What happened to the Qatar World Cup's cooling technology?

- Published

A Fifa taskforce has recommended the Qatar World Cup takes place in November and December 2022. Previously it was claimed pioneering cooling technology would allow it to happen in the summer. So what has changed?

When the shock announcement came through that a tiny gulf emirate would host the world's biggest sporting tournament, there was one question everybody asked.

How would they cope with the heat?

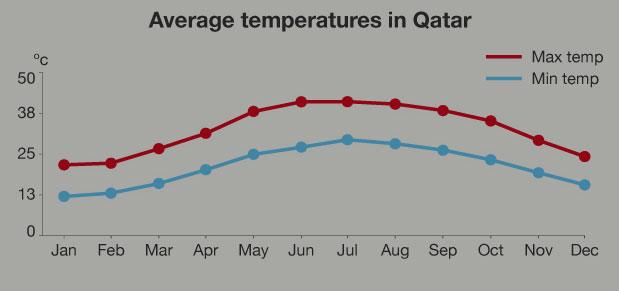

The World Cup is typically held in the middle of the year, when Qatar is searingly hot. Average high temperatures in Doha in June are 41C (106F) and it can get close to 50C.

These are far from ideal conditions in which to hold a football competition. Fifa's own evaluation , externalof Qatar's bid to stage the event said the heat "has to be considered as a potential health risk". A technical report described a summer tournament as "high risk".

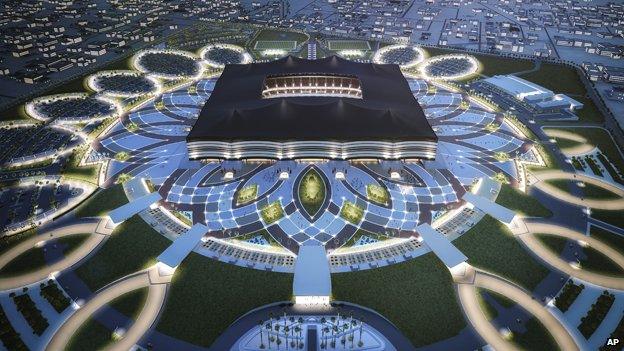

Artist's impression of the Al Wakrah stadium

But the organisers said they had a solution. During the bidding process, Qatar promised advanced air-conditioning technology that would cool stadiums, training pitches and fan zones to 23C. A 500-seater prototype stadium called the Qatar Showcase, external, designed by British firm Arup, was built to demonstrate how the system might work.

It helped secure the bid. And whenever scepticism was expressed about the technology, which has never been used on such a scale, Qatar's World Cup organising committee insisted the games would go ahead in summer, chilled as promised.

Now, however, a Fifa taskforce has recommended that the event takes place in November and December. In a statement, external, it cited the "consistently hot conditions" that prevail in the peninsula during the summer months.

With major European league seasons thrown into chaos, it's the latest scandal to hit a tournament already bedevilled by allegations of corruption, external and abuse of migrant workers.

Artist's impression of the Al Bayt stadium

It raises the question - if the cooling technology will be so effective, why is the tournament being moved?

Even though the new air conditioning systems are no longer needed, the hosts say their development will go ahead regardless. Hassan Al Thawadi, head of the Qatar 2022 World Cup organising committee, has insisted: "Whenever the World Cup is hosted, we're still moving ahead with the cooling technology for the legacy that it offers."

There has long been scepticism, external about whether it could be done.

In 2011 architect John Barrow, who is designing the Sports City stadium in Doha, one of the proposed World Cup venues, said, external he was "fighting hard" to persuade organisers to drop its cooling technology plans which he said were "not good from a long-term sustainability point of view".

The world players' union FIFPro also called, external for the tournament to be moved to winter on health and safety grounds.

Qatar's Showcase had, however, offered a demonstration of how it could be achieved, albeit on a much smaller scale.

It used solar panels outside to collect energy from the sun. This was used to power an absorption chiller to chill the water, which was kept at 6C. The chiller's output was stored using "phase change materials, external" and used to cool air before it was blown through the stadium, maintaining pitch temperatures below 27C. Perforated seats allowed the cooled air to flow and a canopy roof rotated to provide shade.

Artist's impressions of the Lusail Iconic Stadium, where the first and last games of the tournament will be held

"Basically, you use the heat to produce cold," says Graeme Maidment, professor of air conditioning and refrigeration at London South Bank University. "It's doable. But it's going to be very, very expensive. It's going to use lots and lots of kit."

The difficulty in doing this on a bigger scale would come when it came to meeting Fifa's environmental requirements, Maidment says. The stadiums might be carbon neutral in terms of the energy used, he adds. But it would be much more challenging to achieve carbon neutrality when producing all the equipment required is taken into account.

In 2013 the organisers said, external they would either create a central solar power farm or have separate ones built at each of the event's 12 stadiums. Air would be pumped to the "spectator ankle zone" and the back and neck area of the seats, Qatar 2022's technical director Yasir Al Jamal promised, external.

Scaling up the miniature showcase into a series of major stadiums would be an ambitious proposition. Maidment says: "It's a big project but engineers are used to dealing with big projects."

But it doesn't appear to be the feasibility of the proposed cooling system, or otherwise, that convinced Fifa that a summer event was undesirable.

In fact, even without air conditioning, Qatar's heat is "something that the vast majority of players could adapt to", says Carl James, who works at the Environmental Extremes Laboratory run by Brighton University's sports science department.

Well-conditioned athletes are, in theory, capable of competing at high temperatures, he says. The Marathon des Sables is held in 50C heat in the Sahara Desert. The "Heatstroke Open", which claims to be the world's hottest golf tournament, takes place in similar conditions in California's Death Valley. The 1934 World Cup final between Italy and Czechoslovakia in Rome saw temperatures surpass 40C.

They would have to be given time to acclimatise and would need to be carefully monitored by medical professionals, James says - although the football wouldn't be much of a spectacle, with players making quick, short passes and avoiding long runs to preserve energy. It would effectively be football in slow motion.

"But the bigger safety concern is for the fans," James says. Outside the stadiums, it would be much harder to maintain the safety of thousands of spectators - many of whom would be drinking alcohol, thus dehydrating them further - in the scorching heat.

It seems this perspective was shared among Fifa's upper echelons. "You can cool down the stadiums but you can't cool down the whole country," said, external the organisation's President Sepp Blatter.

Fifa medical chief Dr Michel d'Hooghe has said he did not doubt the Qataris could organise a tournament where teams could play and train in a stable, acceptable temperature, "but it's about the fans". He added: "They will need to travel from venue to venue and I think it's not a good idea for them to do that in temperatures of 47C or more."

Despite the organisers' insistence that their air conditioning plans will go ahead, exactly what lies in store is unclear. Arup, which is providing consulting services for Qatar 2022's stadium cooling design, refused to comment when approached by the BBC.

Either way, it's unlikely to be the last row in what is shaping up to be the most controversial World Cup in history.

More from the Magazine

Life without artificial cold is hard to imagine in the developed world. But it all started 200 years ago with some giant ice cubes. The chilling story of the men who changed our lives forever by cooling us down, by Steven Johnson:

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.