Free childcare in the US: A forgotten dream?

- Published

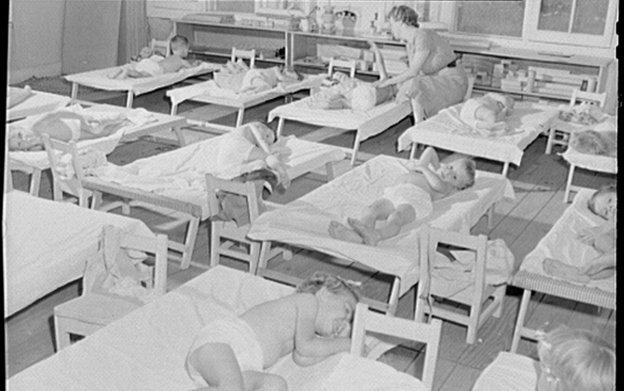

Nap time at a government nursery in 1942

A US wartime childcare programme was recently praised during a landmark presidential address. So what were the Kaiser childcare centres of the 1940s?

It sounds like a progressive dream found only in Scandinavia - employers who offer on-site, affordable, education-based childcare 24-hours a day.

Healthy and affordable pre-cooked meals are sent home with the children so parents don't have to cook.

In fact, such a scenario was an American reality for workers during World War Two. President Obama used his State of the Union address this year to laud the programmes and urge the nation to "stop treating childcare as a side issue, or a women's issue" and to make it a national economic priority.

"During World War Two, when men like my grandfather went off to war, having women like my grandmother in the workforce was a national security priority - so this country provided universal childcare," President Obama said. "In today's economy, when having both parents in the workforce is an economic necessity for many families, we need affordable, high-quality childcare more than ever."

In the budget released this week. Mr Obama didn't deliver universal care - instead, he offered an increased tax credit for childcare costs.

World War Two marked the first and only time in US history that the government funded childcare for any working mother, regardless of her income. The programmes were created as women entered the workforce in droves to help with the war effort.

The Kaiser Company Shipyards in Oregon and California were at the vanguard of progressive childcare during World War Two. They hired skilled teachers and some offered pre-made meals for mums to take home and heat up. Some even offered personal shoppers to help women juggle home life and the building of combat ships.

Children of defence workers at a plant in Childsburg, Alabama eat lunch in their nursery

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was so impressed that she visited several of the Kaiser centres and urged companies across the United States to emulate the model.

"I don't understand why it hasn't come back," says Natalie Fousekis, a historian and author of Demanding Childcare: Women's Activism and the Politics of Welfare, 1940-1971. "I understand the political forces have prevented it. The studies I have seen and the studies during and after World War Two and today show that investing in good childcare with an educational component to it pays off in all kinds of ways."

If you ask single mothers trying to make it on a low wage job, she says, their biggest concern is childcare. "It adds to the haves and have nots in this country," Fousekis says.

Paying for eggs, but not children

The lack of quality, affordable childcare in the United States heated up since news emerged last year that tech giants Apple and Facebook will pay up to $20,000 for female employees to freeze their eggs if they want or need to delay motherhood.

While many applauded the companies for covering the expensive (and invasive) procedure, it left many uneasy and wondering - if you're going to pay to put a woman's fertility on ice while she helps you make a profit, shouldn't you reconsider your corporate culture to make it easier to be a working mother?

"We offer to freeze your eggs - it's saying how can we fix this now easily and quickly instead of being systematic," says Ariane Hegewisch, a study director at the Institute for Women's Policy Research, who says companies need to do more to help working parents have flexible hours and childcare options. "It's a very technology-centred, short-term approach."

Facebook does offer flexible hours and perks for new parents - but it does not have onsite childcare centres - nor does it have doggie day care as was (widely and falsely) reported since news of the freezing eggs emerged.

The Truman administration planned to yank all the federal funding for childcare after World War Two, which sparked protests across the country, mainly by women. The protest movement failed everywhere but in California where women successfully fought to keep the centres open. But over the years, funding has been chipped away and the California centres decimated.

A child service center in California was equipped to keep children budy and stimulated

At the site of the old Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, there is an exhibit dedicated to the childcare centres at the Rosie the Riveter/WW2 Home Front National Historical Park. Women working in traditional men's jobs during the war were known as "Rosies", often depicted in propaganda posters as a powerful woman in a red bandana welding, driving a truck or flexing her muscles.

Lucien Sonder guides tours at the park (where a handful of Rosies still hold court on Fridays) and says people are often shocked to hear what good services the women had at the shipyards.

"They hired professionals. They were trying to create something that wouldn't just be childcare - they deliberately wanted to call it a Child Development Centre," Ms Sonder says. "They called them at the time eight-hour orphans because many believed these women were abandoning their children for eight hours."

Eleanor Roosevelt was a loud champion of the "perks" and urged companies across the nation to emulate Kaiser's model, with women building combat ships as their children learned ABCs nearby.

"If we do not pay for children in good schools, then we are going to pay for them in prisons and mental hospitals," Eleanor Roosevelt said.

But as women returned home when the war ended, the need for childcare seemed less pressing.

Young parents pick up their child from a DC centre after doing their shopping

In 1975, more than half of all children had a stay-at-home parent, typically the mother. Today, fewer than one-in-three American children have a stay-at-home parent. And parents often cite childcare as their biggest expense and cause of stress. (And a recent rise in the number of stay-at-home mothers is likely partly due to the high cost of childcare for children under the age of five).

Some US employers offer on-site childcare - Amgen and Patagonia are the Kaiser Company Shipyards of today, setting a gold standard in progressive, on-site care, but advocates say that's an anomaly. Hollywood studios and universities and some US government offices also offer on-site childcare centres. But they are not typical - and the centres are often expensive and competitive to get into.

"In the US, we have the cowboy mentality and we're allergic to things that feel like social welfare and it's very counter productive," says Sandra Burud, an author who has studied the cost-effectiveness of on-site childcare. She has advised big companies to build centres to attract and retain employees.

Ms Burud says it's a mistake to frame corporate or government-funded childcare as a "perk" and that it should be a staple of the workforce.

"You shouldn't think of it as a benefit. It's like having a parking lot or having a cafeteria - not every one uses it - but it's a tool for the business," she says.