The country training people to leave

- Published

The Philippines has one of the fastest growing economies in Asia - but there aren't enough jobs to go around. So every year the government teaches thousands of people the skills they need to get jobs abroad.

When I arrive at the state-run Housemaids Academy in Manila morning exercises are well under way. A squad of uniformed cleaners is poking feather dusters into all corners of the sitting room. In the kitchen trainee cooks are immersed in the finer points of salad preparation.

The academy has the feel of a soap-opera set - each room meticulously dressed to ape the reality of a grand residence. Below stairs is a classroom filled with old fashioned school desks. Here, I'm told, the trainee house servants take lessons in hygiene, respect and personal finance.

The Philippines government schools tens of thousands of maids, chauffeurs, mechanics and gardeners every year, with the express purpose of launching them into long-term service abroad.

For the state it's a win-win. These economic exiles - there are are currently some 10 million of them - send back foreign currency which is the lifeblood of the Filipino economy. And the extraordinary exodus of labour acts as a safety valve in a country struggling to provide home-grown jobs for a population rising by more than two million every year.

"We are proud of what we are doing," one of the trainee maids, Maria, tells me. "We are national heroes." That was a phrase first coined in a government propaganda campaign, and it's clear that the 20 young women now gathered around me - all immaculately uniformed and polite to a fault - desperately want it to be true.

"It can't be easy leaving your families behind," I suggest.

"We have no choice," replies Evelyn, an elfin figure no more than 5ft tall. "I have a baby at home but no way to support him. The wages I earn in Kuwait will mean my mother can raise him."

Many of the other trainees nod in sympathy - almost all, it seems, are facing the prospect of separation from their children for at least three years, possibly many more. Their reality will be prolonged servitude in an alien culture.

The mood in the academy has darkened. Half the young women before me are now weeping.

Alongside the remittances of overseas workers, there's a new phenomenon keeping the Philippines economy afloat. It's known as BPO, business process outsourcing - you could call it the rise of the call centre economy. More and more Western companies have moved their low-cost back-office operations to the Philippines.

"We've overtaken India," Dyne Tubbs, a manager at Transcom call centres, boasts as we survey her army of Filipino telephonists handling calls on behalf of a UK parcels delivery company. It's midnight in Manila, 4pm in London and the phones are red hot, as they will be until dawn.

"British companies love us because our English is not accented. The brightest graduates from our universities fight to get a job here. We only take the smartest kids. And after we've finished training them they even get your British sarcasm," says Tubbs.

One third of the Filipino population is under 15 years old. The country may have found a unique niche in the global economy but current rates of economic growth, though impressive, will not sustain a population projected to double from 100 to 200 million within 30 years. Which is why Jane Judilla may just hold the key to the Philippines economic future. Jane isn't an entrepreneur or a politician, she's a reproductive health worker who spends her days in some of Manila's most squalid slums.

Thanks to a law pushed through by the government last year, she's now permitted to offer the poorest Filipinos free access to condoms, the contraceptive pill, even sterilisation for women who want it. The Catholic Church, which commands the loyalty of 90% of Filipinos, fought the initiative tooth and nail but the clerics lost.

Judilla introduces me to Sheralyn Gonzales, a whey-faced woman of 30 with 10 children and another on the way. I ask Gonzales whether she's happy. "I'll be happy when I've had the baby and can get sterilised," she says. "My eldest has dropped out of school, and we can barely afford to educate the others. I tell my children to have two kids, then use contraception."

If the next generation of Gonzales's heed her advice their country's future is promising. If not, tens of millions of young Filipinos may find themselves stuck in a poverty trap, still dependent on overseas labour as a means of escape.

You can watch HARDtalkon the road in the Philippines on Tuesday 10 March on BBC World News at 04:30, 09:30, 16:30 and 21:30 GMT. It's also on the BBC News Channel at 00:30 and 04:30 GMT. You can catch up later on the BBC iPlayer.

From Our Own Correspondent, externalis on BBC Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 and Thursdays at 11:02 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast

For more on the BBC's A Richer World, go to www.bbc.com/richerworld - or join the discussion on Twitter using the hashtag #BBCRicherWorld, external

More from the Magazine

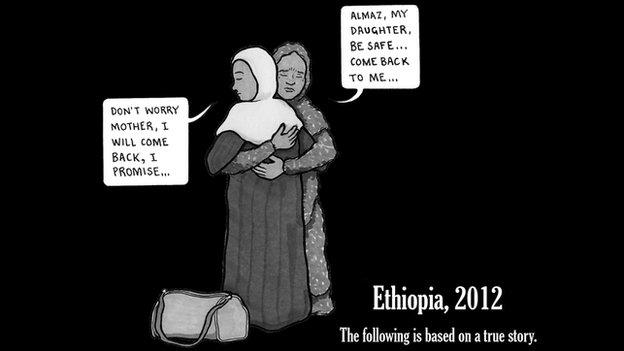

Benjamin Dix and Lindsay Pollock tell the disturbing story of a young Ethiopian woman abused by her employers in Saudi Arabia.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.