One-man rule in Israel's hippy micro-state

- Published

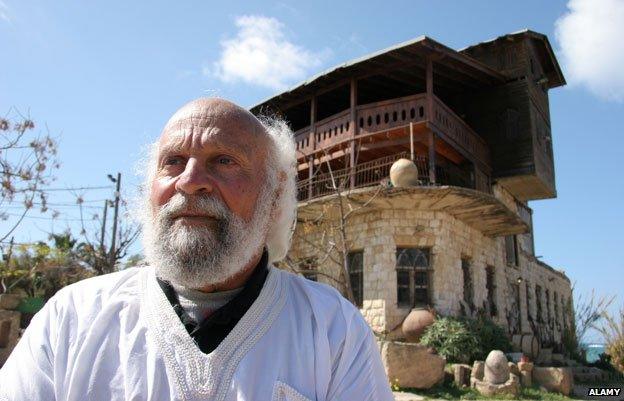

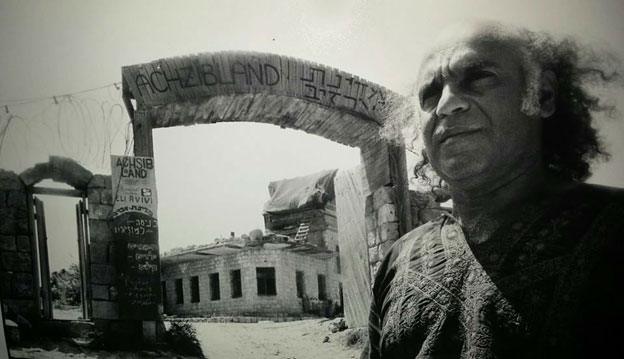

President Eli Avivi, photographed in Achzivland in 2006

While most Israelis vote for a new parliament next week there's one place in the north of Israel that will be an election-free zone - one-man rule has been the way there for more than 40 years.

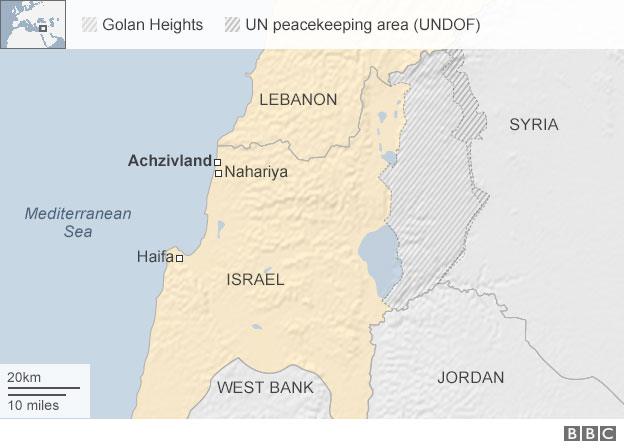

On Israel's coastal road, just south of Lebanon, lies a crossing into a land of another kind.

Large blue iron gates with white painted signs mark the border, but there is no entry procedure - visitors just arrive, then go and look for the president.

This is Achzivland, perhaps the most unusual piece of territory in the Middle East. It has the trappings of a state - a flag (of a mermaid), a national "anthem" (the sound of the sea) and a constitution declaring the president democratically elected by his own vote (never actually cast).

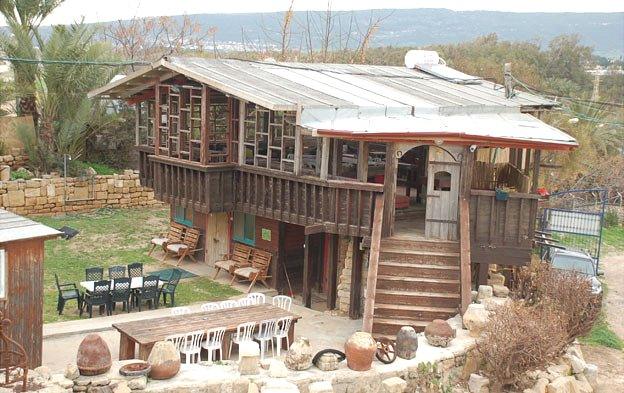

Achzivland also has a House of Parliament - a timber structure with scatter-cushions round a table - though it has no serving MPs and has never held any sessions.

It also issues - and stamps - its own passport, which requests bearers be allowed "to pass freely without let or hindrance" wherever they may travel.

Set among picturesque landscape, and with a history stretching back to the Phoenicians, Achzivland has been governed by its oldest inhabitant, Eli Avivi, and his devoted First Lady, Rina, since the couple "seceded" from Israel in 1971.

Next to the ailing Sultan of Oman, "President Avivi" is the longest-serving ruler in the region, having survived several attempts by one of the most powerful nations in the Middle East to oust him - not surprisingly, Israel has never recognised Achzivland.

But the tiny "state" has stood its ground, with a gutsiness well beyond its size.

Eli Avivi: "They do everything they can to take me away from here."

Now 85, Eli is frail, hard-of-hearing and slow, but with wispy white hair, trademark kaftan and a shepherd's staff he cuts a figure befitting his legendary reputation.

Resting outside his "palace" - a small wooden cabin, fanned by the cool sea breeze - Eli looks out across the land where he has lived, and fought, since the early 1950s.

"I am the president of a very small country," he says, his voice raspy and weak, "but I have a lot of problems with the Israeli government. They didn't want me to live here and did everything they could to take me away from here. It was like a kind of war between the government and me!"

Born in Persia, he arrived aged two in what was then British Mandate Palestine, brought by his father on a voyage which began his life-long love of the sea.

As a youngster he was caught and let go numerous times as he carried out acts of sabotage against British troops. Then at the age of 15 he joined the Palyam - the "underground" Jewish navy - and helped smuggle Jewish refugees into the country, before fighting the British, then Arab forces during Israel's 1948-49 War of Independence.

After the establishment of the Israeli state, he returned to sea as a fisherman, working on boats from Africa to Scandinavia, including spending a year "as an Israeli living with Eskimos" in Greenland.

But then, in 1952, on a trip to visit his sister, Eli came across Achziv.

Profile: Achzivland

Head of state: Eli Avivi (president-for-life)

Political system: "The president is democratically elected by his own vote"

Size: 3.5 acres

Population: Two

Borders (self-declared): North - Kziv stream; South - Bukbuk hill; East - Antioch Road; West - Mediterranean Sea

Economy: Tourism; entrance fee to National Museum

Flag: Mermaid on background of old Achziv building

Anthem: Sound of the sea

Foreign relations: "Friendly with all the countries in the world, with a special favour for Israel"

Foreign recognition: None

Defence forces: "Fans from all over the world and true friends"

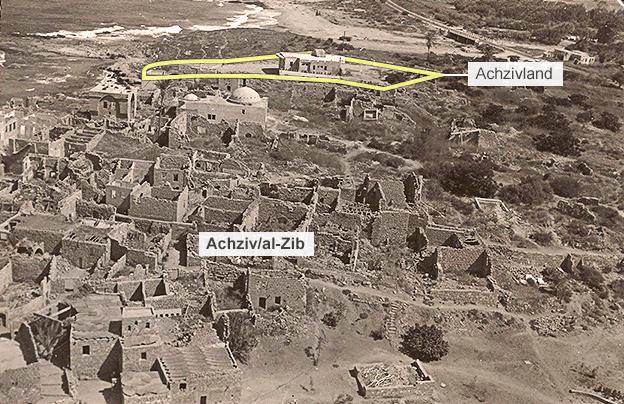

A former Arab fishing village known in Arabic as al-Zib, its residents fled, resettling in nearby Acre or Lebanon, when it was conquered by the Jewish army in 1948.

Eli found the abandoned village derelict - and, after his years of wandering, decided to stay. He caught fish, which he sold to the local kibbutz, and built himself a house.

Achziv was an oasis of tranquillity and started to attract young people who would come and hang out with Eli. As well as fishing and hunting for antiquities, Eli took up photography (developing a penchant for girls posing semi-naked or nude) - a pastime which would see him amass more than a million photos, which are now stored in a warehouse in Achzivland.

It was an idyllic existence. But before long the Israeli army said it wanted the land for a military base, and Eli's troubles with the authorities began.

He had a lease on just two buildings so he wrote to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, who replied expressing his support, much to the military's chagrin.

According to Rina, the army agreed to let him stay on condition he worked as an undercover agent for the Shin Bet, Israel's domestic intelligence agency - which, she says, he did.

Eli had won the first round, but bigger battles lay ahead.

To make ends meet, Eli started to let out lodgings and with its free-and-easy ethos Achziv became a haven for hippies - an Israeli Haight-Ashbury - where young people would roam, shed their clothes, play music, smoke drugs and party.

"People came to see the sea, to take in the sun without bathing suits, most of them smoking grass - it was a place where you came to feel free, this was the idea," says Shlomo Abramovitch, a former investigative journalist in the area.

Rina Avivi, First Lady of Achziv, on the area's ancient and recent history

"Eli Avivi was a kind of unique personality. He was very friendly and a bit of a legend among Israelis."

Achziv was also a magnet for celebrities, among them Hollywood A-listers. Paul Newman hung out there while filming Exodus in 1960, and Sophia Loren was a frequent visitor.

"When she saw the place she absolutely loved it," recalls Rina. "I was a teenager and she was one of my idols - and she taught me how to cook spaghetti here!"

Actress Sophia Loren in Achzivland in 1966

Meanwhile, as the Israeli state established itself and building programmes expanded, the government declared its intention to turn Achziv into a national park. One day in 1963 it sent in bulldozers to demolish the remains of the old village - including the land around Eli's home - intending to replace it with turf.

To Eli, this was a wanton act of historical and environmental vandalism.

As an enraged Eli Avivi stood on a wall to take photographs of the destruction, a bulldozer knocked it down, leaving him nursing several broken bones, he says.

The final straw came in the summer of 1971 when officials erected a fence around Eli's diminished land, cutting off his access to the beach.

In a defining moment in the birth of their nation, Eli and Rina ripped up their Israeli passports and declared Achziv independent - only to be arrested and taken to court.

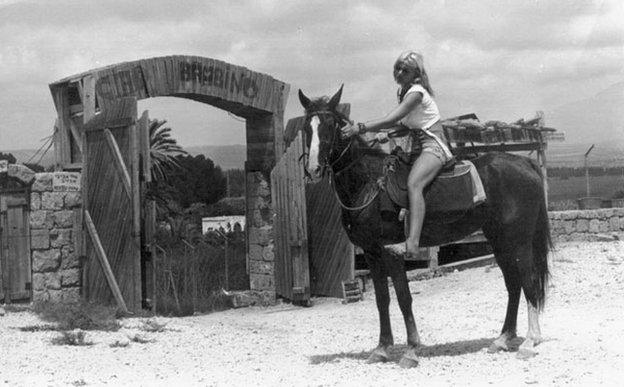

Rina in the 1960s

According to Rina, the judge threw out a charge of "creating a country without permission" but fined the couple one lira for destroying their passports, and ordered their release.

The case of the breakaway hippy state started to attract the attention of the media, and this presented Eli with an opportunity. In his new capacity as president, he called a press conference and led dozens of peaceniks in a sit-in.

"This national park may be fitting for Tel Aviv but not Tel Achziv," President Avivi told TV crews. The regional council had issued a demolition order to destroy the parliament building, he said - then he promptly appointed all the protesters Achziv MPs, and instructed them to go and start a campaign.

"We did it for publicity, because the government was stronger than us," recalls Rina. "The media started to write a lot about it, and people started to believe it, and so long as they did there was more chance the government would leave us alone."

In fact this wasn't the first time Eli and Rina had made the headlines - only months earlier they had been at the centre of a cross-border kidnap attempt.

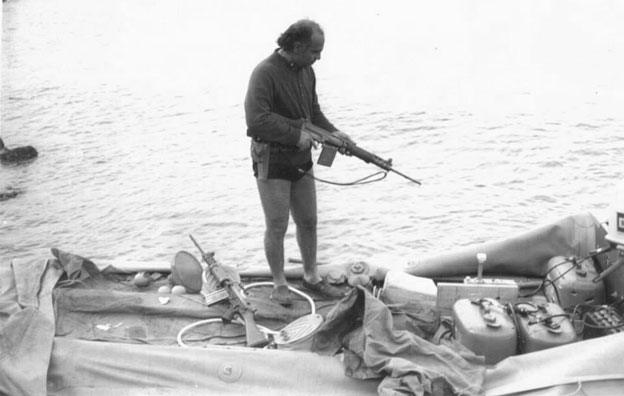

On the night of 1 January 1971 six Palestinian gunmen came by boat from Lebanon just three miles (5km) away, and landed on the beach at Achziv. According to Rina, the crew fooled the coastguard into letting them past, saying they were fishermen going to see Eli Avivi. One of the gunmen entered the house but Rina stopped him at gunpoint, and he dropped his weapon and a bag containing grenades.

"He was expecting to find Eli and got a shock when he saw a beautiful, blonde woman with a gun instead," she says.

Within minutes the army arrived and sealed off all the roads for miles around. Two more gunmen were caught at the boat, while the other three were captured inland.

"People saw a thousand troops heading here, but because the army imposed a media blackout they did not know why and rumour started to spread that Israel had gone to war with Achzivland!" laughs Rina.

The infiltrators, who belonged to Fatah, had planned to kidnap Eli, she says, and take him to Lebanon.

When the blackout was lifted, one tabloid newspaper reported the incident under the headline: "Terrorists wanted to kidnap Israel's number one nude photographer!"

The incident enhanced Eli Avivi's reputation and added to a life story where fact and fiction were fast becoming difficult to separate.

Israelis flocked from far and wide to experience Achzivland, much to the annoyance of the authorities, who were fed-up with its defiant hippy king.

In a sign of the breakaway country's popularity, when Achzivland decided in 1972 to put on a rock festival - "like Woodstock", says Rina - there were traffic jams for 60 miles (94km) around.

"All of Israel came to this festival. We lost control. Everyone burst in, like a herd," recalled Meir Kotler, the festival's producer, in the 2009 documentary Achziv, a Place for Love.

In the meantime, Eli Avivi continued to build his state, getting guests to help with chores. Achzivland was "the only country in the world which puts its hippy residents to productive and useful work," he has been quoted as saying.

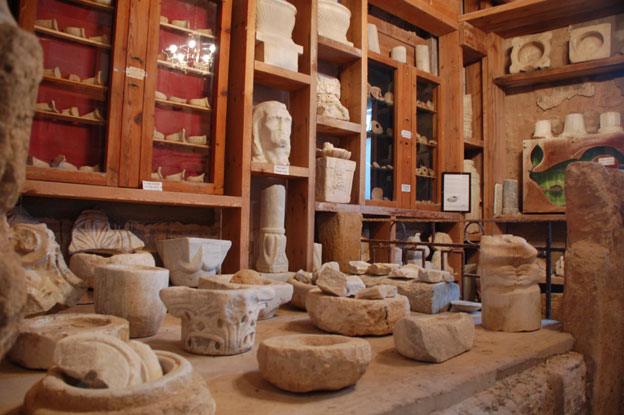

Eli also established an impressive "national museum" in the former house of the Arab village chief, displaying thousands of artefacts he had found on dives and digs - from ossuaries [a container for human bones] to pieces of jewellery to rusting nautical instruments.

By law, many of the items belong to the Israel Antiquities Authority, which considers them on loan even though it does not officially recognise the museum. "The archaeological office is the only office of government we don't have a problem with," says Rina.

During the years that followed, a protracted legal battle took place between Eli, the regional council, the Land Administration and the Nature and Parks Authority, but the authorities gradually got their way.

Most of Achziv became absorbed into the national park and Eli was prohibited from holding festivals in Achzivland.

He insists though that he has been misunderstood and that he was never anti-Israel.

"I love Israel the place, but not the government, because they never understood why I came here," he says.

"They didn't like me making a little country. They think it's something done against Israel, but this is not true."

In fact, according to one report, in a demonstration of patriotism in 1978, when Israel launched a major offensive against Palestinian militants in southern Lebanon, President Avivi announced he had "opened my airspace for Israeli planes to overfly Achzivland on their way to Fatahland".

These days, he says, the authorities mainly leave him alone. "I'm stronger now than before. There's nothing they can do or say to me," he says.

After years of confrontation, the two sides have reached an accommodation. Achzivland pays the government for access to the beach through the fence, while on the main road outside, an official tourist sign points the way to "Eli Avivi" (not "Achzivland", which might perhaps be taken as signalling recognition).

As for the future, Eli says he has no plans to appoint a successor. "After I'm gone, my wife will decide what she wants," he says.

What Rina wants is to preserve Achzivland as a permanent memorial to Eli Avivi, whom she describes as "the best president ever", and has opened talks with the Israeli government in the hope of achieving this goal.

"Achzivland is not for sale. The life here is not for sale," she says. "Everybody who comes here feels like it is paradise, and you cannot put a price on that."

Video and contemporary photographs by Alon Farago. Archive photographs courtesy of Eli and Rina Avivi.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.