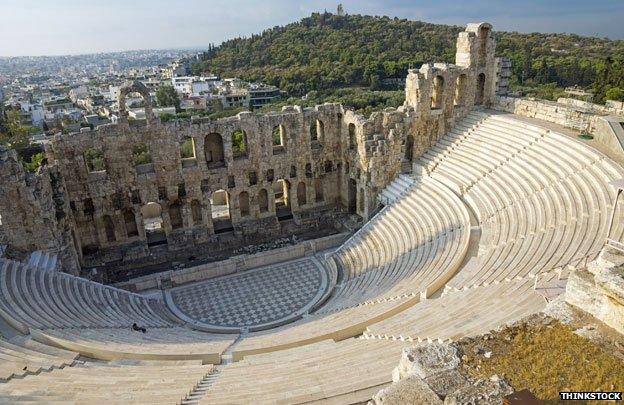

Viewpoint: Would Athenian-style democracy work in the UK today?

- Published

Ancient Athens operated a unique system of direct democracy in which all citizens could vote on laws themselves rather than electing representatives to do it for them. Could such a system operate in the modern UK, asks historian Paul Cartledge.

We're all democrats now. "We" in the liberal, late-capitalist West, that is, whether we are upper-case democrats (Christian Democrats, US Democratic Party supporters, etc) or lower-case. And we have been that since roughly the mid-19th Century.

During the course of the long and horrendous 20th Century, we recovered some of the original ancient Greek term's ideological resonance. Demokratia - "people-power" - was born in classical Athens around 500 BC, explicitly as an anti-tyrannical political mode of self-governance.

Against any simple, straightforward application of ancient Greek democratic ideas and practices to our modern democracy, however, there stands the apparently insuperable obstacle of incommensurable differences of scale.

Even Athens, by far the largest polis - a city or citizen-state - in ancient Greece in terms of the size of its adult male citizen body (60,000 maximum), was minuscule by our standards, though for Aristotle (not an ideological democrat) even that was way too large.

Yet thanks to new digital technology and instant online intercommunication, it is theoretically possible for us today to replicate virtually (if not necessarily virtuously) the conditions of an ancient Athenian primary decision-making assembly by mass meeting and face-to-face voting.

Then there is the further obstacle of our very different, indeed contradictory notions of the state, political parties, and representative government, all of which for an ancient Greek democrat would add up to something far more like oligarchy ("rule of the few") than anything he would recognize as democracy.

Unlike our representative democracy, or politics at a distance, however, ancient Greek politics were always face-to-face, and often enough in-yer-face. A frequently fevered contention for domination or control of public affairs, constantly risking civil dissension or even outright civil war.

It was this pressure-cooker, zero-sum character of ancient Greek politics that helps explain why the compound noun demokratia, so far from being a descriptively innocent term, was always loaded - in the artillery sense as well as the gentler metaphorical one.

The -kratia component of demo-kratia was derived from kratos, which meant unambiguously and unambivalently power or strength. Demos, the other component, meant "people" - but which people, precisely?

Power to the people

At one extreme it could be taken to mean all the people - that is, all the politically empowered people, the adult male citizenry as a whole. At the other ideological pole, it referred to only a section of the citizen people, the largest, namely the majority of poor citizens - those who had to work for a living and might be in greater or less penury.

Against these masses were counterposed the elite citizens - the (more or less) wealthy Few. For them, and it may well have been they who coined the word demokratia, the demos in the class sense meant the great unwashed, the stupid, ignorant, uneducated majority.

So, depending where you stood on the social spectrum, demokratia was either Abe Lincoln's government of, by and for the people, or the dictatorship of the proletariat. This complicates, at least, any thought-experiment such as the one I'm about to conduct here.

BBC Democracy Day

Democracy Day takes place on Tuesday 20 January, across BBC radio, TV and online

A look at democracy past and present, encouraging debate on its role and future

2015 marks the 750th anniversary of the first parliament of elected representatives at Westminster

It also sees the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta - a touchstone for democracy worldwide

Go to the BBC News website's Democracy Day page, external, for analysis, backgrounders and explainers on the debate

However, what really stands in the way is a more symbolic than pragmatic objection - education, education, education.

For all that we have a formal and universally compulsory educational system, we are not educated either formally or informally to be citizens in the strong, active and participatory senses. The ancient Athenians lacked any sort of formal educational system whatsoever - though somehow or other most of them learned to read and write and count.

On the other hand, what they did possess in spades was an abundance of communal institutions, both formal and informal, both peaceful and warlike, both sacred and secular, whereby ideas of democratic citizenship could be disseminated, inculcated, internalised, and above all practised universally.

Annual, monthly and daily religious festivals. Annual drama festivals that were also themselves religious. Multiple experiences of direct participation in politics at both the local (village, parish, ward) and the "national" levels. And fighting as and for the Athenians both on land and at sea, against enemies both Greek and non-Greek (especially Persian).

Democratic leader Pericles

Formal Athenian democratic politics, moreover, drew no such modern distinctions between the executive, legislative and judicial branches or functions of government as are enshrined in modern democratic constitutions. One ruled, as a democratic citizen, in all relevant branches equally. A trial for alleged impiety was properly speaking a political trial, as Socrates discovered to his cost.

In short, ancient Athenian democracy was very far from our liberal democracy. I don't think I need to bang on about its conscientious exclusion of the female half of the citizenry, or its basis in a radical form of dehumanised personal slavery.

So why should we even think of wanting to apply any lesson or precedent drawn from it to our democracy today or in the future? One very good reason is the so-called "democratic deficit", the attenuation or etiolation of what it means to be, or function fully as, a democratic citizen.

The recent Scottish referendum, whatever one may think about its outcome, was quite extraordinary if for nothing else for its very process - a one-off, once-for-all popular democratic vote, the majority on the day (plus of course the postal voters) winning and taking all (but the Athenians would have raised an eyebrow at the voting equality of 16 and 17-year olds - 18 was their age of political majority).

There's another dimension, too, that I would myself wish to recover from the ancient Athenian democratic experience - the Athenians were incredibly hot on responsibility or accountability.

Most of their office-holders were, as a matter of fact, selected by the lottery rather than by election, the latter being considered in principle un-democratic, since it favoured members of the few rather than the masses.

But even allotted officials were no less subjected to official public scrutiny and audit than were the elected high officials who served the community as generals or treasurers or water-commissioners.

All too easily today, in our era of cabinet government and prime-ministerial autocracy, it is possible for our high officials to evade even routine accountability for their actions or decisions. Abolition of parties is another plank in my own personal neo-democratic platform - but putting the case for that must await another occasion.

Tyrant

Another word of original ancient Greek provenance, meaning an autocrat who rules, often by force but always outside and usually above the existing laws

There were plenty of those around in classical Greece, outside democratic Athens, but the word came to acquire also a specifically "barbarian", non-Greek connotation

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.