How have passport photos changed in 100 years?

- Published

It's 100 years since British passports first included photographs. How have they changed?

It can be a pain getting passport photos right. Smiling, frowning, hats (unless worn for religious reasons), leaning sideways, dark backgrounds, hair over eyes, red eye, glasses, sunglasses - there is a long list of no-nos, external. Anything wrong and Her Majesty's Passport Office may return the application.

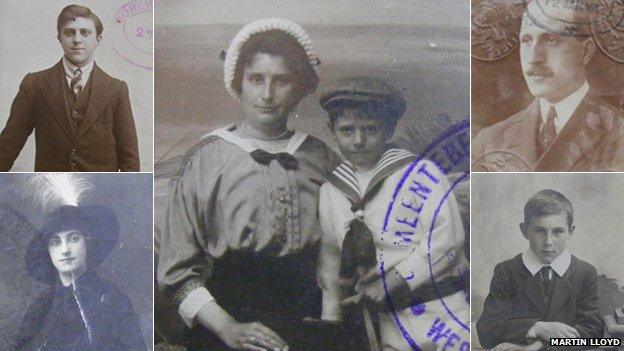

But it hasn't always been like this. When the British government introduced passport photographs in February 1915, the rules were more lax. Whole families, rather than just one person, could be shown. As long as faces were visible, the pose and location of those involved did not matter.

Rather than sit in a booth as one would today, Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in 1915, stood with his wife as his two sons sat in a dog cart.

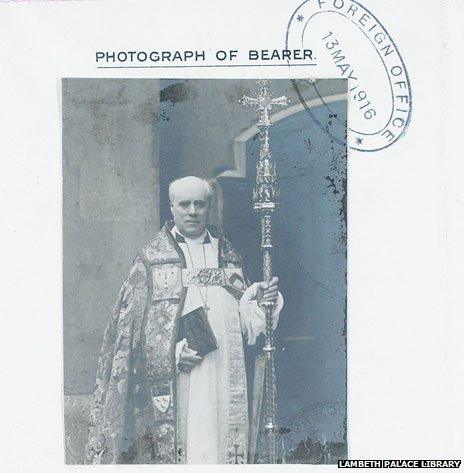

A year later, Archbishop of Canterbury Randall Davidson appeared in his robes, crozier - the staff signalling care of his flock - in hand. The photograph was used for a passport allowing him to visit troops on the Western Front.

Archbishop Davidson's passport for his visit to the front in May 1916

In France, where there was a similar lack of rules, a woman wore a hat looking like a dead pheasant. One mother and child were even photographed on the beach.

"Although photography had been around for more than half a century, its adoption seems to have caught the authorities by surprise," says Martin Lloyd, external, author of The Passport: The History of Man's Most Travelled Document. "They made no rules on how to pose for a picture. They were simply asked to send one in. So they did."

French woman's passport photo with a pheasant-style hat

British passports came in the form of a foldable single sheet of paper. The individualism shown by applicants was perhaps a symptom of a longstanding aversion to officialdom. In 1835, Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston became embroiled in a row with the Belgian government, which had told him British passports should include physical descriptions of holders, such as height and eye colour. He refused, calling such requirements "degrading and offensive".

"He didn't want British people being perused by foreigners," says Lloyd, who worked as an immigration official for 25 years. "That situation continued until the beginning of World War One."

Other countries, including the US and France, started adding descriptions of people's physical characteristics during the 19th Century. By the time WW1 started in 1914, there were widespread fears of German spies operating in Britain, so the lack of a photograph or description on the country's passports came in for greater criticism.

Concerns increased following the capture and execution, in November 1914, of Carl Hans Lody, who had spied on Britain for Germany using a fake US passport, external. "They realised in Britain that the passport as it was did not in fact identify the people," says Lloyd.

The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act of 1914 made both a photograph and a personal description compulsory. Not all were happy with official amendments. Just a fortnight after the law came into force in 1915, the explorer and natural historian Bassett Digby wrote to the Times about the Foreign Office's "high-handed methods".

"On the form provided for the purpose I described my face as 'intelligent'," he complained. "Instead of finding this characterisation entered, I have received a passport on which some official, utterly unknown to me, has taken it upon himself to call my face 'oval'."

Florence Varty, London 1915 and Ethel Homes, 1920 - cut from a group photograph

The passport, the first known English version of which dates back to the early 15th Century, had to be signed by the foreign secretary until 1857 and featured a printed signature afterwards.

A further change came in 1920, following a decision by the League of Nations to standardise passports. The blue cardboard-covered British booklet passport, the last of which expired in 2003, came into being. This was designed to prevent excessive folding of the single-sheet version, known to damage enamelled photographs.

By 1926, when the second version of the booklet passport was introduced, the requirement was for two duplicate, unmounted photographs printed on thin paper, "full face" showing, with no hats worn, which remains the norm. Pictures had to be a certain size to fit the box provided. This meant an end to the early free-for-all.

In 1941, the government specified the photograph size in inches, rather than just "small".

Montage of Michael Pritchard's passport photos

Coin-operated photo booths, with origins as far back as the 1880s, came into wider usage in the 1950s, the same time as mass overseas tourism began, further homogenising passports.

"The very precise requirements of the Passport Office mean that passport photos are more standardised than they have ever been since 1915," says Michael Pritchard, external, director-general of the Royal Photographic Society, external. "No smiling, straight-on and white backgrounds don't provide the flattering images of the traditional High Street photographer and we've probably lost something, which is a shame, especially as we all have to live with that image for 10 years."

Smiling was banned in 2004, external, along with long fringes and dummies in babies' mouths. Today, passports, which come in the standard burgundy covers used within the European Union, must include colour photographs measuring 45mm by 35mm. There are more than 20 separate stipulations. Part of the reason is the introduction of biometrics - using the distances between facial features for more reliable identification - in 2006.

There is slightly more leeway for children, who have had to have passports separate from their parents since 1998. They can still smile, not having to adopt a "neutral" expression. Even so, it's a long way from the freedoms of 100 years ago.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.