How did the UK get the 30mph limit?

- Published

Eighty years ago the UK reintroduced a 30mph speed limit in built up areas. With calls to reduce the limit, Chris Stokel-Walker looks at its history and future.

Today there are three typical speed limits across the UK:

a 30mph limit on roads with street lighting (which is taken to indicate a built-up area)

a 60mph national speed limit on single carriageways

and a 70mph top speed on dual carriageways and motorways

The limits are meant to keep everybody safe. The Department for Transport (DfT) says that for every 1mph the average speed of vehicles reduces on roads, there are 6% fewer accidents.

Speed limits should be "evidence-led and self-explaining", the DfT explains, and "should be seen by drivers as the maximum speed rather than as a target speed at which to drive irrespective of conditions".

Today road safety in the UK is relatively good, with one death on the roads for every 20,000 cars.

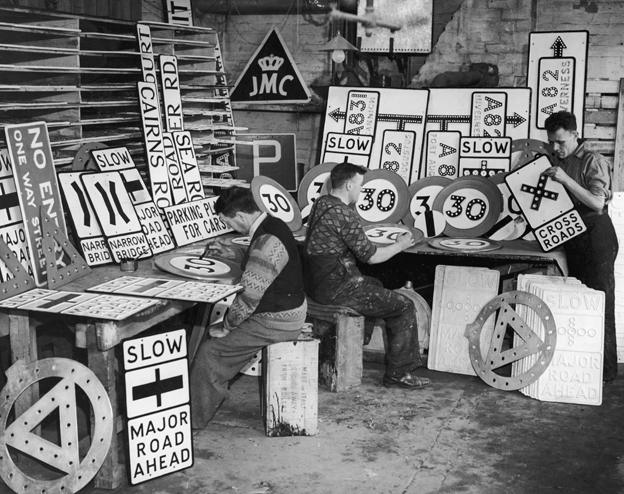

1935: Sign writers prepare for the introduction of speed limits

Back in 1934, just prior to the introduction of the 30mph speed limit, there were only around one-tenth of the cars on the road today, but four times as many associated deaths.

There had previously been a blanket 20mph speed limit, set in the 1903 Motor Car Act, but it was repealed for light vehicles in 1930. The spate of deaths caused a change of heart in government in 1934 and 1935, with 30mph brought in for built-up areas.

In the days before the implementation on 18 March 1935, MPs debated the benefits and drawbacks with unusual prescience given the issues today.

Motorway speed limits around the world

United Arab Emirates: 120km/h (75mph)

USA: varies between states - 104-136km/h (65-85mph)

Sweden: 120 km/h (75mph)

China: 120km/h (75mph)

New Zealand: 100 km/h (62.5mph)

Germany: Advisory limit of 130km/h (81mph)

Sir Oliver Simmonds, Conservative MP for Birmingham Duddleston, asked the home secretary of the time, Sir John Gilmour, whether exceeding the limit by two or three miles per hour would be overlooked by the police.

"No, sir," came the reply from Gilmour. "Ample warning is being given of the procedure which will be followed by the police, and I hope that the motoring public, by their general observance of the intentions of parliament, will render unnecessary any frequent recourse to proceedings on the part of the police."

But it seems rather than basing their decision on hard evidence, officials and politicians settled on 30mph in a rather arbitrary fashion.

"It was pulled out of a hat," says Rod King, founder of the 20's Plenty for Us campaign, which believes that the 30mph limit today is no longer appropriate, credible or acceptable.

In 1935, Motorsport Magazine was sceptical. "Conditions vary so widely that any attempt to secure uniformly safe driving by a single speed limit is bound to result in failure," the magazine wrote.

By the big day in 1935, some of the infrastructure, including key signs indicating the speed limit of a road, wasn't in place in some areas. Pieces of paper plastered over existing signs, or on tin discs, were occasionally used. Those official signs that were erected were torn down and thrown in lakes in some areas, so unpopular was the new law.

There is still controversy. Campaigners seeking more protection for cyclists and pedestrians want the 30mph limit reduced, with 20's Plenty for Us favouring a drop to 20mph - the original speed limit from 1903 - in all built-up areas.

"The 30mph limit is compromised beyond belief," says King. Cities including London, Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol, Bath, Cambridge, Liverpool, Oxford, Brighton, Newcastle and Edinburgh, have introduced 20mph limits on some roads in their jurisdiction. The Lib Dems have even considered 10mph limits in some areas, external.

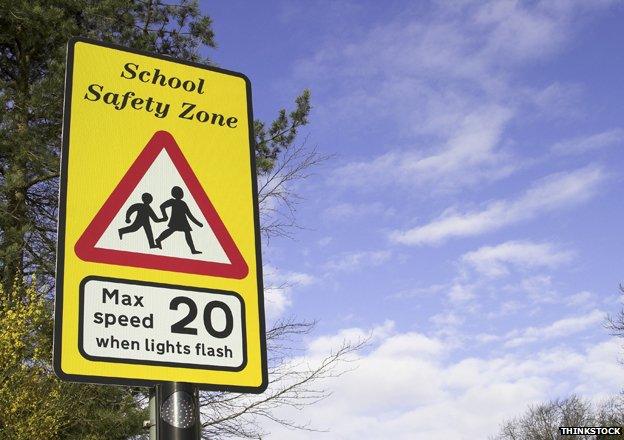

While motoring organisations the RAC and the AA have expressed support for 20mph limits outside schools, they oppose a blanket change from 30 to 20.

And there are drivers' groups who believe the whole idea of rigid speed limits may not actually improve safety. "Speed limits are supposed to give the driver an indication of what sort of hazard level he is going to be exposed to on the road," argues Brian Gregory, chairman of the Alliance of British Drivers (ABD), a lobby group. "Now they've become a master rather than a slave, and adherence to a number on a piece of tin has become the primary criterion in road safety whereas actually it shouldn't be."

The argument of Gregory, and many drivers like him, is that speed limits that are poorly set can actually increase the likelihood of accidents. Drivers become too focused on their speedometers rather than the road around them, they argue.

Gregory believes that limits should be set according to the 85th percentile principle - traffic speeds should be measured under free flow conditions, and the limit set so that only 15% of the traffic will exceed the limit. According to him, some roads now are being set so that 50% of traffic flowing freely exceeds the road's speed limit.

As speed limits have fallen, so have road deaths, admits Gregory. But he doesn't think there's a causal relationship. "Road engineering, better cars and better brakes have brought about the decrease in deaths, not speed limits," he says.

"Speed limits in themselves have a limited effect," agrees Dr Joanne-Marie Cairns, a post-doctorate research associate in public health geography at Durham University. But Cairns is in favour of a 20mph limit.

"Reducing speed alone will not solve a lot of the problems on the roads," believes Cairns. "They have an effect, and up to a 25% reduction in casualties, but to see the most promising effects we need to go beyond that." The benefits, she says, are clear - pedestrians and cyclists feel safer taking to the streets when cars go slower, and so people take more exercise.

It may not be a central issue in the coming election, but after 80 years the debate on speed is nowhere near being settled.

More from the Magazine

When German politician Sigmar Gabriel suggested a speed limit on all stretches of German autobahns, there was a collective drawing-in of breath and raising of eyebrows. Why, many wondered, would a politician trying to win votes suddenly come up with a proposal so clearly doomed to lose them?

Germany's love of life in the fast lane (May 2013), external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox