Brian Williams and the decline of the US news anchor

- Published

- comments

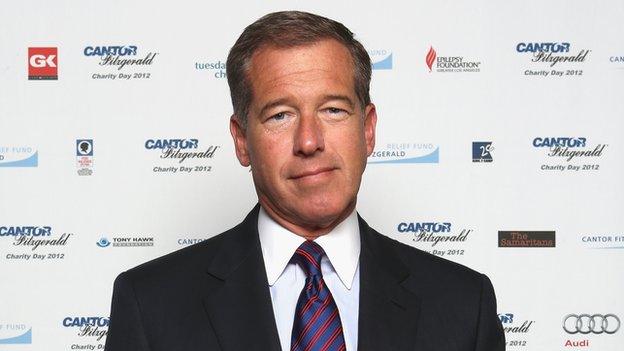

NBC's top news presenter Brian Williams has apologised for the "mistake"

Usually it's in late night bars that journalists are prone to exaggeration. But fabricating a story on a late-night talk show, and then repeating it, has landed Brian Williams in trouble.

Appearing on the David Letterman show in 2013, he told a riveting story from the Iraq war of how his helicopter was forced down after being hit by a rocket propelled grenade.

Last week, on the NBC Nightly News, he repeated the story again, with graphic pictures of the incident.

The trouble was that Williams was not on board the damaged helicopter, and now it's his reputation that is incurring collateral damage after an embarrassing on-air apology.

To journalists tempted to embellish their war stories, this is a cautionary tale. At a time when late-night satirists are usurping primetime news presenters, it also shows the dangers of ridiculing yourself.

Were an American television network to build a news anchor from scratch, I have long thought they would come up with someone like Williams.

Dashing of looks and slick of presentation, it seemed somehow preordained that he would one day inherit the chair left vacant by the NBC News legend Tom Brokaw in 2004, and also the multi-million dollar pay packet that went with it.

Tom Brokaw and Dan Rather, two pillars of yesteryear

Brokaw also presented NBC's morning show in the early 80s

Television executives doubtless looked upon him as a figure of continuity: an identikit anchor who would prolong the winning formula of big evening news ratings and huge advertising revenues.

However, he came to occupy that seat at the very moment when the media industry was going through a period of immense and bewildering change.

Even before this unfortunate "memory lapse", the standing of network news anchors and what were once their "must-watch" bulletins was in decline.

Just consider the viewing figures. In 1985, the nightly network shows were watched by an average of 48m viewers. By 2013, that figure had pretty much halved, to 24.5m.

Why wait until 6.30 in the evening, when continuous news channels, websites and platforms like Twitter make it available in real time? Why rely on the three major TV networks when there is now a multiplicity of media?

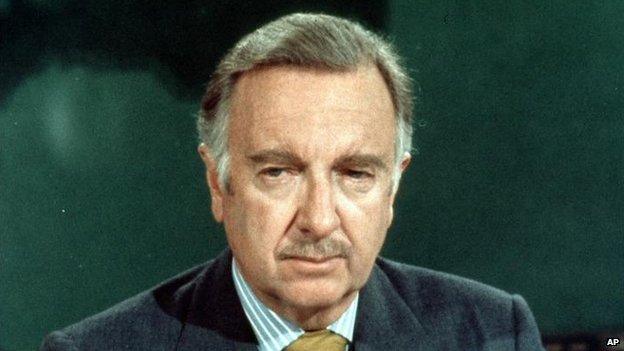

Or ponder the declining public profiles of the major presenters, their dwindling authority, too. Walter Cronkite of CBS News was often called "the most trusted man in America."

So much so, that his sceptical reports from Vietnam after the Tet Offensive in 1968 marked a turning point on the home front. "If I've lost Walter Cronkite, I've lost Middle America," Lyndon Johnson was supposed to have lamented.

Walter Cronkite was known as the "most trusted man in America"

Cronkite was a giant amongst giants - Chet Huntley, David Brinkley and John Chancellor.

Their heirs, Tom Brokaw, ABC's Peter Jennings and Dan Rather of CBS News, were also commanding figures. Anchors were a constant and reassuring presence in the living rooms of America.

By contrast, a study last year suggested that just 15% of viewers under the age of 30 could identify Brian Williams. To the younger generation, his daughter, the actress Allison Williams, who plays Marnie in the hit HBO comedy Girls, is probably a more recognisable figure.

For younger viewers especially, the big three anchors have been usurped by Jon Stewart of The Daily Show.

A much-quoted online poll conducted by Time magazine in 2009 revealed, astonishingly, that 44% considered the comedian to be the best source for trustworthy news. Williams scored 29%. More than five years on, that poll does not look quite so outlandish.

Jon Stewart has hosted his comedy news programme for 15 years

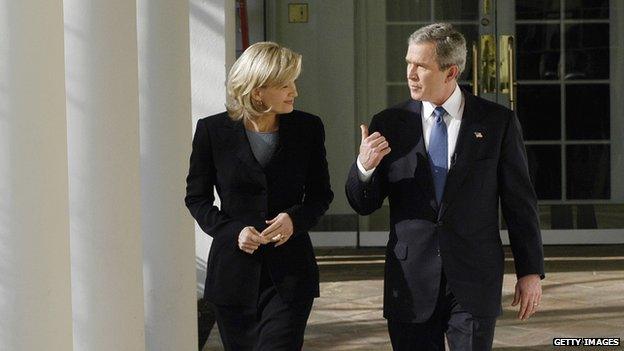

A milestone moment in TV news came late last year when ABC picked the successor to its highly respected anchor, Diane Sawyer.

It announced that the former Clinton aide George Stephanopoulos would be the network's lead anchor, but continue to present its top-rated breakfast show, Good Morning America.

Upending the traditional hierarchies of television news, it selected a lesser-known figure, David Muir, to front the primetime show.

With the Williams imbroglio, a few modern-day media trends intersect. It not only illustrates the diminished standing of network news anchors, but the rise of social media, like Facebook and Twitter, which enable everyday viewers to challenge and correct major news organisations.

After Diane Sawyer left the top job at ABC, the role's prominence lessened

Facebook was where Williams' fabrications were found out. "Sorry dude, I don't remember you being on my aircraft," complained flight engineer Lance Reynolds, when NBC posted a video of Williams made-up story online.

Other veterans, who also knew the story, weighed in on Twitter.

Inevitably, a hashtag #BrianWilliamsRemembers quickly followed, with hilarious results. This kind of online shaming, the digital equivalent of the medieval stocks, is very much a recent phenomenon.

Doubtless this will come to be seen as a modern-day media parable - the story of an anchor who lost his compass.

- Published5 February 2015

- Published5 February 2015