A time capsule of the BBC at Alexandra Palace?

- Published

Almost 80 years ago the world's first regular television service was launched by the BBC from Alexandra Palace in north London - known as Ally Pally. Those original studios have lain empty since the last programme-makers left in 1981. Now a £27m plan to turn them into a visitor attraction is sparking controversy.

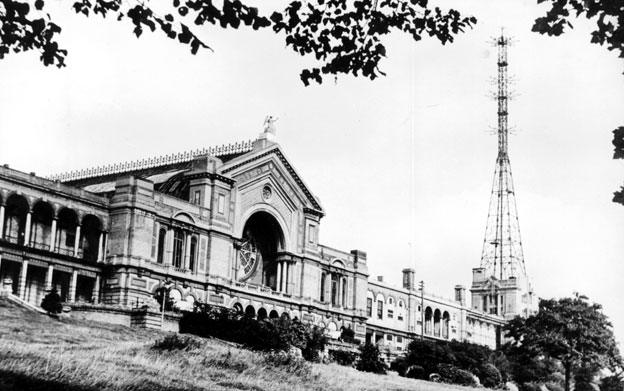

Perched on top of one of London's highest hills is a giant Victorian people's palace - a place where history was made.

Today most of Alexandra Palace is a thriving venue for concerts and exhibitions, but the eastern end is underused and decaying, beneath the great transmitter mast installed by the BBC and perched atop one corner.

There's an ice rink, popular with local people. There's a cavernous Victorian theatre, still with its original wooden stage machinery, which has lain dark for more than 60 years. And then there's the wing where in 1936 the world's very first proper television service started, and where some television programmes continued to be made up until 1981.

Today those old studios are derelict and an asbestos-ridden safety risk. But the trust that runs the palace and its surrounding park has an ambitious £26.7m refurbishment plan which would see the theatre brought back into use and the old studios turned into a BBC Experience, a visitor attraction celebrating Ally Pally's central role in the development of television broadcasting. The plan has the support of the BBC, and a provisional £19.4m in funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

But first the trust has to to get planning permission on Monday from Haringey Council, which also happens to be the palace's ultimate owner. And it has to overcome the opposition of campaigners, who believe the plans for the old studios would mean destroying the very things that make the palace so special.

It's a debate which raises wider questions about how best to preserve and open up historic places where little of what made them historic still remains.

The BBC took over its corner of Alexandra Palace in 1935 and spent a year converting it for the new medium of television. It built offices with Art Deco bay windows in one of the corner towers, constructed the mast on top, and installed powerful transmitters in the basement. The two studios were converted high-ceilinged Victorian dining rooms, and each was equipped with quite different technology.

In one, the cameras were electronic, made by Marconi-EMI. In the other, the BBC installed cameras and kit which used the much more cumbersome system devised by the television pioneer John Logie Baird.

In theory, the two systems were to broadcast programmes in alternate weeks for a six-month trial - in fact, the Baird system was quickly scrapped. It had become clear that his television method - which depended on shooting programmes on film which was then instantly developed and scanned to provide an almost-live transmission - offered far less flexibility than the Marconi-EMI alternative.

Those early programmes were a hotch-potch - variety shows (with a resident band), plays, gardening demonstrations, occasional outside broadcasts. The audience was tiny - a few thousand homes within reach of the transmitter in the London area. And the rest of the BBC looked down on this eccentric upstart. After all, it was BBC radio that had the prestige, the central London headquarters and the massive audiences.

Michael Aspel in the BBC studio

The television service shut down in 1939 at the outbreak of World War Two, and restarted in 1946. Yvonne Littlewood, later a distinguished light entertainment producer, was one of the post-war pioneers. "It was very challenging because there was nobody to actually tell you what to do. You were secretary to a producer and there were just the two of you, and you made it up as you went along.

"It was exciting, yes, but more in retrospect than at the time - you didn't have time to think about it. You just had to get on and learn as fast as you could." Her boss had worked in sound effects in BBC radio before wartime service in the Free French navy - a background not untypical of those early programme-makers.

Patricia Bath, hostess of the weekly television magazine programme Picture Page, with a lighting engineer

American actress Lizabeth Scott appearing in Picture Page

It wasn't until the coverage of the 1953 Coronation that television came of age, with households across the country rushing to buy sets and the audience slowly beginning to overtake that for radio.

As television technology advanced the two Alexandra Palace studios were periodically refurbished and re-equipped. As early as 1956, the BBC was experimenting with colour television there. In due course, most television production moved to Lime Grove studios in Shepherds Bush and then the BBC's new Television Centre. But television news continued to come from Ally Pally until 1969. The last programme-makers on the site worked for the Open University until their departure for Milton Keynes.

Since 1981, the old studios have been locked up, quietly rotting. Today Studio A is in reasonable condition, filled with old television sets and mannequins operating mock-ups of 1930s equipment, left over from a previous attempt to create a broadcasting museum on the site. A post-war lighting gantry spans the space. The only element that survives from 1936 is the window of the producer's control gallery, high up in one corner, which is listed as of historic interest.

One of the old BBC offices

But Studio B and the hotchpotch of corridors and rooms around it are in a terrible state - flaking walls, collapsed ceilings and dead pigeons on the floor.

Duncan Wilson, Alexandra Palace's chief executive, says the refurbishment plan would involve retaining some historically significant bits of the building - including that producer's gallery and the large wooden scenery doors with porthole windows into the studios - but remodelling the rest of the space.

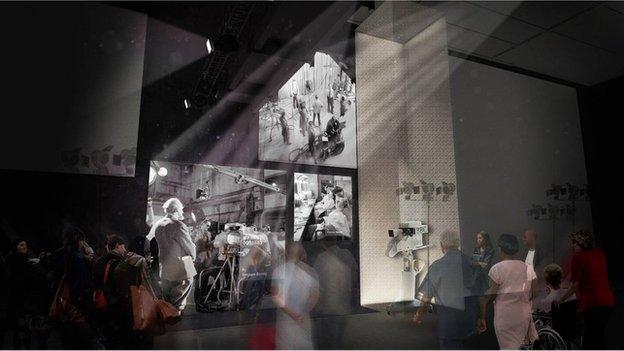

After an introductory film telling the story of popular entertainment at Alexandra Palace, leading up to the birth of television, visitors would enter the old Marconi-EMI studio. "You're brought through to Studio A, where it happened," he says, "and Studio A is gradually revealed to you through a series of curtains, using sound and light and images and audio-visual presentation, dramatically using real characters to tell the story of the competing technologies, and the amazingly cobbled-together but dramatic moment when they began to broadcast, and beyond into colour television and all the things that happened here."

There would be a display of old equipment borrowed from the National Media Museum in Bradford, but there wouldn't be any attempt to recreate the appearance of the studios in 1936, because that could never be authentic. Too little remains.

The proposed entry for the main part of the building features a staircase that doubles as an auditorium

Large screens will show film in the old studios

"What we've got left is the place and its basic dimensions," Wilson says. "We've been accused of creating a black box. Well the studio was a black box, and we're putting it back to being a black box and we are doing it in a way that is sympathetic, but we're not faking it up to look like it was in one moment in 1936."

But critics of the plans aren't convinced. Stephen Games lectures in both architecture and media history. "We're talking about the equivalent of a World Heritage Site," he says. "A lot of people from around the world are going to want to see it, and what they'll want to see are the studios themselves. But you won't be able to see them because they're going to be wrapped up in partitions, covered in video screens and filled with display cases.

"There's an essential difference between a museum and the place itself. In a museum you have an empty box and you fill the empty box - here the place itself is the exhibit."

Others agree. The local conservation area advisory committee says the proposals "would obliterate any last vestige of period atmosphere of the spaces as they are now". One objector calls the proposals "an audio-visual pastiche". Another says: "The Heritage Lottery Fund should not be used to destroy heritage."

The critics are particularly incensed at one aspect of the plan. In 1936, the BBC bricked up parts of a colonnade that runs along the entire front of the building at second floor level. Alexandra Palace wants to take out the brick infill to restore the building to something close to its original Victorian appearance.

"This is the equivalent," say the protesters, "of knocking down the Nissen huts at Bletchley Park because they ruin the view of the Victorian mansion in the grounds of which they were built, and showing what they used to look like on video monitors."

But the plan has its supporters too. In their comment on Alexandra Palace's planning application, Stephen Greenberg and Rachel Morris, local residents and experts in planning and designing museums and exhibitions say: "If you restore the studios and represent them as 'found space', they will appeal to a very small specialised audience. They will open a few hours on a few days, rely on volunteers to run them and in all probability end up being mothballed."

Any visitor attraction in the old studios, they say, needs to appeal to a diverse audience, including young people - a sentiment Duncan Wilson would endorse.

And they make one other point that all those involved can agree on, even if they differ on the proper way to exploit it. "What makes the story so incredible is that it began here, in this space - and changed the world. This is the kind of storyline museums dream of."

Fires and filming - a history

First opened in 1873, but it was destroyed by a fire after just 16 days

In May 1875, less than two years after the destruction of the original building, a new palace opened

In 1935 the BBC leased the eastern part of the building from which the first public television transmissions were made in 1936

In July 1980, the building caught fire for the second time - the Great Hall, Banqueting Suite, and former roller rink together were destroyed. Only Palm Court and the area occupied by the BBC escaped damage

Development and restoration work began soon after and the Palace was reopened in March 1988

Source: www.alexandrapalace.com

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.