Five years that shaped the British military

- Published

There's currently controversy over the prospect of spending cuts for the British military. But there have been many years after World War Two in which big cuts have been made.

1946 - gearing up for peacetime

During World War Two the UK defence budget reached a peak of £86bn a year [in real terms - see note at bottom for methodology] in 1944. In the final year of the war, the defence budgets fell by 48% to about £44bn. When the war ended, Britain had to rapidly change gear for a peacetime economy. At this point the British Army numbered 3.12 million soldiers. Add in the Navy, Royal Air Force and other parts of the military and demobilisation involved five million servicemen and women.

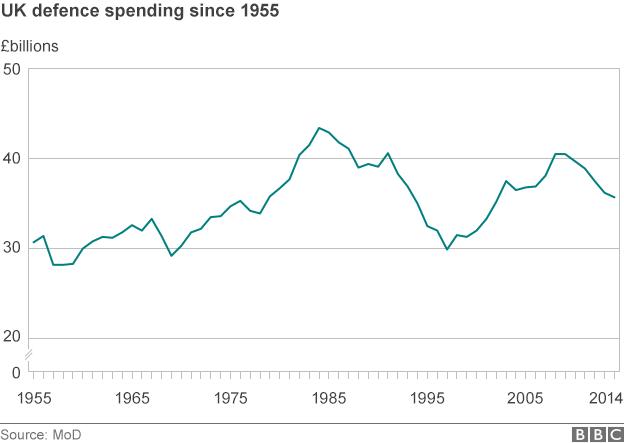

Britain had won the war but it owed huge sums to the US. At the same time, Clement Attlee's government began building the welfare state. Austerity set in and the defence budget dropped - in 1946 falling by 56% to £19.5bn. There was a steep rise in 1947 before it fell back in 1948 and 1949 with cuts of 18% and 4% respectively.

The Times in August 1947 reported "Cuts all round to meet the crisis". The petrol ration was reduced by 33%, coal miners were to work an extra half hour a day. And defence personnel would be cut to 1,007,000 by the end of March 1948, the prime minister announced. By October, further cuts were announced - the armed forces would now number 937,000 by the following April. The Conservative opposition "expressed grave anxiety at the state of the country's defences", according to the Times.

The Cold War saw British troops deployed to the border between East and West Berlin

Winston Churchill, now in opposition, made his Iron Curtain speech in 1946. There followed a slow period of realisation that the Soviet Union - formerly an ally against Hitler - was becoming a threat. It is thought the term Cold War was first used by Bernard Baruch, a White House adviser, in April 1947. The UK was moving secretly towards a nuclear deterrent. Despite demobilisation, conscription continued and in 1948 the National Service Act adopted this for peacetime. Britain's role was changing.

Attlee was dismantling the Empire - in 1947 India gained independence. British forces were still being deployed as peacekeepers to the Middle East and to police the Empire. Troops were based in Palestine in the years before the declaration of Israel's independence in 1948. The Malayan Emergency - an attempt to put down a communist uprising - began in the same year and continued until 1960.

1957 - the year after Suez

1950: Troops wait to board the Empire Windrush at Southampton to fight in the Korean war

Britain found itself at war again in the early 1950s. Winston Churchill - back as prime minister - sent almost 100,000 British troops to serve in Korea, external - 765 lives were lost. UK defence spending rose dramatically to cope with the operation. And 1952 was the year the UK first successfully tested a nuclear bomb. There was a cut of 6% in 1953, anticipating the Korean armistice of July that year. The resolution of Korea led to hopes of detente. The Times talked of an olive branch being extended from Moscow and Peking (Beijing). There were other operations for UK forces to worry about - the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya, the independence campaign in Cyprus, and Borneo, among others.

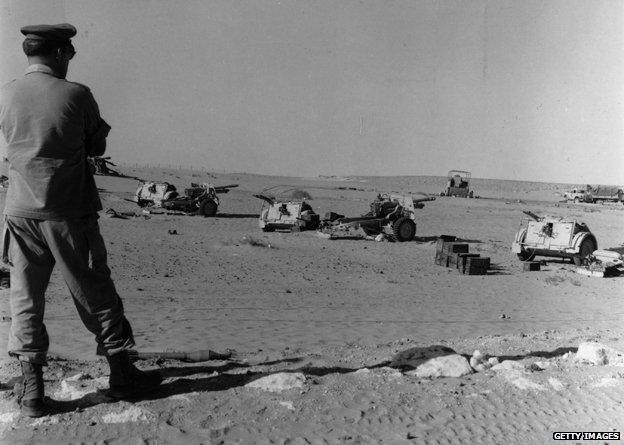

But the Suez Crisis was perhaps the definitive moment for the UK. The seizing of the Suez Canal with France, after Egypt had nationalised it, and then the humiliating withdrawal after pressure from US President Dwight Eisenhower, has been identified by some historians as the moment Britain ceased to be a great power. During the mid-1950s the UK defence budget had bobbed around - up a little in 1954, down in 1955 and up a little in 1956. But in 1957 following Suez, there was a 10% cut.

1956: A British officer looks over gun emplacements near the Suez canal

It was the first double-digit cut since the post-World War Two downsizing. Spending on defence fell below 7%. The philosophy was set out by incoming Defence Secretary Duncan Sandys in his 1957 Defence White Paper. The army was to be slimmed down again and aircraft numbers cut. The new philosophy accepted the supremacy of nuclear weapons. In February 1957 a Times report summed up Sandys' position: "We must as far as possible resist the temptation to dissipate our limited resources on forces which in themselves had no deterrent value, for to that extent we should be reducing our contribution to the prevention of war."

Sir Lawrence Freedman, professor of war studies at King's College London, says it was an attempt to reduce the cost at a time when the UK was overstretched. "The basic problem was we were still trying to manage an empire, putting a great strain on spending. Sandys' review was a shift to nuclear deterrence." Sandys also announced the end of conscription, although this didn't come into effect until 1963. The defence budget was frozen in 1958 and 1959. By 1960 the British Army was down to 315,000 men - about a tenth of its size at the end of WW2.

1969 - no place in Vietnam

The Cold War was at deep freeze during the 1960s. The early 1960s were shaped by the Cuban Missile Crisis, the end of the decade by the Vietnam War. For the first half of the decade, the UK defence budget rose in most years. But Harold Wilson's Labour government came to power in 1964 pledging cuts. It promised to do this by banishing the "pretence" of a nuclear deterrent independent from the US, while still maintaining UK bases east of Suez, and keeping the British Army on the Rhine up to size.

Defence secretary Denis Healey oversaw the scrapping of aircraft carriers but the thrust of defence policy remained the same - a reliance on the nuclear deterrent. In the second half of the 1960s, spending fell in three years - 1966, 1968 and 1969. In an interview in 1968, Healey said: "I think the services can be rightly very upset at the continuous series of defence reviews which the government has been forced by economic circumstances - and maybe economic mistakes too - to carry out."

But 1969 was a key year and showed the divergence of US and UK military spending. This was the year that US troop numbers peaked in Vietnam at 549,500. But the UK was not involved, prime minister Harold Wilson having refused to send troops. Instead, the worsening economic picture in Britain led to more cuts. Healey's 1969 defence review produced a cut of 7%, the biggest since the Sandys review of 1957. Healey committed Britain to withdrawing from its bases east of the Suez Canal by 1971. He also cancelled plans to buy US F111 strike aircraft. By the end of the decade spending on defence had fallen to 4.65% of GDP.

1977 - the effects of inflation

The UK defence budget appeared on paper to rise fast throughout the 1970s. But inflation was high - fluctuating between 10-25%. Adjusted for inflation, there were only small rises. It is often said that defence equipment costs rise faster than inflation. The reality during the 1970s was that the armed forces were being "hollowed out" by lots of small cuts, says Freedman. The Cold War had entered something of an impasse. But Northern Ireland was a drain on resources. At the height of the Troubles in 1972, there were 27,000 British military personnel based there.

At the height of the Northern Ireland troubles there were 27,000 British military personnel based there

Public finances were tight in the later 1970s. In 1976, Prime Minister James Callaghan faced a Sterling crisis and was forced to apply to the International Monetary Fund for a £2.3bn rescue. It demanded cuts and the following year Defence Secretary Fred Mulley oversaw a 3% cut in spending. His Conservative shadow, Sir Ian Gilmour, accused Labour of cutting defence spending by £100m and called on Mulley to resign.

According to the Times, in March 1977, Gilmour told the Commons the cuts were exposing the country to the danger of Soviet aggression: "The government had pretended that the defence review had cut Britain's commitments outside Nato but had not cut its Nato capability. That was untrue. They had weakened the fleet on the flank - reduced the reserves earmarked for Nato, and made dangerous reductions in the capability of the air force." By 1978, defence spending was down to 4.5% of GDP. But in this period only two Nato countries spent more on defence as a percentage of GDP - the US and Greece.

1991 - the post-Cold War world

Defence spending in the US and UK grew in the 1980s as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher took a more aggressive strategy in the Cold War. The arms race was ratcheted up, which some historians credit for the collapse of the Soviet economy.

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, and the Warsaw Pact was dismantled, the Cold War seemed over. The "peace dividend" led countries to scale down their militaries. Spending in the UK had already peaked in 1985 at 5.1% of GDP and fallen back slowly. In 1990, the Thatcher government produced Options for Change, a review looking to make the most of the "peace dividend". Alan Clark, defence procurement minister, wrote in his diaries at the time: "We are at one of those critical moments in defence policy that occur only once every fifty years." It was a reshaping of defence now that the Soviet threat had gone. And a chance to save money.

In 1992 the budget dropped 6% and the pattern continued for the next five years. Cuts were made of 4% in 1993, 5% in 1994, 7% in 1995, 2% in 1996, 7% in 1997. Spending as a proportion of GDP fell from 4.1% in 1991-92 to 2.4% by the end of the decade.

There were similar cuts from other nations. The US announced the closure of more than 100 bases and reduced its army in Germany from 300,000 to below 100,000. It was not just a response to the strategic situation. The US budget deficit was "out of control", the Times reported in June 1990, and defence cuts were inevitable. US spending fell from 6.3% of GDP in the late 1980s to 3.4% a decade later.

In the UK, the scale of the cuts met with anger from MPs from all parties. The Army was to be reduced to 116,000. The government cancelled an order for 33 Tornado jets and cut three RAF Tornado squadrons. Defence Secretary Tom King described it as "the biggest cut in real terms" the armed forces had faced for a long time.

Tornado jets take off during the 1991 Gulf war

The Gulf War created concerns that the cuts were too big. Members of the Commons Defence Committee attacked Options for Change. "The Ministry of Defence is being led by the nose by the Treasury towards reductions in Britain's armed forces which have no rational basis," Lib Dem defence spokesman Menzies Campbell said in August 1991.

King resisted calls to postpone the cuts because of the coup against Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991. King said a few days later on the BBC's World at One: "The Warsaw Pact has gone. Soviet troops have left Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and Germany is united." Protests among Tory backbenchers and the opposition went on. In an October debate in the Commons, former Conservative minister Julian Amery asked King: "Putting your hand on your heart, could you say 'yes, we could cope with another Falkland operation, with another Gulf operation?' If you can't, you had better go back to the drawing board."

Sources and working: All defence spending figures are real terms meaning that spending has been adjusted for inflation. The source is the MoD. The pre-1955 figures are only estimates. They use "current prices" spending figures, which have been turned into real terms budgets using Office for National Statistics inflation figures. Special thanks to Fenella McGerty of IHS Jane's Defence Budgets for her statistical analysis.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.