The officer who refused to lie about being black

- Published

Today it's taken for granted that people of all ethnic groups should be treated equally in the armed forces and elsewhere. But as Leslie Gordon Goffe writes, during World War One black officers in the British armed forces faced a system with prejudice at its core.

When war was declared in 1914, a Jamaican, David Louis Clemetson, was among the first to volunteer.

A 20-year-old law student at Cambridge University when war broke out, Clemetson was eager to show that he and others from British colonies like Jamaica - where the conflict in Europe had been dismissed by some as a "white man's war" - were willing to fight and die for King and Country.

He did die. Just 52 days before the war ended, he was killed in action on the Western Front.

Clemetson's first taste of combat was in 1916 on the Macedonian Front, in Salonika.

"It is as much like hell as anything you can think of," wrote a soldier who served alongside the Jamaican.

On the frontline for eight months, under constant bombardment by big guns and badly traumatised by "shell-shock", or what's now known as post-traumatic stress disorder, Clemetson, a 2nd lieutenant, was evacuated to a military hospital in Malta.

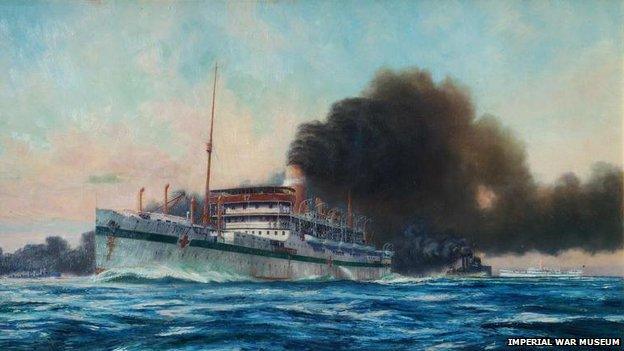

Oscar Parkes' painting of the sinking of the Dover Castle

Declared physically fit, but in need of psychiatric care, Clemetson was sent to Britain aboard the hospital ship Dover Castle, which, after a day at sea, was torpedoed by a German submarine and sank off North Africa on 26 May 1917. "Dastardly," a British newspaper roared. "The enemy must be punished!"

Rescued, the young Jamaican, who'd been diagnosed with "neurotic depression" and "stress of service" from his terrible time at the front, was taken in June 1917 to the Craiglockhart psychiatric hospital for officers in Scotland.

There, Clemetson was cared for, his medical records show, by Dr William Rivers. This pioneering physician developed a "talking cure" which helped heal soldiers who, frozen with fear from combat, were depressed, unable to sleep and eat properly, and were distraught at being branded cowards by many.

Also being treated at the hospital was the war poet Wilfred Owen, a 2nd lieutenant who had written about the futility of war and the waste of young life. Owen, like Clemetson, had been suffering from shell-shock. "These are men whose minds the Dead have ravished," reads Owen's poem Mental Cases.

Clemetson spent two months at Craiglockhart, and was almost certainly the only black officer treated there. While there, his name was mentioned briefly in the hospital magazine, The Hydra, edited by Wilfred Owen.

Two years before, in 1915, he became one of the first black British officers of WW1. But the 1914 Manual of Military Law effectively barred what it called "any negro or person of colour" from holding rank above sergeant, according to Richard Smith, author of Jamaican Volunteers in the First World War.

Nevertheless, Clemetson became a 2nd lieutenant in the Pembroke Yeomanry on 27 October 1915.

History has long recorded another black soldier, British-born Walter Tull, as the first to become an officer. But by the time Tull became a 2nd lieutenant in the Middlesex Regiment on 30 May 1917, Clemetson had been an officer for going on two years. There is a distinction - Clemetson was in the Yeomanry, part of what was then the Territorial Force, rather than the regular Army.

Walter Tull died at the Battle of the Somme, March 1918

Another candidate for the first black officer is Jamaican-born George Bemand. But he had to lie about his black ancestry in order to become an officer. Bemand, whose story was unearthed by historian Simon Jervis, became a 2nd lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery on 23 May 1915, four months before Clemetson became an officer and two years before Walter Tull.

When the teenage Bemand and his family migrated to Britain from Jamaica in 1907, and the ship he was on made a brief stopover in New York, Bemand, the child of a white English father and a black Jamaican mother, was categorised by US immigration officials as "African-Black". Yet, asked in a military interview seven years later, in 1914, whether he was "of pure European descent", Bemand said yes. His answer was accepted.

George Bemand lied about his black ancestry to ensure his commission

But Clemetson took a different approach.

"Are you of pure European descent?" he was asked, in an interrogation intended to unmask officer candidates whose ethnicity was not obvious and who were perhaps light-skinned enough to pass for white. "No," answered Clemetson, whose grandfather Robert had been a slave in Jamaica, he was not "of pure European descent".

By telling the truth about his ancestry, Clemetson threatened to disrupt the military's peculiar "Don't ask, don't tell" racial practices, which were conducted with a wink and a nod.

The recruiting officers would probably have preferred that Clemetson claim he was white and leave it at that. If others had followed Clemetson's stance, the military establishment could no longer claim, if pressed, that it barred men who were "negroes or people of colour" from becoming officers and that it kept leadership roles in the military for men "of pure European descent".

The question of race seemed to shape Clemetson's brief military career. Military officials spent a lot of time trying to categorise him.

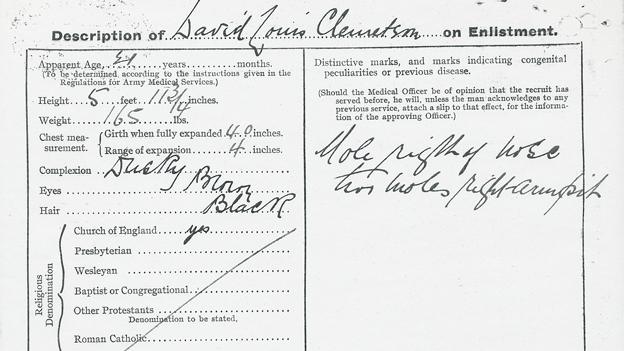

In 1914, shortly after the war began, and Clemetson had enlisted, the Jamaican was examined by a military doctor. Asked to describe what "complexion" Clemetson was, the physician didn't write black or white in his medical report. Instead he decided that Clemetson was "dusky", or between light and dark.

Clemetson's enlistment form - for the category "Complexion" a doctor has written "dusky"

The military did not know what to make of their new recruit, who they saw only in terms of the shade of his skin. But there was much more to the young Jamaican than this.

Clemetson had been born into a wealthy Jamaican family which had a complicated history. Clemetson's grandfather Robert, a one-time member of parliament in Jamaica, had been a slave. Robert's owner, who was also his father, freed him and went on to leave him money, a sugar plantation, and even slaves, in his will.

This dubious inheritance allowed the Clemetsons to emerge at emancipation rich and powerful, and part of a light-skinned black elite in Jamaica which dominated the British colony. Large landowners in St Mary's parish on the north coast of Jamaica, Clemetson's family also became rich in the banana trade after setting up, in partnership with an Italian-American family in Baltimore, a company to ship and distribute Jamaican bananas and other fruit in the US.

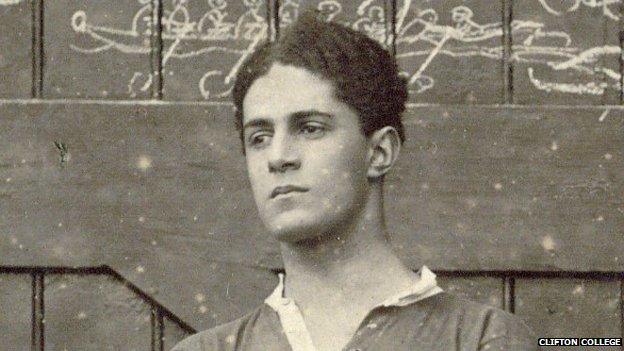

The money from these enterprises kept the Clemetsons in comfort in Jamaica and paid for their children to attend a variety of public schools and universities in Britain. David Clemetson attended Clifton College in Bristol and later Trinity College, Cambridge. One of the wealthiest young men in Jamaica, had Clemetson not gone off to fight, he would have returned home after university and settled down to life as a rural Jamaican landowner.

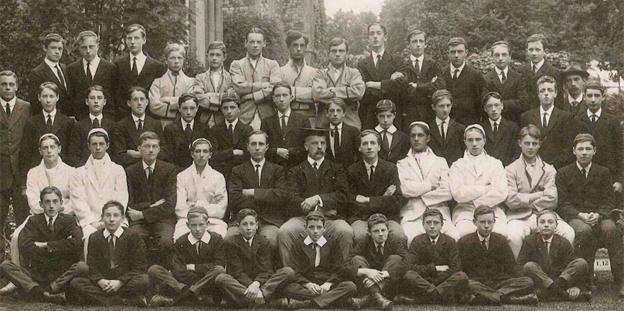

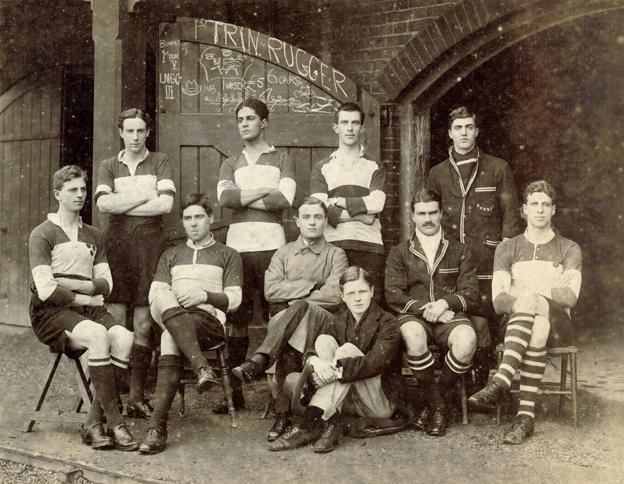

Clemetson pictured at Clifton College (front row seated, fourth from right)

Instead, he responded to Britain's massive war recruitment drive.

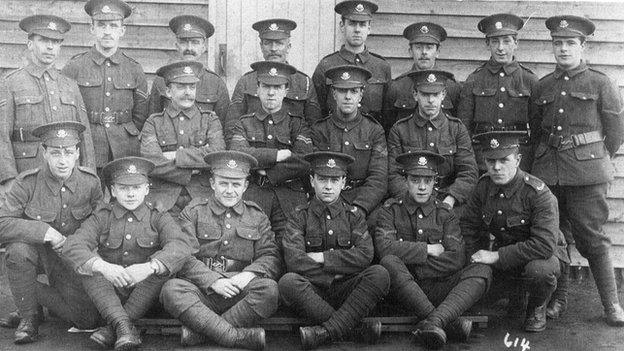

Acknowledging the need for black and Asian men from its colonies, Britain enlisted the help of West Indians, Africans and Indians, who they confined mostly to segregated units and ordered to do some of the most dangerous and dirty jobs, among them digging and emptying toilets, burying the dead, and transporting live shells.

It's estimated a million Indians, 100,000 Africans, and 16,000 West Indians served in the rank and file, in segregated units like the British West India regiments. In Jamaica, Clemetson's cousin Cecil did all he could to encourage young men on the island to volunteer.

Troops of the West Indies Regiment cleaning their rifles on the Albert to Amiens road, September 1916.

"All able-bodied men should go forward and show their patriotism," roared Cecil at a recruiting rally in St Mary's parish, Jamaica, in 1915. "No country's subjects were better treated," he claimed, "than those of the British Empire."

The British military hierarchy decided it could do no harm to turn a blind eye to its own racially discriminatory laws and allow a handful of black soldiers - among them Tull, Bemand, and Clemetson - to become officers, in charge of white troops.

But it was a fairly well-kept secret. Had they been aware, many Britons would have opposed even a small, select group being allowed to bypass the rules and give orders to whites. "The presence of the semi-civilized coloured troops in Europe was, from the German point of view, we knew, one of the chief Allied atrocities. We sympathized," Robert Graves wrote in Goodbye To All That.

But others thought this foolishness, faced as Britain was with possible defeat to Germany. Maj Gen Sir AE Turner said it would have been "the height of stupidity" not to allow "coloured subjects of the Empire… to take part in the war, and take their part… in crushing the Hun".

The black officers who did make it were remarkable men.

Walter Tull was a celebrated professional footballer. Another distinction might have been glowing recommendations from powerful military officials.

Class was a factor as well as race: Clemetson (back row, 2nd from left) rowed for Trinity College, Cambridge

Education and class were a massive factor too. George Bemand came from a well-off family and attended a prestigious public school, Dulwich College. He had also been a member of the Officer Training Corps at University College, London, and been recommended by a Brigadier-General, AJ Abdy. The general scribbled earnestly on Bemand's application: "I am willing to take him."

Clemetson, of course, was wealthy and came from a planter family in Jamaica, attended a respected public school where he was a member of the Officer Training Corps, went on to Cambridge where he was in the rowing team, and also had recommendations from important military people.

Clemetson in Clifton College's Officer Training Corps (front row seated, centre)

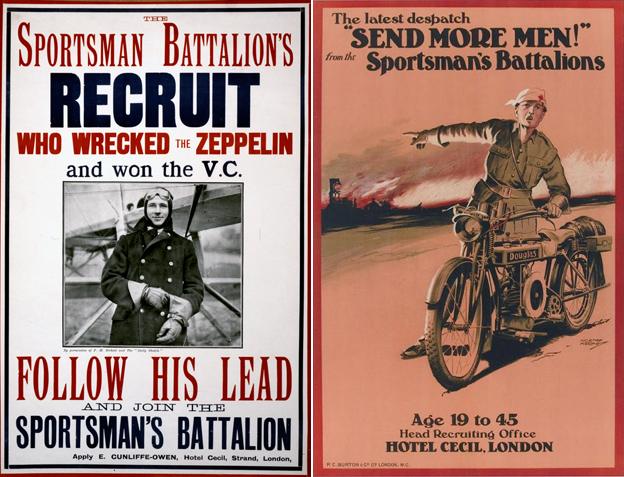

He received a recommendation from Lt Col HJH Inglis of the Sportsman's Battalion of The Royal Fusiliers, the regiment Clemetson had belonged to in 1914 before he transferred in 1915 to the Pembroke Yeomanry to become an officer.

He had been attracted to the glamorous Sportsman's Battalion because it had advertised itself as a special unit for men who were at least 6ft tall and athletic, like Clemetson, who had played rugby and cricket at school before rowing at university.

Apart from the recommendation from Inglis, Clemetson also received encouragement in becoming an officer from FC Meyrick, a lieutenant-colonel in the Pembroke Yeomanry. Meyrick met and interviewed Clemetson. The Jamaican was, he reported, "in every way eligible and suitable for a Commission".

But besides the recommendations, the athletic prowess, and public school backgrounds, what it appears the military establishment most wanted black officer candidates to have, was light skin - preferably light enough to "pass" as white and fool all but the most observant.

Those who wanted to become officers but were darker-skinned, would often find themselves rejected, even if a powerful person, like the governor of Jamaica, intervened on their behalf. Take, for example, the case of Jamaican government official GO Rushdie-Gray, mentioned in Richard Smith's book.

Despite an agreement between Jamaica's governor and the War Office to make Rushdie-Gray an officer, when the Jamaican arrived in London in 1916 he was refused a commission because he was judged too dark-skinned.

"Mr Gray called today, he is presentable, but black," a War Office memo reads. "I am surprised at the Governor recommending a black man without previously informing us of his colour." There is, crucially, the memo says, "no absolute bar against coloured men for commissions… but that they did not expect Mr Gray to be the colour he is."

It appears, too, that George Bemand's younger brother Harold was blocked from becoming an officer for similar reasons. Both attended public school but while George, who was noticeably lighter than his younger brother, became a 2nd lieutenant, Harold became only a gunner - equivalent to a private. It was clear the military had decided if it was going to have black officers, they would be as light-skinned as possible.

On 26 December 1916, a year and a half after he became an officer, George Bemand, aged just 24, was killed by an enemy shell in France. On 25 March 1918, a year after he became an officer, Walter Tull, aged 29, was also killed in action on the Western Front in the "Spring Offensive". Tull's body was never recovered.

As for David Clemetson, after serving on the Macedonian Front in 1916 and being torpedoed and rescued on his way to Britain in 1917, he ended up at Craiglockhart. The hospital seems to have had a contradictory role.

Its job was to both treat the afflicted officers, but also to patch them up quickly and get them back to the front line.

Clemetson's medical records show in the two months he spent at Craiglockhart, doctors there couldn't seem to decide whether he was getting better, or was in need of more care.

Craiglockhart hospital in Edinburgh - now part of Napier University

On the one hand, a report reads, he was in need of "further treatment". But on the other hand, the report reads a few lines later, Clemetson had, it said, "improved much". Other reports show he was not sleeping much, and when he did he had terrible nightmares. His legs had also become so weak he could not stand properly and, the medical reports acknowledges, "his memory is not what it should be".

Clemetson did have some good news while at Craiglockhart. To his surprise, in July 1917, a letter arrived from the War Office informing Clemetson he had been promoted to full lieutenant, the only black person, it appears, to hold this rank in the British armed forces during the war.

More from the Magazine

A century ago the British Army set up Bantam battalions for men under 5ft 3in. Why were short men put in special units during World War One?

But it was a garland strewn with thorns. He had received his promotion merely because the length of his service entitled him to it as a matter of course, not because of bravery in the face of the enemy.

After two months in Scotland, in August 1917, Clemetson was declared fit for duty and given three weeks' leave, which he used to go to London, where he stayed in rooms at the West Indian Club, off Whitehall, and also visited cousins.

His leave over, he reported to the 24th Welsh Regiment headquarters in Wales. Just before his regiment departed for the front, a transfer request came from the commander of a regiment in England who wanted Clemetson to be allowed to remain behind in a reserve unit.

The request was denied by his commanding officer. "This officer is serving with the Welsh Regiment and cannot be spared."

Clemetson was returned to the fighting in March 1918 and was dead six months later, killed in action in the Somme region on 21 September 1918, just 52 days before the war finally ended. He was 25.

A year after his death, the two pounds, 17 shillings and sixpence Clemetson had in his pocket when his body was recovered, plus £169 in pay he was entitled to, was sent to his mother Mary in Jamaica.

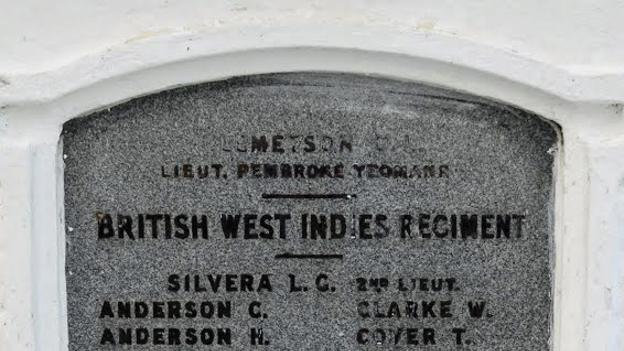

Buried in the Unicorn Cemetery in northern France, Clemetson's name also appears on the war memorial in his Jamaican hometown of Port Maria, St Mary.

Unicorn war cemetery in Vendhuile, northern France, where Clemetson is buried

A portrait of Clemetson was displayed, for a time, in a special war collection at the Institute of Jamaica in Kingston but was damaged in a hurricane and has since gone missing.

This poem, In Memoriam, written by a friend, was published in the Jamaican Gleaner newspaper in 1918, a few days after Clemetson's death: "Somewhere in France you are sleeping/The warriors last sleep/Far from the land that gave you birth/And the eyes that for you weep./…So a last salute we'll offer you,/And a last farewell we'll wave;/God rest our gallant countrymen/Till we meet beyond the grave."

War memorial in Port Maria, Jamaica: Clemetson's name can be made out at the top

Lauded for a time in Jamaica, in Britain David Clemetson is not known, at all. At Trinity College, Cambridge, he has not been recognised. Clemetson was left off the war memorial in Trinity College Chapel, which features 618 Trinity students killed fighting in the Great War.

This though was an accidental omission. Clemetson had only completed two of the three years of his degree before joining up. Had he alerted the university, special provisions would have likely allowed him to graduate.

Having been notified of their alumnus's role, Trinity College may now right their omission. "I feel he should be recognised," says college archivist Jonathan Smith, who found a photograph of Clemetson in an old file recently. "Surely he should be remembered."

The chapel at Trinity College, Cambridge: Clemetson is not among 618 students mentioned in its war memorial

So, who really should be remembered as the first black British officer? Should it be George Bemand, who felt forced to claim to be of pure European ancestry? Should it be Walter Tull? Several television films have been made about Tull and books written about him. In August 2014, The Royal Mint recognised Tull by making him the subject of a £5 coin to commemorate the centenary of the war.

To recognise David Clemetson as the first seems strangely ironic. Clemetson, like Bemand, lived a privileged life that set him apart from the great majority of black and Caribbean people of their era.

Yet, now their stories have been unearthed, they will join Tull in being recognised as pioneers, who helped break the British military's colour bar during WW1.

Correction: In this piece, a paragraph about the manual of military law has been changed to add attribution.

Find out more

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.