Missing the old Gypsy orchestras

- Published

People speak of the "Roma" thinking it's polite, but when it comes to music, the old word "Gypsy" is much more widely used, and many Roma today are proud of their Gypsy music traditions. But how much of that music is left in the modern world?

Antal Dragic - known as Uncle Tony to his friends - is feeding his pigeons when I arrive. It's a typical Balkan scene at dusk - a crumbling single-storey house, backing onto a courtyard, with a gnarled pear or plum tree in the middle, a pile of half-chopped wood, a lazy cat asleep on top of an old cupboard, and a sudden flurry of wings.

He leads me through his kitchen, past a parrot and a photo of himself on the wall, much younger, in an ironed white shirt, cradling a double bass.

Installed on an ancient sofa, he takes me through a pile of black-and-white photographs, of the Gypsy orchestras of yore. "I turn on the radio now," he laments, "but there's no music worth listening to. If the old guys were to wake from the dead, and hear this trash, they'd smash their instruments!"

Antal Dragic (Uncle Tony)

Uncle Tony is a Gypsy, and proud of the name - one of the last survivors of the great dynasties of Hungarian Gypsy musicians in Subotica, a town in the north of Serbia. This was the capital of Hungarian Gypsy music in the old Yugoslavia - they gloried in a country where every restaurant worthy of the name had live music until dawn.

"When I was born, my grandmother put a bow in my hand, and that's how I came to play the double bass," he explains. There were several streets where only musician families lived. Tony had his own band from the age of 14. The children gathered each afternoon in the streets with their violins. They knew the birthdays of all the prominent people, and serenaded outside their homes, in the hope of food, drink, or small change for cinema tickets.

That music has all but died out now, he laments. "There's no demand for it in the restaurants, and those who once sponsored it, the managers of the big restaurants and hotels, are no longer with us."

Hungarian folk music and Hungarian Gypsy music overlap - though just how much is a matter of controversy. When the composers Bela Bartok and Zoltan Kodaly set out through the countryside collecting folk music at the beginning of the 20th Century, the villagers told them they would fetch the Gypsies to play it for them. "No, we don't want to hear Gypsy music, we want Hungarian music," cried the composers. "But only the Gypsies can play it," explained the exasperated peasants.

The music the tribes of Gypsies brought with them as they straggled across Europe from India in the Middle Ages, was strongly influenced by the music of the countries they passed through. They became masters of it all, developing a Gypsy style of their own. That thrived under the patronage of the landed gentry between the wars, was revived under Communism, but is now withering on the vine.

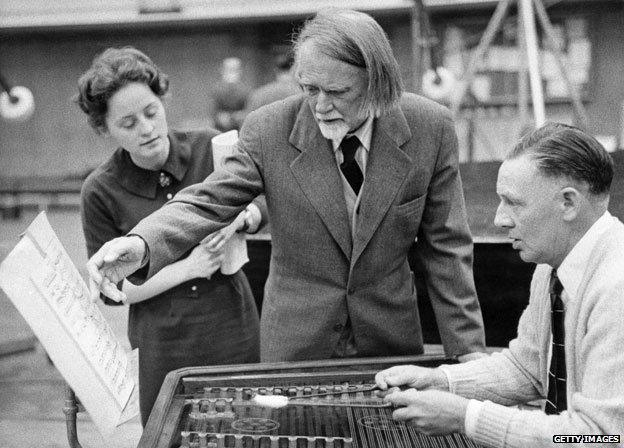

A band of Hungarian gypsy musicians

Miki Lukacs guides me round the Talentum Rajko building, near Budapest's East Station. He's probably Hungary's most famous player of the cimbalom, a sort of hammer dulcimer, which looks a bit like the inside of a piano and is played with astonishing results with two rods with what looks like candy floss on the ends. This was the building where, from the mid-1950s, the Communist authorities encouraged Gypsy music. Young children were brought here from poor villages and taught music, discipline, and foreign languages, and when they finished they were guaranteed a job. The state-run National Entertainment Centre allotted them a restaurant, night after night.

And the grand boulevards of Budapest swarmed with restaurants in the 1960s and 70s. Under Communism, an average Hungarian family could afford to eat out once a week, and the fiery music on offer was as important as the fiery dishes, washed down with ample quantities of brandy and wine. That world died overnight with the return of capitalism. The new owners cut costs, and families couldn't afford the new bills. Some musicians found refuge in jazz, Miki explains. But about half gave up music altogether, he reckons. "And got jobs as security guards, or parking attendants."

Zoltan Kodaly, his wife Sarolta and a cimbalom player rehearsing the Harry Janos suite in 1960

A good proportion of Hungarian jazz musicians today are of Roma origin. There's a famous 100-member Gypsy orchestra in Budapest, and bands of Hungarian Gypsies still play the ballrooms of luxury cruise liners - and roam the decks, looking nostalgically homewards to their land-locked country. And music schools try to teach young musicians to present their talents on social-media, as well as on stage.

"Music opens your soul to another world," says Miki Lukacs. It can also heal the one you're in. As a child he suffered from terrible migraines. A thoughtful doctor prescribed the cimbalom - his father's instrument. The sweet sound of the hammers on the metal strings dissolved the pain.

Black and white photographs courtesy of the Lakatos family archive, Subotica

Nick Thorpe's seven part documentary film series on Roma communities across Europe - A Gadjo in Romanistan - begins 16 March on Duna TV

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and Thursdays at 11:02 GMT

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.