A Point of View: To the end of time

- Published

Is a point being reached where time is revealed as an illusion, asks Will Self.

"Time present and time past/ Are both perhaps present in time future/ And time future contained in time past./ If all time is eternally present/ All time is unredeemable." The opening lines of TS Eliot's Burnt Norton, the first of his Four Quartets, were written in the 1930s, but while they may be familiar to many of you, I wonder if any of us have really stopped to consider their full import. True, Eliot sounds a speculative note with that "perhaps" in the second line, yet his meaning still seems clear enough - if our perception of time as moving ever forward like a river is purely subjective, and the whole span of time - together with all actual events - has already transpired, then nothing we will ever do or say can alter the future, let alone the past. The inclination is, I think, to relate Eliot's insight directly to notions of free will, and hence to moral responsibility - the attribution of which is the thing that most preoccupies us in our social existence. However, I don't really want to discuss that but instead focus on time itself, and our conception of it.

The fourth dimension appears so much slipperier to us than the first three - so slippery, indeed, that when we attempt to fix it in our minds it slithers away from our grasp in a faintly nauseating way. Consider this - if we reject Eliot's insight and cleave to the view that the past, together with everything in it, no longer exists, while the future has yet to come into being, then all of reality must be bounded by what we think of as the present. Yet what is the present? Our own irascible versifier, Morrissey, expressed our perplexity well with his song title "How Soon is Now?" because the evanescent character of the present means it seems to be simultaneously always advancing before us, yet equally ever retreating behind. My father also expressed this strange state of affairs well when I once asked him what things had been like during his childhood in the 1920s. "It's difficult to answer," he mused, "because so far as I'm concerned it's always been… now."

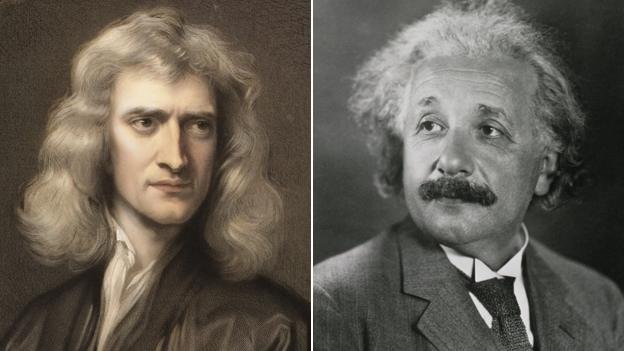

Sir Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein

I once heard some philosophers of science comparing the Newtonian and the Einsteinian revolutions in our understanding of the physical world, and one of them said that the key difference between the two was that laypeople could intuitively grasp the former's principles, whereas the mathematics describing the latter are so complex their implications can only be comprehended by the scientific illuminati. This may well be so - certainly, I lack the necessary understanding of probability theory required to be conversant with quantum mechanics, but then again, I'm also all at sea with differential calculus, the mathematics that fixes in the real world the parabolas described by Newton's laws of motion. Somehow this doesn't prevent me grasping Newton's view of both space and time as absolutes within which the phenomena we perceive can be categorised. The Newtonian universe is exactly calibrated, like a chronometer, and leaves plenty of conceptual room for a divine creator to exist outside its casing. I would argue that it's really this aspect of Newton's thinking - the murky interface between his scientific theories and his religious belief - that enables our own clarity. After all, while physical interactions may have the apparent simplicity of impacting billiard balls, it's reassuring to know there's someone who built the table.

This recourse to the notion of intelligent design will doubtless upset the atheists out there, but it's worth recalling that scientific theories aren't descriptive of any reality at all, but rather provisional rules of thumb for a universe which exhibits assumed regularities. Richard Feynman - himself an elegant explainer of relativity theory - put it thus: "I have approximate answers and possible beliefs about different things, but I'm not absolutely sure about anything." It's unsurprising, surely, that a Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist exhibits such scepticism and humility towards our enigmatic world. After all, the revolution that occurred in our possible beliefs about it between the publication of Einstein's two papers on general and special relativity means an approximate answer is… Well, is that time present and time past are both present in time future, while time future is contained in time past.

TS Eliot 1888-1965

TS Eliot, pictured in 1930

Thomas Stearns Eliot was a US-born writer, who emigrated to England aged 25 and is now considered one of the 20th Century's greatest poets

The Waste Land (1922) and Four Quartets (1945) considered Eliot's greatest works; other well-known poems include "The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock" (1912) and "The Hollow Men" (1925)

Combined radical poetic technique with an extremely conservative outlook - many later poems are informed by his conversion to Anglicanism; his alleged anti-semitism is still subject of debate

His book of light verse, Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats, was the basis for the successful stage musical, Cats

The unified nature of space/time, and the notion that this phenomenon is not some sort of limiting constraint, or measure, but a field capable of distortion by gravity, leads us back to the queasy apprehension of our own utter relativity. Try as we might, we're condemned to live our life going towards a nullity, while our past is sucked into a void. No wonder the philosophically-minded end up examining their ancestors' tombs in Somerset graveyards and writing poetry about their intimations of eternity, because even those of us who're rather more prosaic cleave to archives of personal and familial experience - our creaky photo albums and desiccated sheaves of correspondence. Indeed, what gives our human cultures any sense of cohesion at all is an almost relentless effort to shore up our collective memory of the past against the remorseless depredations of time.

"The persistence of memory", Salvador Dali (1931)

The implications of Newtonian physics took centuries to be fully expressed through technology, but it was a scant 40 years between Einstein's first revolutionary paper and the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima. The terrifying destructive power of this weaponry is a correlation, surely, of the fearsome implications of E = MC², because once we see that all time is unredeemable, such is our rage and disorientation that - like stroppy teenagers - we trash our own space. Virginia Woolf stated, in her essay Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown that "on or about December 1910 human character changed". This ringing phrase is usually quoted in contexts that suggest Woolf was registering the impact of modernity - and in particular new scientific theories and their technological applications. In fact Woolf's essay is about the difficulty she and her contemporaries have in rendering the human character through fiction. She goes on to write: "I think that Mr Eliot has written some of the loveliest single lines in modern poetry. But how intolerant he is of the old usages and politenesses of society."

Some of the old usages and politenesses of society that Eliot abjured were precisely the Newtonian conceptions of space and time, which, a decade or so after Woolf's essay was published he would meditatively subvert in Burnt Norton. But this shouldn't surprise us. Modernism as an aesthetic response leading to a cultural period is all about the unredeemable nature of time. Eliot and Pound underpinned their dissections of the present with the mythic archetypes of the past, Joyce set his vast panorama of human life within the context of a single day, Cezanne broke down the image into its constituent geometrical parts, while Stravinsky beat time until it syncopated. By doing all these things the modernists demonstrated they fully appreciated the consequences of Einstein's discoveries.

Timely thoughts

"The only reason for time is so that everything doesn't happen at once" - Albert Einstein

"But thought's the slave of life, and life time's fool; And time, that takes survey of all the world, Must have a stop" - William Shakespeare

"Clocks slay time... time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels; only when the clock stops does time come to life" - William Faulkner

"Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so" - Douglas Adams

However, we don't need to strain our necks peering up at high art in order to appreciate how Einsteinian our contemporary existence has become. Rendered collectively neurotic by the scientific proof of our own insignificance - for, if relativity is speaking, this is quite clearly the case - some of us, like Eliot, retreat back into a religious perspective, and rely on a deus ex machina to keep the time. But for the most part we concentrate our energies on enlarging the sphere of the present itself. Of course, all cultures have attempted to do this. The inscriptions carved on ancient stones are commands aimed at future generations, ordering them to stop the clock.

Stop the clocks: Picture in Hiroshima shows a timepiece, broken the moment the A-bomb dropped in 1945

But since the early 1900s our civilisation has developed more and more powerful ways of silencing the relentless ticking it knows to be a purely subjective phenomenon. What is the worldwide web, with its instantaneous access to a myriad images and sounds of our past, and its corresponding myriad imaginings of our future, if not a vast and prosthetic present? So when, exactly nine minutes and 40 seconds ago, I queried whether any of us really stopped to consider the full import of Eliot's lines, I wasn't being rhetorical. It matters not that this broadcast will be available on the BBC's iPlayer for weeks to come, because my reading of it and your listening to it now resides firmly in the past. It must do, because for us - just as much as the poet staring down at the mossy tombs of his ancestors - it's always, always… now. Isn't it?

A Point of View is broadcast on Fridays on Radio 4 at 20:50 GMT and repeated Sundays 08:50 GMT or listen on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.