-old in 1938 when Austria was annexed by Germany in the Anschluss.

His parents sent him to stay with friends in Belgium where they thought he would be safe, but when Hitler invaded the country in 1940, Knoller had to flee for a second time.

He chose to go to France. "I read in these naughty books all about Paris, about Montmartre, about the Moulin Rouge with the half-naked dancers on the stage and this is where I wanted to go," he says.

But things went wrong almost immediately. He was arrested at the French border for having a German passport and was interned in a camp for France's enemies in May 1940. After the Nazis invaded France a month later, he managed to escape and finally made his way to the bright lights of Paris.

But his run-in with the Gestapo made him realise it was too dangerous for him to stay there.

Instead of taking up their job offer, he turned to a friend for help and was introduced to the leader of the French Resistance. He went to live in the mountains near the town of Figeac in southern France, fighting the occupying German soldiers.

"It was a great joy for me to fight my enemies instead of earning money from them," says Knoller.

He learned how to shoot a gun and wire up explosives to derail an enemy troop train.

"Our leader… made sure that whenever we put explosives on to the railway line, we hid it with leaves, grass, so it shouldn't be noticed immediately. Then he told us that we should go and observe, but quite far away, what is going to happen, up in the hills.

"The train came, we heard the explosion, we saw the first engine topple over on the side and the whole thing just collapsed, but we ran away immediately back to our resistance group. I must say it was wonderful."

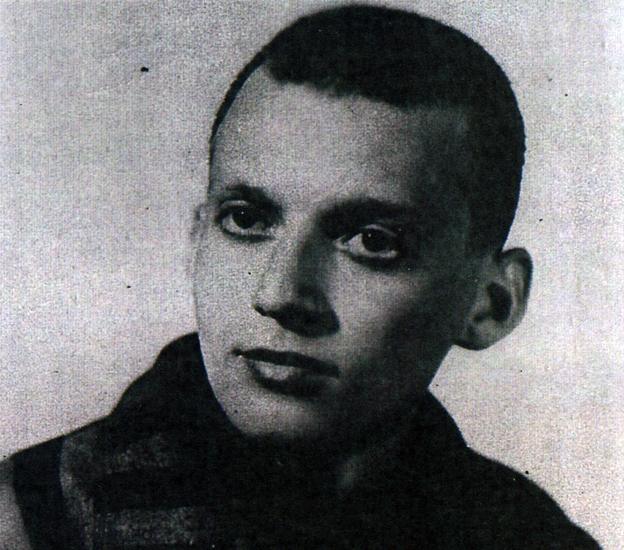

Knoller (far left) with his brothers and parents - he did not learn the fate of his mother and father until 1995

He soon fell in love with a beautiful local girl called Jacqueline. But after an argument, she betrayed him to the Gendarmes.

They burned his body with cigarettes to find out more about his resistance group and when he could not stand the pain any more, Knoller revealed his true identity and was handed over to the Gestapo.

It was September 1943 and the Nazis had finally caught up with him. Knoller was sent to Auschwitz where he was imprisoned until the war was nearly over. He worked in temperatures as low as -25C carrying four stone (25kg) cement bags in the camp and was forced to run with them - he was whipped if he was too slow.

"From time to time we were told to line up in front of the SS and told to walk," says Knoller.

"The SS either said to us go left or go right. I put my chest out and I smiled at them, more or less to say, 'I'm OK to continue working.' I wasn't meek at all about it because I knew if you were ever taken on the left hand side they would gas us."

Knoller talks about his registration at Auschwitz and how he was tattooed on his forearm with the number 157108

In January 1945, as Russian troops approached, Auschwitz was evacuated. Knoller and most of the other prisoners were sent on a 31-mile (50km) death march in the freezing cold to the town of Gleiwitz.

"We walked on that big road on ice and snow and some people just collapsed of the freezing cold in our thin clothes," says Knoller.

"As soon as people could not walk any more the Germans, who surrounded us, shot them. Some people ran away into the woods, the Germans killed them."

Almost 60,000 prisoners from Auschwitz were forced on death marches and more than 15,000 people died.

"I walked and walked without caring what happened to anybody else. We saw people being killed, but it didn't affect me. I'm still walking and I'm still alive, that's the only thought that I had," says Knoller.

As the German army retreated, camps near the eastern front were evacuated and prisoners sent westwards

Those who survived were loaded on to trains and sent to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northern Germany, where Knoller remained until liberation by British troops on 15 April 1945. By the end of the war he weighed just over six stone (41kg).

Afterwards, Knoller travelled to the US and was reunited with his two brothers. He met his British wife Freda there and the couple moved to London.

For 30 years Knoller was unable to speak about his experience of the Holocaust, but he was finally persuaded to do so by his children.

It was not until 1995 that Knoller learned the fate of his parents. They had been deported from Vienna in 1942, and by a strange coincidence were in Auschwitz at the same time as he was, but they were killed in 1944.

"I'm proud to have fought for my life, and proud to be able to tell the world what has happened," says Knoller.

Surviving The Holocaust: Freddie Knoller's War will be broadcast on Thursday 22 January at 21:30 GMT. Or catch up later on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.