Bantams: The army units for those under 5ft 3in

- Published

A century ago the British Army set up Bantam battalions for men under 5ft 3in. Why were short men put in special units during World War One?

Imagine the army had a ban on short men. Then scrapped it on condition that those below a certain height were put together into special "short stature" units.

It sounds far-fetched. But this is exactly what happened in World War One.

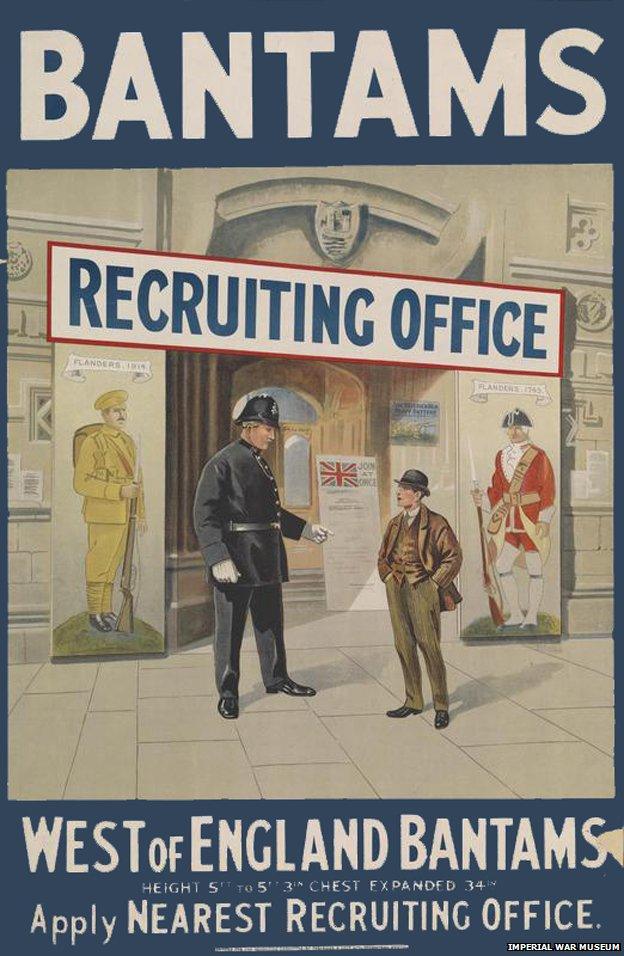

When hostilities began in August 1914, the minimum height for a soldier in the British Army was 5ft 3in (160cm). Thousands of men who wanted to fight were turned away from recruiting offices, seemingly surplus to requirements. There was outrage.

One case struck a nerve. A Durham miner whose name is not known, was stopped from joining up for being 5ft 2in. The story goes - the exact facts are hard to verify - that he walked from recruiting office to recruiting office but in each was told the same thing. By the time he reached Birkenhead on Merseyside he was so infuriated that he threatened to fight any man who said that the missing inch mattered. Hearing of his plight, the local MP Alfred Bigland, wrote to the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener.

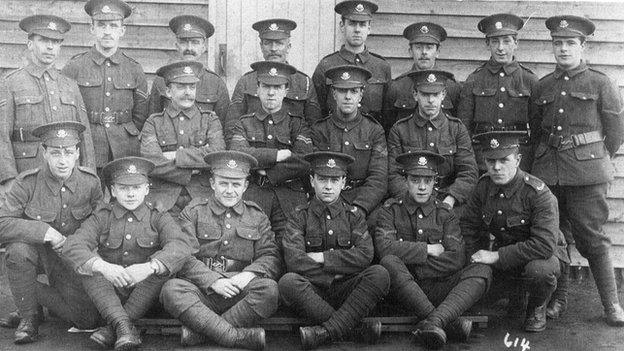

Bigland asked for permission to set up a unit for short, able-bodied men who wished to fight for their country. The War Office gave its blessing. Soon 3,000 men who'd been barred from the army were selected for two Birkenhead battalions. Called Bantam battalions they were reserved for men of 5ft to 5ft 3in with an expanded chest of 34in.

The idea quickly spread to other parts of the country. By the end of the war, 29 Bantam battalions had been created across three divisions - two British and one Canadian. Assuming roughly 1,000 men in each battalion, and allowing for casualties and replacements, more than 30,000 Bantam soldiers enlisted.

It was a dramatic turnaround. In the early phase of the war the army had used height restrictions to control numbers. In September 1914 the height requirement was raised from 5ft 3in (160cm) to 5ft 6in (167cm). The reason? The authorities couldn't cope with the flood of recruits, says Laura Clouting, a historian at the Imperial War Museum. In the first two months of war, three-quarters of a million men volunteered to fight, leading to overcrowding at recruiting offices.

Then the rate of joining slowed. The height minimum was lowered to 5ft 4in in October, and in November to 5ft 3in. The following July, with the Western Front stuck in bloody stalemate, the minimum dropped to 5ft 2in. Average height for men in 1914 would have been about 170cm (5ft 6in).

So why didn't the authorities simply lower the height restriction to 5ft? Retired Major Andrew Greenwood, whose great uncle fought and died for the Bantams, says it was administratively easier for the War Office to tell towns around Britain to "crack on" and raise their own Bantam battalions than to have to incorporate the men themselves. In the early part of the war it wasn't envisaged that these battalions would be needed. Few apart from Kitchener, who predicted the war would be won by the "last million men", realised the conflict would go on so long.

Then there was the idea of men united by a common bond. "It was like the Pals battalions [of friends from the same area]," says Clouting. The word Bantam evoked an aggressive chicken - this was the battalion emblem - or a small-framed boxer. Their image was small, hard, plucky men - often miners or shipbuilders - fighting for their country.

Throughout history, tall soldiers have often been prized. King Frederick I of Prussia brought giants together for his Potsdam Grenadiers. The men had to be about 6ft 2in. They were recruited from all over Europe, if necessary by force. But concentrating short men in one place - as the Bantams did - seems exceptional.

Military historian Antony Beevor says an emphasis on height may sometimes be about practicalities but more often seems to be about projecting power. "In Chile under Pinochet you can see from photographs how officers were half a head to a head taller than their soldiers in march pasts. That might also have been true of the British in World War One."

Indeed officers in Bantam battalions were "normal" size. One of them was the future Field Marshal Montgomery, then Brigade Major of the 104th (Bantam) Brigade.

Other units could be protective of the Bantams in a way that might be seen as patronising today. A private in the Guards Division - renowned for their height - wrote in 1916: "After we finished telling the Bants they had duck's disease we had to take a lot of very funny insults in turn. Very sharp tongues they have, and we've taken to the little chaps right away."

Some, like the Highland Light Infantry's 18th Battalion, gained notoriety.

"Their quarrelsome reputation was legendary," wrote Sidney Allinson in his book The Bantams. After frequent bar brawls they became known around Glasgow as the Devil Dwarfs.

Author William Boyd seems to have used the HLI for the fictional Bantams - the 17th/3 Grampian Highlanders - in his novel the New Confessions. They are presented as hard-as-nails Glaswegians who terrify their taller ex-public school comrades.

Among historians, opinion on the effectiveness of Bantam battalions varies.

"For all their recalcitrance, they had proved to be readily trained into smart soldiers on the barrack square and the assault course," writes Allinson. He quotes a raid on a German trench in June 1916 by the 14th Gloucester that became a hand-to-hand fight. At the end, 30 Germans and eight British lay dead, he writes, and the British had captured a Maxim heavy machine gun.

From William Boyd's The New Confessions (1987)

In William Boyd's 1987 novel The New Confessions, the protagonist, John James Todd describes an encounter during WW1 with the Bantams:

"We came out of the fire-bay. Five very small men - very small men indeed - sat around a tommy-cooker brewing tea. They looked at us with candid hostility. They wore kilts covered with canvas aprons. Their faces were black with mud, grime and a five-day growth of beard. Two of them stood up. The tops of their heads came up to my chest. Neither of them could have been more than five feet tall. Bantams…"

Height differences could lead to problems. An unhappy sergeant major in the Northumberland Fusiliers complained: "Sir, them bloody little dwarfs have built up the fire steps so they could see over. Now when my lads stand up, half their bodies are above the parapet." The Bantams were told to put two sandbags on the step instead.

The Battle of the Somme took its toll on Bantam morale and credibility, historian Peter Simkins wrote in his essay "Each one a pocket Hercules". It was much harder for the Bantams, as opposed to regular army battalions, to find decent replacements. A Brigadier-General Marindin complained about the physical abilities of some later recruits.

In the last week of 1916, 26 Bantams in the 19th Durhams were sentenced to death for cowardice or leaving their posts. Only three were executed, the others had their sentences commuted. "The fact that some of the first Bantams to join up had in late 1916 been found wanting tends to reinforce the conclusion that it was not just the later drafts who were sub-standard," Simkins writes.

The Bantam experiment was over. The 35th division's sign was changed from a Bantam cock to seven interlocked 5s. Its soldiers were re-examined by medical experts and those deemed fit to fight were merged with conventional army units.

But there was redemption of sorts. The 35th Division, now with a mixture of Bantams and regular soldiers, recorded a success rate in battle of 60% in the Hundred Days offensive of 1918 - above the Second Army average.

The experiment was not a failure, says Greenwood. "It did what it could do at the time." There were many moments of heroism and it showed the willingness of smaller men to fight for their country. One of the problems was that the replacement Bantams were either undernourished or underage - it was easier to lie about how old you were in a battalion for short men, he says.

There's also some research suggesting that short men were more likely to be killed in World War One. A paper published by Oxford University Press for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology suggested that taller British soldiers were more likely to survive, external. The mean height difference between those who survived and were killed was nearly one inch (2.37 cm), according to the research.

In this age of anti-discrimination, creating Bantam battalions is unthinkable. Today a British soldier can be just 4ft 10in tall (148cm). Drivers need to be 5ft 2in (158cm).

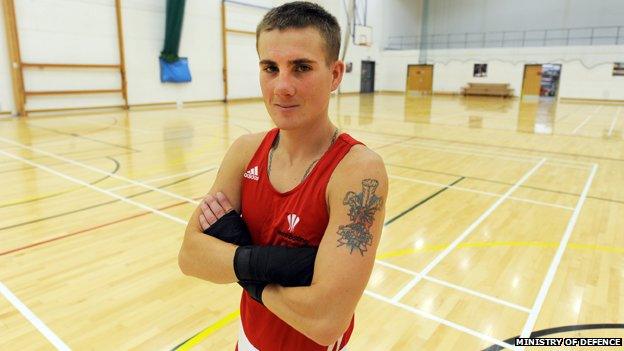

Lance Corporal Ashley Williams of the 1st Battalion the Royal Welsh is 5ft 3in. "I've had no disadvantage of any sort as an infantry soldier," he says. "I carry a lot of weight on my back. Being smaller is not a problem if you've got good upper body and leg strength."

Lance Corporal Ashley Williams is 5ft 3in

Weight was a bigger hurdle for Williams. The Army has a minimum weight rule of 9st 5lbs (60.4kg). As a light flyweight boxer, he was way below this and had to put on a stone and a half. Now a member of the Army boxing team, an exception has been made - he boxes at a weight of 7st 10lbs.

The Bantams experiment is "very surprising", Williams says. Army units work as a team so it makes sense to have a mix of physical capabilities. "Sometimes having a small individual in a team really helps. I can camouflage myself better probably than a big person can." It's part of what makes the Gurkhas good at what they do, he says.

Diversity would not have been in the lexicon of most commanders in 1914. But commanders could also have made better use of shorter units. And late on in the war, this began to happen. After the Bantams were abolished some of them were transferred to tunnelling and tank units where being short was an advantage.

More about World War One

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.