Have pictures of Muhammad always been forbidden?

- Published

The French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo has published an issue which commemorates the victims of last week's shootings in France - using an image of the Prophet Muhammad on the cover. Most Muslims say that pictorial depictions of the founder of Islam are forbidden - but has that always been the case in all of the Muslim world?

(This article contains a historical image of the Prophet Muhammad)

If you set aside for a moment the issue of whether satirical cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad are insulting, there's a separate and complicated debate about whether any depiction - even a respectful one - is forbidden within Islam.

For most Muslims it's an absolute prohibition - Muhammad, or any of the other prophets of Islam, should not be pictured in any way. Pictures - as well as statues - are thought to encourage the worship of idols.

This is uncontroversial in many parts of the Islamic world. Historically, the dominant forms in Islamic art have been geometric, swirling patterns or calligraphic - rather than figurative art.

Muslims point to a verse in the Koran which features Abraham, whom they regard as a prophet:

"[Abraham] said to his father and his people: 'What are these images to whose worship you cleave?' They said: 'We found our fathers worshipping them.' He said: 'Certainly you have been, you and your fathers, in manifest error.'"

Yet there's no ruling in the Koran explicitly forbidding the depiction of the Prophet, according to Prof Mona Siddiqui from Edinburgh University. Instead, the idea arose from the Hadiths - stories about the life and sayings of Muhammad gathered in the years after his death.

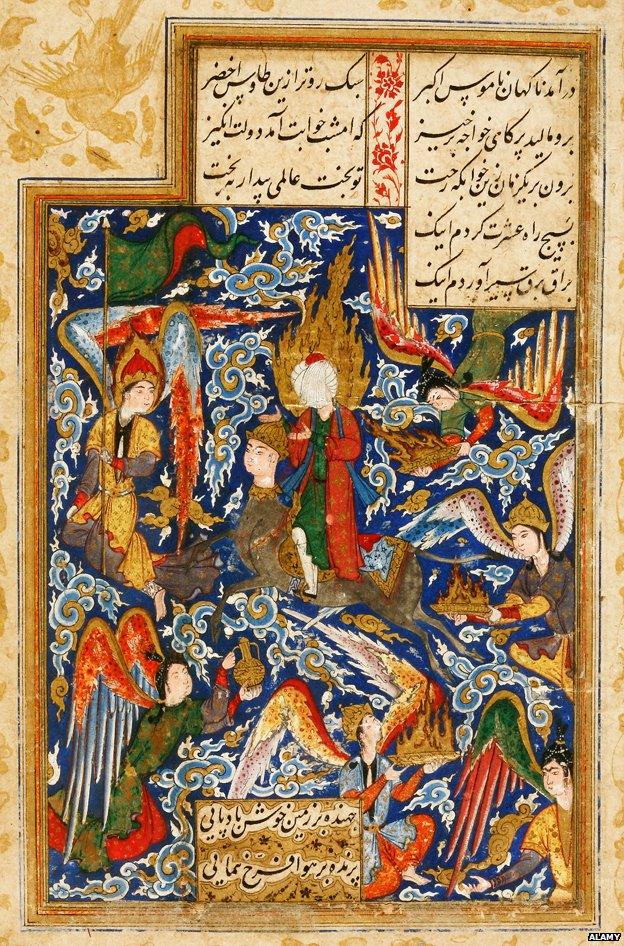

Siddiqui points to depictions of Muhammad - drawn by Muslim artists - dating from the Mongol and Ottoman empires. In some of them, Muhammad's facial features are hidden - but it's clear it is him. She says the images were inspired by devotion: "The majority of people drew these pictures out of love and veneration, not intending idolatry."

At what point then, did depictions of Muhammad become haram, or forbidden?

Many of the images of Muhammad which date from the 1300s were intended only to be viewed privately, to avoid idolatry, says Christiane Gruber, associate professor of Islamic Art at Michigan University. "In some ways they were luxury items, perhaps in libraries for the elite."

Such items included miniatures which showed characters from Islam.

Gruber says the advent of mass-circulation print media in the 18th Century posed a challenge. The colonisation of some Muslim lands by European forces and ideas was also significant, she says.

The Islamic response was to emphasise how different their religion was to Christianity, with its history of public iconography, Gruber argues. Pictures of Muhammad started to disappear, and a new rhetoric against depictions emerged.

But Imam Qari Asim, of Leeds Makkah Mosque, one of the largest in the UK, denies there has been a significant change. He maintains that the effect of the Hadiths, with their injunctions against any images of living things, is automatically a prohibition on depictions of Muhammad.

He says the medieval images have to be understood in context. "The majority of these images relate to this particular Night Journey and the ascension to Heaven. There is a ram or a horse. He is on the horse or something like that.

"The classical scholars have very strongly condemned those depictions as well. But they do exist."

A key point is that they are not simple portraits of Muhammad. Asim also argues that the subject of many of the images is unclear. There is a question of whether all of these depictions actually intended to portray the Prophet or a close companion involved in the same scene, he suggests.

Prof Hugh Goddard, director of the Alwaleed Centre for the Study of Islam in the Contemporary World in the University of Edinburgh, says that there has been a change.

"There isn't unanimity in either of the foundational sources - the Koran and the Hadiths. The later Muslim community has tended to have different views on this question as on others."

The Arab scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, whose teachings paved the way for Wahhabism, the dominant form of Sunni Islam in Saudi Arabia, was a key figure.

"The debate has become much more vigorous - particularly associated with the movement of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. You had suspicion of veneration of anything other than God. That included the Prophet.

"There has been a significant change over certainly the last 200 years, but probably 300 years."

The situation is different with sculpture or any other kind of three-dimensional representation, notes Goddard, where the prohibition has always been clearer.

Image from a 16th Century Iranian manuscript showing the ascension to Heaven

For some Muslims, says Siddiqui, the aversion to pictures has even extended to a refusal to have pictures of any live being - human or animal - in their homes.

The prohibition against depiction didn't stretch everywhere though - many Shia Muslims appear to have a slightly different view. Contemporary pictures of Muhammad are still available in some parts of the Muslim world, according to Hassan Yousefi Eshkavari, a former Iranian cleric, now based in Germany. He told the BBC that today, images of Muhammad hang in many Iranian homes: "From a religious point of view there is no prohibition on these pictures. These images exist in shops as well as houses. They aren't seen as insulting, either from a religious or cultural viewpoint."

Differences in approach among Muslims can be seen along traditional Shia/Sunni lines, but Gruber says that those who claim a historical ban has always existed are wrong.

It's an argument that many Muslims would not accept.

"The Koran itself doesn't say anything," Dr Azzam Tamimi, former head of the Institute of Islamic Political Thought told the BBC, "but it is accepted by all Islamic authorities that the Prophet Muhammad and all the other prophets cannot be drawn and cannot be produced in pictures because they are, according to Islamic faith, infallible individuals, role models and therefore should not be presented in any manner that might cause disrespect for them."

He is not convinced by the argument that if there are medieval depictions of Muhammad that suggests there is no absolute prohibition. "Even if it were that would have been condemned by the scholars of Islam."