Simon de Montfort: The turning point for democracy that gets overlooked

- Published

In June the world will celebrate 800 years since the issuing of Magna Carta. But 2015 is also the anniversary of another important, and far more radical, milestone in British democratic history, writes Luke Foddy.

Almost exactly 750 years ago, an extraordinary parliament opened in Westminster.

For the very first time, elected representatives from every county and major town in England were invited to parliament on behalf of their local communities.

It was, in the words of one historian, "the House of Commons in embryo".

The January Parliament, which first met on 20 January 1265, is one of the most significant events in British democratic history. The election of two knights from every shire and two burgesses from the towns helped establish the two-member county constituencies that endured until the 20th Century.

The delegates coming to parliament in 1265 even had their costs covered - a sort of 13th-Century MPs' expenses.

But for all its importance, the January Parliament remains little-known beyond academic circles, although the BBC will be marking the anniversary with a day of coverage focusing on democracy.

In part, this may be down to the eclipsing effect of Magna Carta on this remarkable step towards representative government.

But the 1265 Parliament went much further than Magna Carta in shaping our political process.

"The Great Charter laid down the first written constitution, but it was primarily a charter for the elite," explains Professor David Carpenter, author of a new book on Magna Carta. "It did not envisage anything resembling a House of Commons.

"It is not until 1265 that the momentous step is taken to invite the commons to parliament."

Parliaments had, of course, existed long before 1265, but they were traditionally elite gatherings between the king and his chosen advisors. Knights, too, had been summoned to parliament before, in 1254, but only to discuss taxation.

At the January Parliament of 1265, however, both the counties and boroughs were to be represented, and the parliament was concerned with the wider business of the realm, not just taxation.

This was, therefore, a landmark moment in England's political evolution.

The story behind this radical reform is a medieval classic of revolution and rebellion - a drama fuelled by idealism, pragmatism and ambition whose legacy is still felt today.

And like many extraordinary moments in history, it was the product of extraordinary times.

The ruling king in 1265 was Henry III, but Henry wasn't really ruling anything. It was Simon de Montfort, the rebel earl of Leicester, who was in control, having seized power the year before.

Montfort, who called the January Parliament, was the leader of a political faction that sought major reform of the realm. Fed up with Henry's misrule, as they saw it, these barons had confronted the King and, at a parliament in Oxford in 1258, forced him to adhere to a radical programme of reform. This resulted in an appointed council sharing power with the monarch.

These reforms were enshrined in the Provisions of Oxford, which for the first time defined the role of parliament in government.

Later reissued as the Provisions of Westminster, they specified that parliaments should be held three times a year to "discuss the common business of the realm" - a major shift from their usual purpose of granting taxes as set out by Magna Carta.

By 1261, however, Henry's position had grown stronger, and he rid himself of the reformers' shackles. "I'd rather break clods behind the plough," he is supposed to have declared, "than rule by the Provisions!"

It is perhaps testament to the ideological fervour of the time that Henry's betrayal of the barons' reforms provoked civil war, but war is indeed what followed.

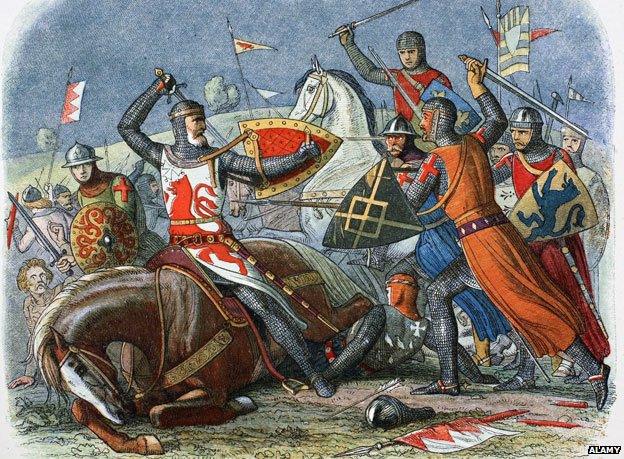

In May 1264 Montfort won a stunning victory at the battle of Lewes, where both King Henry and his heir, the future Edward I, were taken prisoner. He was now the de facto ruler of England, governing in King Henry's name.

This was revolutionary stuff. Four centuries before Oliver Cromwell would overthrow Charles I, another English King had been reduced to a figurehead.

Magna Carta

Magna Carta originated in 1215 as a peace treaty between King John and a group of rebellious barons

The original document was written in Latin on parchment made from animal skin

The name didn't emerge until the document's re-issue in 1217. It became known as 'The Great Charter' to differentiate it from the smaller 'Charter of the Forest' issued at the same time

Yet securing the kingdom proved harder than winning it for Montfort, particularly as the majority of the magnates did not support him.

Montfort lacked authority as the country's effective ruler as well as support from the baronage, so needed the backing of as wide a section of society as possible, says John Maddicott, former fellow in medieval history at Exeter College, Oxford, and author of The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327.

"The knights and burgesses helped to counterbalance this weakness. They were probably seen as useful emissaries, returning from the parliament to their localities to spread the news of the reforms being undertaken. They could be used to build support for Montfort beyond their own ranks and throughout the country."

Yet he wasn't just motivated by the need to secure power.

"Montfort was an ideologically driven man," says Carpenter. He was strongly influenced by churchmen who taught that great men should be concerned with the poor and that a ruler should benefit wider society. In his will of 1259, he admitted to having concerns that he may have oppressed peasants on his lands.

Despite this piety, Montfort was forever stalked by a fierce avarice, which manifested itself during the 1265 Parliament.

The assembly opened with the reaffirming of a constitution that Montfort had established after the battle of Lewes, but this was couched with threats against anyone who defied it. As the parliament progressed, it became clear that the earl was positioning himself for greater power. A London chronicler observed simply: "Simon de Montfort appropriated for himself the earldom of Chester."

The effect of all this was the loss of Montfort's key ally, the earl of Gloucester, who defected to the Royalists. This was a disaster, and marked the beginning of the end for the earl of Leicester.

The battle of Lewes

The Battle of Lewes took place on May 14 1264 between the armies of King Henry III and de Montfort

De Montfort's forces were outnumbered by about two to one

The king had stopped at Lewes, in Sussex, to await reinforcements and rest his army, allowing de Montfort's men to march quietly uphill to get the best view of the town ready for attack at dawn

Fighting spilled into the town and flaming arrows were fired into the thatched roofs of the houses to stop de Montfort's troops taking up positions there

Growing opposition to Montfort's regime led to a fresh outbreak of war, and he was slain at the battle of Evesham in August 1265 - an encounter so vicious it shocked contemporaries. "The murder of Evesham," wrote Robert of Gloucester, "for battle it was none."

Regardless of his motivations, Montfort's parliament has earned him a global reputation as a proponent of democracy, particularly in countries with a revolutionary past.

In Washington DC, a relief of the earl adorns the wall of the House of Representatives; his reforms chimed well with the American Revolution's call for "no taxation without representation". Napoleon even described him as "one of the greatest Englishmen".

Montfort has even earned the nickname "Father of the House of Commons", with a Victorian scholar stating that "the idea of representative government ripened under his hand".

But is this reputation deserved, and how should the 1265 Parliament be remembered today? "My own view is that Montfort's parliament sets the pattern for the future," says Carpenter.

BBC Democracy Day

Democracy Day takes place on Tuesday 20 January, across BBC radio, TV and online

A look at democracy past and present, encouraging debate on its role and future

2015 marks the 750th anniversary of the first parliament of elected representatives at Westminster

It also sees the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta - a touchstone for democracy worldwide

Go to the BBC News website's Democracy Day page, external, for analysis, backgrounders and explainers on the debate

"We can't say for certain that the House of Commons wouldn't have evolved without Montfort's contribution, but he certainly accelerated its development."

But we should probably resist the Victorian lamentations of him as a hero of democracy, says Maddicott.

"If Montfort was 'the father of the House of Commons' he was so only, as it were, by accident. The summoning of knights and burgesses in 1265 was an expedient, not a piece of farsighted constitutional planning."

Later this year, hundreds of MPs from across the UK will be elected in what promises to be one of the most volatile elections in recent years.

It is perhaps appropriate, then, that they will be following a tradition which began amid a highly charged political climate some 750 years ago.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.