The men of steel with a softer side

- Published

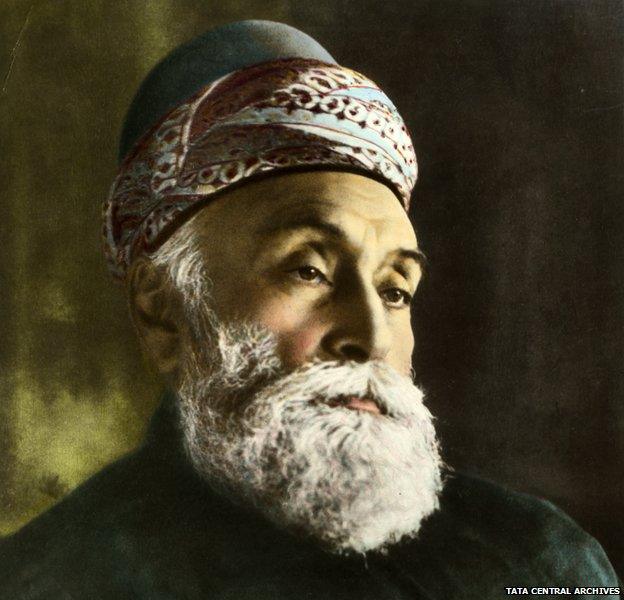

Tata, the Indian company that owns Tetley Tea and Jaguar Land Rover, prides itself on its ethics - 66% of the business is owned by charities. Its unique character was shaped by the passions of its founder Jamsetji Tata and his successors.

Towards the end of the 19th Century, Indian businessman Jamsetji Tata walked into one of Mumbai's most expensive hotels - but, so the story goes, he was told to leave because of the colour of his skin.

Legend has it that he was so incensed he decided to build his own hotel - a better one that would welcome Indian guests.

And so, in 1903, the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel opened its doors on the waterfront in Mumbai. It was the first building in the city to have electricity, American fans, German lifts and English butlers. It's still the height of luxury today.

Jamsetji was born in 1839 into a Parsi family - many of his forefathers had been Zoroastrian priests. He had made his fortune trading cotton, tea, copper, brass and even opium, which was legal at the time. He was well-travelled and fascinated by new inventions.

The Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in Mumbai circa 1920

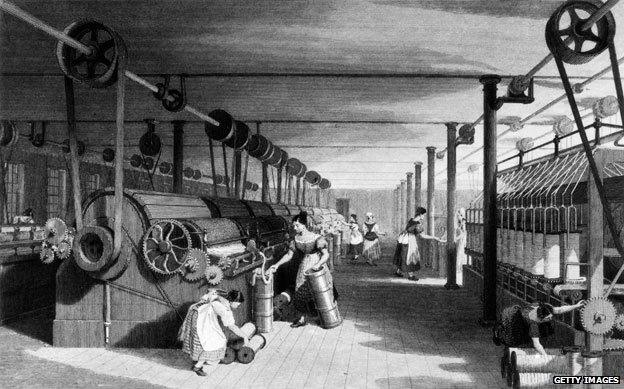

On a trip to the UK he had spotted the potential of the Lancashire cotton mills. He realised India could compete with its colonial masters and in 1877 set up one of the country's first textile mills. Empress Mills opened on the same day that Queen Victoria was crowned Empress of India.

Jamsetji had a vision for India summed up by the Hindi word Swadeshi, which means "made in our own country" - an idea that was part of the Indian independence movement of the early 1900s.

"What advances a nation or a community is not so much to prop up its weakest and most helpless members, but to lift up the best and the most gifted, so as to make them of the greatest service to the country," he said.

His biggest dream was to build a steel plant, but he died before he could realise this goal.

His son Dorab took on the challenge and when Tata Steel began production in 1907, India became the first Asian country with a steel plant of its own.

A sceptical British official scoffed that he would eat every ton of steel they produced, but when World War One broke out Tata provided the steel for railway extensions that were crucial for the British campaign.

Jamsetji also left instructions for a model industrial town to be carved out of the jungle for the workers. He was very specific: "Be sure to lay wide streets planted with shady trees, every other of a quick-growing variety. Be sure that there is plenty of space for lawns and gardens. Reserve large areas for football, hockey and parks. Earmark areas for Hindu temples, Mohammedan mosques and Christian churches," he wrote in a letter to Dorab.

Textile workers in a British cotton factory circa 1840

A view of Tata Steel at Jamshedpur

The result was Jamshedpur. UK Business Secretary Vince Cable visited 50 years ago and, in a recent speech, remembered it as an "absolutely remarkable place… a citadel of steel-making in a country that was only just beginning industrialisation".

From the outset, and before such things were legally required anywhere in the world, the Tatas showed commitment to labour welfare introducing pensions (1877), the eight-hour working day (1912) and maternity benefits (1921) for their employees.

It was all down to Jamsetji's belief that business is sustainable only when it serves a larger purpose in society. "In a free enterprise the community is not just another stakeholder to business, but is in fact the very purpose of its existence," he said.

He funded the creation of the Indian Institute of Science at Bangalore to ensure the country could provide engineers and scientists to realise his ambitions.

He and his sons bequeathed much of their personal wealth to charitable trusts, which still own 66% of the central Tata holding company, Tata Sons.

This has had a lasting impact on the way the business operates, planning for the long term rather than quick, short-term profits.

Tata has helped thousands of people through its social outreach work

The family still owns 3% of the shares, and the rest belong to various companies and shareholders.

This increases trust in the firm, says Jerry Rao, a business analyst in Mumbai. "The fact that everybody knows that most of the shares are held by trusts and not by individuals who are fattening themselves, that helps.

"Because they are not a large family, they tend to treat their professional managers well, as colleagues, as interested parties, rather than purely as family retainers," he says. "And the Tatas who are around tend to lead relatively simple lifestyles."

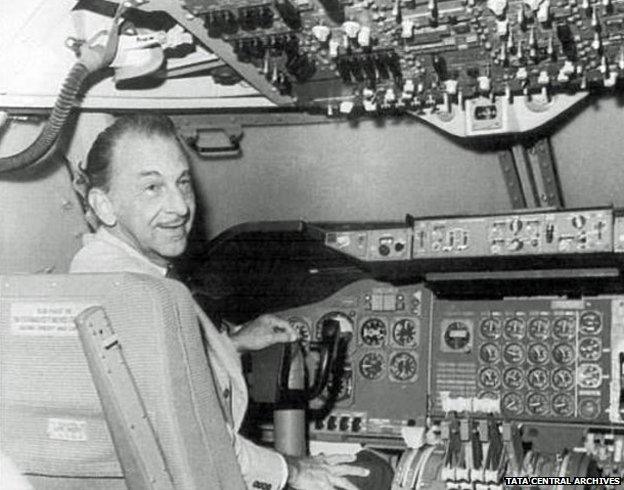

Another member of the extended family, Jehangir Tata, also known as JRD, became chairman in 1938, when he was 34, and remained at the helm for half a century.

He hadn't planned on becoming an industrialist. His dream was to be a pilot, an obsession that began when he met Louis Bleriot - the first man to fly across the English Channel - and watched his aerial acrobatics over the beaches of northern France.

JRD was the first person to qualify as a pilot in India, at the Bombay Flying Club - his licence bore the number 1, something he took great pride in.

In 1930 he tried to become the first Indian to fly solo between the UK and India. He might have won the race, had he not helped out a stranded competitor with some spark plugs. As a result of his generosity, JRD lost the race by a few hours.

Two years later he set up and personally flew India's first air mail service, occasionally carrying a single passenger on top of the mail bags. There were no runways so the planes would take off and land on mudflats.

The mail service evolved into India's first airline, Tata Airlines, later renamed Air India which was a great success. For a while it was jointly owned by the state, but in 1953 the government decided to nationalise the country's airlines.

JRD was invited to head the international side of the operation and was chairman of Air India until 1978. Staff remember his insistence on perfection - he sent them endless memos about the smallest details.

There was more to come though. As the information age dawned, JRD again took aim at an industry associated with the most advanced economies. He started up Tata Consultancy Services in 1968, computerising company paperwork.

It was a rare example of innovation at a time when much of the Indian economy was stifled by central planning and regulation. Today TCS is the most profitable company in the whole Tata Group, supplying computer software and processing around the world.

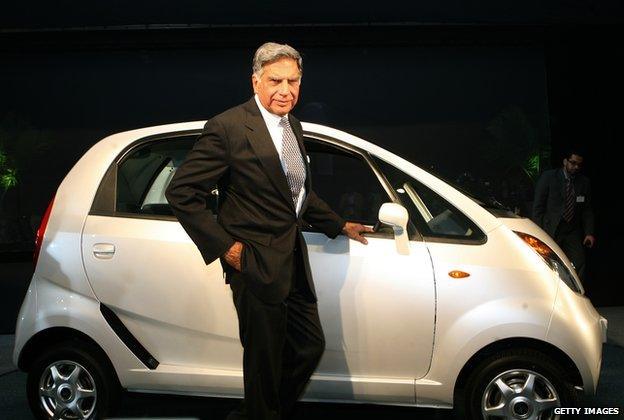

In 1991, JRD, was succeeded by his distant cousin, Ratan Tata. This coincided with the Indian government relaxing the state's control over the economy, and Ratan went on a global shopping spree.

Tata bought Tetley Tea, set up a joint venture with the insurance company AIG, acquired the Ritz-Carlton in Boston, Corus Steel in Europe and Daewoo's heavy vehicles unit.

As one manager put it, you can find Tata almost everywhere: "From tea to IT."

Tata became the biggest business in India but compared with other Indian business magnates, the Tatas themselves have always been remarkably modest.

JRD lived in a rented house near the company headquarters in Mumbai, and Ratan drove himself to work - or insisted on sitting next to his driver.

In 2009, Ratan fulfilled a long-held dream when he created the cheapest car in the world, external - the Nano - which went on sale for 100,000 rupees, (£1,000, $1,600). Sales were disappointing though, and Ratan didn't achieve what he had hoped to do - to replace the motorcycle with something safer but affordable.

Ratan Tata with the Tata Nano when it was launched in Delhi

On average, the Tata Group and the Tata Trusts contribute about $200m (£130m) per year to social causes.

Tata Steel has charitable trusts that run rural development projects in the tribal areas surrounding Jamshedpur, which is located in the state of Jharkhand, formerly part of Bihar. They offer microfinance and literacy classes for women, and there is even a project to keep traditional tribal music alive.

The company plays on its reputation - one of its ads jokingly boasted: "We also make steel!"

Nevertheless, the increasing industrialisation of Jharkhand has raised environmental concerns. Journalist Divya Gupta is worried about pollution in Jamshedpur's main river.

"I think it would be unfair to lay all the blame on Tata's doorstep, but certainly in Jamshedpur, it's the main industrial unit," she says. When she raised the issue with Tata Steel, she claims the company replied: "The rivers are not ours." She was disappointed. "It was a rather defiant sort of response. It was not one I was expecting, certainly in the tradition of [their] concept of giving back to the community."

There are concerns about river pollution in Jamshedpur, now home to several industries

But Tata's chief ethical officer, Mukund Rajan, defends the company's record. "You can't operate in the chemicals industry or the steel industry and mining without having an obvious impact on the environment," he says. "So the question is how do you mitigate the worst impact?"

For example, Rajan says the company keeps water usage to a minimum around its chemical plants, and Tata Steel "will show you mines where they have completely restored the fauna and flora of what was a mining activity that had diminished the support capability of the soil and they've restored it and revitalised it."

And there was more controversy when, following the global downturn, Tata announced it was in talks to sell large parts of its European steel operations. Unions in the UK accused Tata of not being true to their values. In response, the chairman flew over from India and promised not to sell without further consultation.

As Mukund Rajan points out, without a profitable business none of the other benefits can exist. "I'd say value and values are both inextricably linked for Tatas," he says. "Without creating economic value we cannot support the values we stand for."

In December 2012 Ratan handed over leadership of the company to a non-Tata, Cyrus Mistry - although there is a family link through marriage.

The motto of the Tata business empire remains the Zoroastrian creed: Humata Hukhta Hvarshta - which means: good thoughts, good words, good deeds. But the bigger the business grows, the more difficult this becomes.

Historian and Tata family friend Zareer Masani presents Tata: India's Global Giant on Tuesday 3 February on BBC World Service and on BBC World News on Saturday 7 February at 09:10 and 20:10 GMT. You can also catch it on BBC Radio 4 on Friday 6 Feb at 11.02 GMT.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.