The Democratic Republic of Style

- Published

When you got dressed this morning, how much thought did you put into your clothes? Probably not as much as a group of young men in Kinshasa who, despite living on one of the world's poorest countries, are obsessed with designer labels and fashion.

Six Lokoto comes striding across the square in front of Kinshasa's central train station, holding the hand of his minister. A more unlikely pair you could not imagine - Six, a modern-day hipster dandy, dressed in a top hat, smartly tailored black coat, red hoodie, silver pendant hanging around his neck, and, well, his minister.

"I have always known I was a Sapeur," Six says. "You feel it from the day you are born."

A Sapeur - a member of La Sape - the Society of Ambience-Makers and Elegant People.

Six is the Sapeur captain. He's just back from the catwalks of Paris, and as we sip cold bottles of Primus beer in the midday heat he explains the Sape way of life. Learning the style and attitudes of an elegant person, he says, is like studying for a doctorate in philosophy at the Sorbonne.

"It is a spiritual experience," he says. "It is like a religion." I look at his minister, who's beaming - he obviously doesn't consider this blasphemous in the slightest. As I found out, nearly everyone in Kinshasa loves the Sapeurs.

The economy in the Democratic Republic of Congo is growing at a rapid clip. People are getting wealthier. And when people have more money they spend it on more and better food, mobile phone credit, beer, going out to nightclubs and, of course, on clothes.

The next day I visit Six at his home - a small room in the dusty district of Matonge, filled with tin-roofed shacks, crumbling shops and dirt roads. It's 30 minutes and a world away from the gleaming new buildings in Kinshasa's Centre-ville. So wouldn't it be an idea to spend a bit less on clothes and a bit more on slightly more salubrious digs?

"Nothing," says Six, "is more important than fashion."

In his small room he yanks a suitcase out from under the bed, unzips it and pours out a stream of dozens of pairs of shoes, carefully picking the ones he'd like to show off.

The same with shirts, jackets, coats - he finally settles on khaki overalls, a leather jacket, jeans studded with pins and jewellery and some designer wellington boots - a combination that really shouldn't work at all but at the same time is absolutely perfect.

Some other Sapeurs last year got to star in a popular ad campaign for a famous beer brand. Those mostly older men were from Brazzaville, the capital city of the Republic of Congo just across the river. Between the two groups of Sapeurs there is the intense rivalry of neighbours. They even hold regular competitions, a combination fashion show and dance-off.

Of the Brazzaville Sapeurs, Six is scathing: "They are about cheap clothes," he says. "We are expensive. They are like secretaries - we are the bosses."

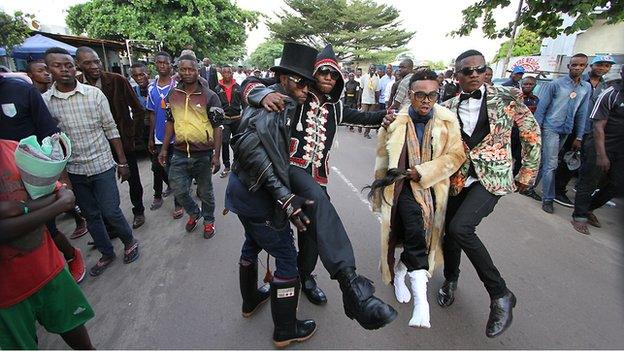

Kinshasa's Sapeurs are younger, their style more cutting edge, with influences from high fashion to hip-hop. Once Six is dressed to the nines we travel to a nearby square - his mates show up dressed in tuxedos with fluorescent patterned jackets, fur coats, and costumes that would not look out of place on a guard at the Tower of London.

They strut and bounce, dance and flounce. Everyone stops to stare, and when they are ready to have serious fun they lead an impromptu parade through the streets of Matonge.

Rush-hour traffic comes to a halt. People come out of their houses and jump up from their chairs at roadside cafes. Football games are abandoned. Kids start to whistle and shout. Within minutes we are in the middle of a crowd of hundreds. Young men sing: "We love the Sapeurs." It is chaos - unbridled pride and joy.

Now of course, I should point out that this is a country where civil war still rages a thousand miles to the east - where the democratic transition is quite arguably neither democratic nor a transition. Six weeks ago anger at President Kabila turned in to riots in which nearly 50 people were killed. The Sapeurs weren't strutting then - nobody was.

There are terrible problems here with HIV, illegal mining, and of course all that stuff that kills poor people just because they're poor: malaria, stomach bugs, car accidents, childbirth.

That's reality of course. But so is this. Night has fallen in Kinshasa. At club Why Not, Six and his friends have arrived. The bass from this club, and from dozens of clubs all around, is thumping away like heavy rain. We go in and immediately the DJ is shouting to the Sapeurs. Somebody buys a bottle of whisky. And the Sapeurs and the Congolese who love them are in the mood. They're set to dance all night.

Photos by Manuel Toledo

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and Thursdays at 11:02 GMT

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule.

For more on the BBC's A Richer World, go to www.bbc.com/richerworld- or join the discussion on Twitter #BBCRicherWorld, external

More from the Magazine

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.