The schoolboy sailors who died at Gallipoli

- Published

HMS Goliath

Much has rightly been written of the boy soldiers who were able to lie their way into serving and dying on the Western Front. But what about the schoolboy sailors deliberately sent to war, writes Andrew Thomson.

The 100th anniversary of the Gallipoli landings - one of the costliest phases of World War One - will be commemorated next month. It's estimated that both sides lost 130,000 dead as the Allies unsuccessfully battled the Ottoman army for control of the Dardanelles strait.

Among the dead were two 15-year-old boys from Scotland - best friends Torquil MacLeod and Ronnie Faed, who served aboard the Royal Navy battleship HMS Goliath.

Both Torquil and Ronnie came from privileged backgrounds.

Born on 11 September 1899, Torquil was the second son of Roderick and Alice MacLeod of Cadboll. The childhood home he shared with his two brothers and sister was Invergordon Castle, a now demolished stately home.

Torquil MacLeod and Ronnie Faed

Ronnie Faed was born on 29 May 1899, the son of the Scottish artist James Faed Jr. Ronnie's family were constantly on the move because of his father's work commitments but they considered Galloway to be their home.

Like most boys of their social class Torquil and Ronnie were sent off to preparatory boarding schools. They probably first met at the age of 12 when they both enrolled at the Royal Naval College at Osbourne on the Isle of Wight in the summer of 1912.

The two cadets completed two years of officer training there before moving on to the college's senior campus at Dartmouth.

Discipline was strict for the trainee officers. There was constant military drill and they had compulsory "cold plunge" washes at 6am every day.

They were also given intensive lessons on engineering and other practical skills that would be of use for life aboard a Royal Navy ship.

However, Torquil and Ronnie, along with the rest of their class-mates, also got plenty of opportunity to enjoy sports and were particularly encouraged to become strong swimmers.

1910: Naval cadets receiving swimming lessons

Their routine was turned upside down on 1 August 1914 when 434 cadets of the Dartmouth cadets aged between 14 and 16 were ordered to mobilise and join the Royal Navy's reserve fleet.

One of the cadets Wolston Weld-Forester, who survived the war, later wrote that on hearing the news they all rushed towards the main college building, joyous at the thought of the adventures that lay ahead.

"Already an excited crowd was surging through the grounds - some with mouths still full from the canteen, others clutching cricket pads and bats and yet others but half- dressed, with hair still dripping from the swimming baths..."

But while mobilisation was a source of joy for the cadets it undoubtedly caused anxiety among their parents and for some their worst fears were soon realised.

By mid-November at least 23 of the youngsters had been killed in action, mostly at the hands of German submariners.

The first Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill was forced to defend the decision to send the boys to sea in the House of Commons. He explained to MPs: "It was felt that young officers of their age would be of great use on board His Majesty's ships, and that they would learn incomparably more of their profession in war than any educational establishment on shore could teach them."

More on World War One

Torquil, then 14, and Ronnie, 15, were assigned to HMS Goliath, a pre-dreadnought battleship that was brought out of retirement at the start of the war.

Although obsolete compared with more modern vessels, "Golly" - as she was known to her crew - could still pack a considerable punch with her four 12-inch guns.

The two boys were made midshipmen, the most junior rank for officers, who were commonly referred to as "snotties". They were to get their first taste of action not in the North Sea but in the distant waters of the Indian Ocean where HMS Goliath was sent to take part in operations against enemy warships operating out of the German East African colony in modern day Tanzania.

However, at the end of 1914 HMS Goliath had to go for a lengthy refit at the Simon's Town naval base near Cape Town in South Africa.

While there Ronnie wrote one of many letters home to his parents, telling them that he and his best friend Torquil had both enjoyed going to what he described as a few "bun worry" tea parties with local young ladies.

But in March 1915 they were ordered to head to the Aegean for the start of the fateful Dardanelles campaign. HMS Goliath's role in the operation was to help cover the landing of Allied troops on the peninsula by bombarding Ottoman positions.

Battle for Gallipoli: February 1915-January 1916

In 1915 the British decided to mount a naval expedition to bombard and take the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey; the aim was to capture Constantinople and knock Turkey out of the war

Naval attack began on 19 February, but the attack was abandoned after three battleships (including the Goliath) had been sunk and three others damaged.

Troops began to land on 25 April but by this time the Turks had had ample time to prepare, and defending armies were now six times larger than when the campaign began

Against determined opposition, Australian and New Zealand troops won a bridgehead at "Anzac Cove" but stalemate prevailed for the rest of the year

Operation was abandoned in January 1916; the Allies lost around 214,000 men, including more than 8,000 Australians and more than 2,700 New Zealanders

Resistance was fierce and the young boys would have seen the horrors of this campaign up close as they helped transfer wounded men, often nursing terrible injuries, off the beach and back to hospital ships.

In his final letter home just days before his death, Ronnie wrote: "I am as well and happy as a fiddle - there is absolutely nothing to be anxious about - just you think of afterwards."

The Ottoman high command had decided that action had to be taken to stop Royal Navy battleships from raining down destruction upon their forces.

In foggy conditions and under cover of darkness on the night of 12-13 May 1915, the Turkish torpedo boat Muavenet-i Milliye managed to sneak through the narrows and opened fire, hitting HMS Goliath with three torpedoes.

Ronnie and Torquil's old classmate 15-year-old Wolston Weld-Forester was woken up by the explosions and later described the following moments in his memoir From Dartmouth to the Dardanelles.

"Inside the ship everything which was not secured was sliding about and bringing up against the bulkheads with a series of crashes. Crockery was smashing - boats falling out of their crutches - broken funnel guys swinging against the funnel casings.

Allied troops landing at Gallipoli - HMS Goliath was supposed to cover their landing

Wolston described the ship heeling over to about 20 degrees, before holding steady for a few seconds.

"In the momentary lull the voice of one of our officers rang out steady and clear as at 'divisions' : 'Keep calm, men. Be British!'"

The ship then started to heel rapidly again. Wolston jumped overboard.

"Just before I struck the water my face hit the side of the ship. It was a horrid feeling sliding on my face down the slimy side, and a second later I splashed in with tremendous force, having dived about 30ft.

"Just as I was rising to the surface again a heavy body came down on top of me. I fought clear and rose rather breathless and bruised. I swam about 50 yards away to get clear of the suction when the ship went down. Then, turning round and treading water I watched her last moments."

There were just three-and-a-half minutes between the torpedoes striking and Goliath sinking.

Wolston was one of the lucky ones. He was in the sea for a considerable time before rescuers found him, just as he was beginning to lose consciousness through cold and exhaustion.

There were 570 others who were not so fortunate.

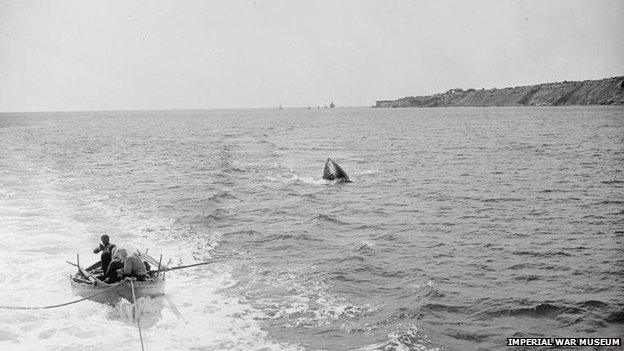

Some of the survivors from HMS Goliath

They included Torquil and Ronnie. Torquil was aged 15 and eight months while Ronnie was just a few weeks away from his 16th birthday.

Sub-lieutenant Philip van der Byl wrote this letter to Ronnie's parents: "I am sure it will be some comfort to you to hear how much we all loved your son in the Goliath, and how much we miss him. He was the life and soul of the gunroom, and always most cheerful and optimistic. His best friend was (Torquil) Macleod, who also was drowned.

"They always used to go ashore together and buy curios for you. He really was a charming boy, loved by all who knew him. On the night we were sunk he was sleeping outside my cabin, and I saw him when I turned out. He had got his safety waistcoat on, and was going quietly up the ladder on to quarter-deck. He seemed as cheerful as usual, and perfectly cool.

"When I got on to deck a few seconds later he was just going-over the port side with two other 'snotties.' That was the last I saw of him, and I shall never forget his cheery little face absolutely as full of confidence and calm assurance as it could be. He was picked up unconscious by one of the Euryaliis boats, and died on board, and was buried at sea early the same morning. Poor boy! I hoped and prayed he might have been saved, and we were all miserable when we heard he had gone... It is always the good who die young."

The Chatham Naval Memorial commemorates Royal Navy members who died at sea

Dr Jane Harrold, an archivist at the Britannia Royal Naval College in Dartmouth, has researched the stories of these youngest of British military personnel who went to war.

"They were incredibly enthusiastic. This was going to be a great adventure. It was going to be over fairly quickly as most people thought."

Perhaps the most surprising thing for a modern audience is the apparent lack of contemporary concern at teenagers being sent to war.

"There seems to have been surprisingly little opposition and a great deal of acceptance, which is surprising considering that if you had wanted to fight in the trenches you would have had to have lied about your age if you were 15 and convince the recruiter that you were 18.

"The public doesn't appear to have rallied very much against it. Not being fully commissioned officers, the parents of these 15-year-olds would still be paying fees for the training they were receiving while they were out at sea and putting their lives at risk. The only concession being that if your son died after say six months you'd get half of your fees rebated."

1919: A buoy marks the spot where the Goliath sank

But this aspect of the war remains relatively unknown even now.

"I am almost as surprised about the lack of interest now as the lack of concern 100 years ago. It seems inexplicable to me that so little is known about this. This was officially sanctioning schoolboys to go into the thick of war at a time where you weren't allowing that to happen when it came to land warfare."

The situation of the young cadets was particularly precarious as they were used to crew older Royal Navy vessels.

"There was pressure in terms of manpower. But knowing that these boys were not fully trained they weren't going to take a risk by sending them to the more modern, more expensive and more valuable ships in the fleet. Naturally they got sent to not only the oldest and least efficient but perhaps also the most exposed and most vulnerable at the same time. So it was a double whammy in terms of the risk these boys were running."

Ronnie's great nephew, Stuart Faed, is planning to travel out to Gallipoli for the 100th anniversary of the sinking of HMS Goliath.

"I feel I have to go. My grandfather always talked about his brother and I think I am doing it for him. I suspect it will be very emotive.

"I have a daughter who is 15, which is the same age as young Ronnie was when he died on board that ship. So I think that has probably brought it home to me just what a tender age he was when he lost his life for his country."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.