Crossing the Forth without the Forth Bridge

- Published

The Forth Bridge is one of the world's most recognisable landmarks. It was a milestone in engineering history when it opened 125 years ago. In addition, there have been numerous attempts to traverse the waters between Edinburgh and Fife - many of them ingenious, others downright bizarre.

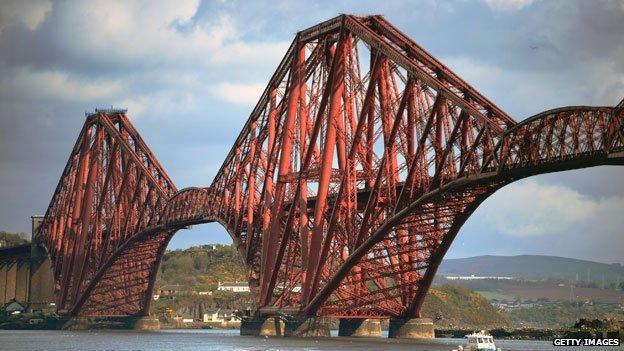

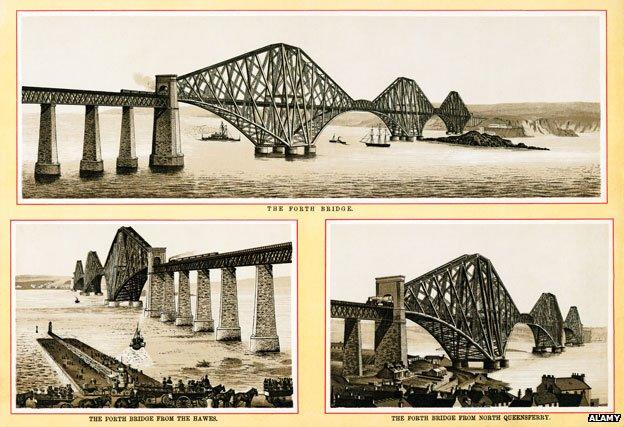

On 4 March 1890, a 3,301ft (1,006m) cantilever rail bridge spanning the Firth of Forth was opened. It was a hugely significant technical feat and today remains an icon of Scotland.

The Forth Road Bridge followed in 1964 and another, the Queensferry Crossing, is currently under construction.

But there have been many other schemes for getting across the estuary. Some of them have been successful, others less so.

Tunnel

Since the 17th Century there have been attempts to tunnel beneath the Forth.

Sir George Bruce, a coal merchant from Carnock, Fife, mined a seam beneath the estuary which emerged at an artificial island a mile out, from which coal was loaded on to ships. According to some accounts, King James VI and I was invited to see it for himself in 1617. He took fright and accused Sir George of luring him into there to kill him. The mine's tunnels were later flooded.

Subsequently, plans to a build an underwater link between the north and south sides were discussed in the 1790s, in 1805 and 1891, but never got off the drawing board.

In 1954, plans for a £5.3m "Forth Tube" - a 2,800ft reinforced concrete tunnel which traffic would pass through - attracted support but were ultimately rejected in favour of the Forth Road Bridge.

Eventually, in April 1964, a crossing was completed, external 500 metres below the Forth, when miners from the Kinneil colliery on the south shore broke through a tunnel to meet co-workers from the Valleyfield colliery to the north.

The idea was that coal extracted in Fife could be processed at the more modern Lothian site, but Kinneil was closed in 1982 and the tunnel has been sealed.

The new Forth crossing is now under construction

There were calls, external for a tunnel linking Edinburgh and Fife to be built when it emerged the existing Forth Road Bridge was deteriorating. But the Forth Replacement Crossing Study concluded in 2007 that a bridge would be significantly cheaper, paving the way for the Queensferry Crossing.

Boat and hovercraft

Boats have crossed the firth since at least the 6th Century, says Lillian King, author of Building the Bridge. "Both politically and economically it's very important," she says. In 1130 the Church set up a regular ferry service between North and South Queensferry for pilgrims heading north to St Andrews.

It was used by Mary Queen of Scots, most famously after her escape from Loch Leven Castle.

Traffic soared during the industrial revolution and in 1821 a steamboat service was introduced. In 1850 a "train ferry, external" began sailing between Granton and Burntisland. It allowed rail wagons to roll directly on to the vessels and was the world's first roll on/roll off rail ferry.

A trial hovercraft service between Kirkcaldy and Portobello in 2007

More recently, transport company Stagecoach attempted to introduce a hovercraft service, external between Kirkcaldy and Portobello. Some 32,000 passengers used the 20-minute route during the fortnight-long trial in 2007, but Edinburgh City Council refused planning permission for a terminal.

Pontoon bridge

Some scholars have speculated that the Romans may have built a floating bridge made from boats across the firth during the reign of Septimius Severus. A coin issued in 209 AD depicts a pontoon bridge which historians believe may have commemorated a military campaign in Scotland.

It's been suggested, external that the most likely location for this would have been Queensferry - roughly where the Forth Bridge sits today - with the island of Inchgarvie acting as a halfway point.

Such a bridge would have been within the technical capabilities of the Romans. However, there is no conclusive proof that it was located at Queensferry. Other theories, external put the boat bridge on the river Carron or further up the Forth at Stirling.

Other bridges

The idea of building a permanent bridge across the Forth was seriously discussed as far back as 1740. In 1818 an Edinburgh civil engineer and surveyor named James Anderson produced a design for a suspension bridge made of 2-2,500 tons of wrought iron.

Later engineers considered the plans dangerously flimsy. In 1890, a historian said, external it would have had a "very light and slender appearance, so light indeed that on a dull day it would hardly have been visible, and after a heavy gale probably no longer to be seen on a clear day either".

In 1863 the North British Railway, and the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, commissioned designs for a railway bridge. Engineer Thomas Bouch drew up plans for a single-track bridge further up the Forth at Charlestown but these were eventually abandoned.

Plans for a crossing were revived in 1873 when the North British Railway gained authority to build a bridge across the Firth of Forth, roughly at the site of the present rail crossing. It was designed by Bouch and construction began in 1878.

But the collapse of the Tay Bridge, external, which had also been designed by Bouch, the following year led to this project being scuppered.

Fears about a repeat of the disaster meant that engineers gave the eventual Forth Bridge a "belt and braces" design, says rail expert Christian Wolmar, which accounts for its arresting visual appearance: "If it had looked like the Tay Bridge it would not have the same grandeur."

Hot air balloon

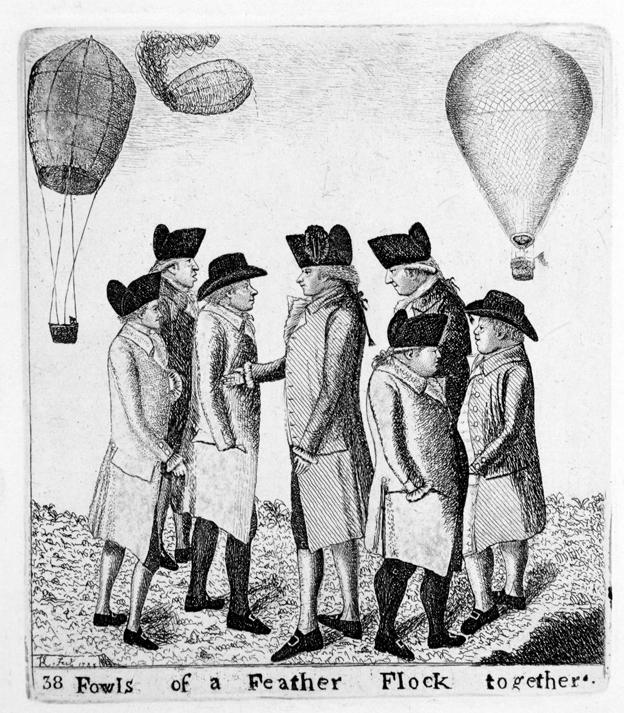

Contemporary drawing of Vincenzo Lunardi in Edinburgh for his balloon flight

On 5 October 1785, an Italian named Vincenzo Lunardi took flight from George Heriot's school in Edinburgh in a hot air balloon, and the wind carried him across the Forth.

Although it was not quite Scotland's first balloon journey - Forfar-born James Tytler briefly took flight, also in Edinburgh, the previous August - it was a spectacular voyage.

As he flew above the Forth, Lunardi later wrote, external, he could see as far west as Glasgow and Paisley "as well as all those on both sides of the Forth, the meanders of which, with the highways and rivers in the adjacent country, had exactly the same appearance as if laid down on a map".

He landed 46 miles away in Coaltown of Callange near Ceres, Fife, and today a plaque marks the spot. Hot air ballooning did not catch on as a means of crossing the Forth, but balloon-shaped "Lunardi bonnets" became fashionable among Scottish women - such a garment is mentioned in Robert Burns' poem To A Louse, external.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.