Michael Mosley: Why I consumed my own blood

- Published

Michael Mosley with his blood sausage

Human blood is an extraordinary substance that manages simultaneously to nourish, sustain protect and regenerate our bodies, but despite decades of research we are only just beginning to exploit its full potential. Michael Mosley has been putting his own blood through a series of rigorous tests.

In 1897 Bram Stoker's Dracula was published, helping fan an interest in blood-drinking human vampires that has never gone away. In the novel, Count Dracula feeds on human blood and transforms himself from a little old man with white hair into a dark-haired super-athlete.

Stoker's novel, and others that came before it (such as "Carmilla", a novel about a lesbian vampire) were in turn inspired by centuries of mythology that have surrounded blood, mainly focused on its alleged powers to heal and restore.

In Roman times the sick, particularly epileptics, were encouraged to attend gladiatorial combats in the hope that they would be able to cure their illnesses by drinking the blood, external of a freshly killed gladiator

In later centuries, medical practice focused more often on blood letting than blood consumption, but the belief in the power of blood to restore and rejuvenate persisted.

Bloodletting

Bloodletting was a common medical practice for nearly 2,000 years

In medieval times, the person who cut your hair and gave you a shave also did the bloodletting

On barber poles the white represents fresh clean bandages, and the red represents blood

Originally you'd have had a basin on top to hold the leeches, and one underneath to hold the blood

George Washington, first president of the US, is just one of many people bled to death by their doctor

Draining "overheated blood" from a patient deprived them of critical infection fighters - white blood cells

A 16th century Hungarian Countess, Elizabeth Bathory, is said to have bathed in the blood of 650 slaughtered virgins in the hope that their fresh blood would somehow help her cling on to her own fading youth.

This is clearly nonsense. Or is it?

Blood transfusions have been saving lives for decades and blood itself is certainly extremely nutritious. To demonstrate, I decided to make a blood pudding out of my own blood and then eat it. Rich in iron, protein and vitamin C, it is also quite calorific. In fact there's almost twice as many calories per ml of blood as, say, beer.

Preparations for the blood pudding

But the legends claim that fresh blood can do far more than simply nourish us - that it has a transformative power. And modern science - at least when it comes to transfusions - seems to back that up.

A few months ago I met Dr Saul Villeda, a biologist at the University of California, who has been doing some extraordinary research looking at what happens if you inject blood from young mice into old mice. This is not being done simply to replace elderly blood but to transform it.

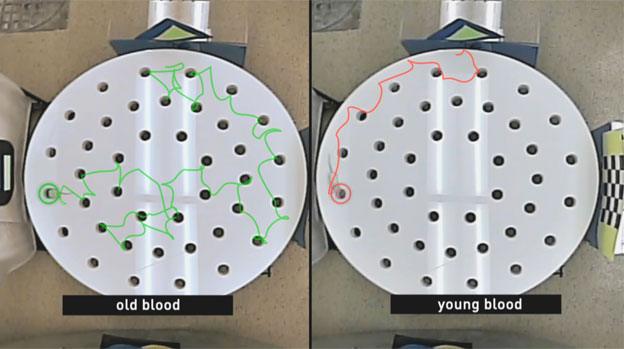

After an infusion of young blood the old mice perform significantly better in memory tests, such as finding their way through back to their nest.

Find out more

The Wonderful World of Blood with Michael Mosley will be broadcast on BBC Four on Wednesday 25 March at 21:00. You can catch up on BBC iPlayer.

The effects of young blood on elderly brains is particularly striking when you look at the brain cells themselves. When mice - like humans - age, the neurons end up looking like tired, shrivelled peanuts.

Once the brain cells from an elderly mouse have been infused with young blood, however, they start sprouting new connections to fellow neurons and become much more like those of a young , smart, mouse.

The mouse on the right received young blood and found a direct route back to the nest

Villeda thinks that something in young blood triggers increased activity in the stem cells of old mice, cells that then give rise to new, younger neurons.

Although most studies so far have been done in rodents, trials have begun at Stanford University in which patients with early signs of Alzheimer's get infusions of blood from young volunteers. So can Villeda imagine a time when elderly people with fading memories are regularly infused with blood from young people?

"My hope," Villeda says, "is that we can identify the youthful factors in blood that we want to raise and the ageing factors we have to lower. And I think that'll be a much better way, a much more controlled way."

Understandably I wasn't allowed to take part in the trial and my children were strangely reluctant to donate their blood, so instead I tried a different form of blood-based rejuvenation therapy - an infusion of PRP (platelet rich plasma), more popularly known as the Vampire Facelift.

Championed by the likes of Kim Kardashian, it consists of taking your own blood, spinning it down, extracting the plasma and and injecting it back into your face. Strange as it sounds, the use of PRP to heal and repair is currently a very hot area of scientific research.

Janet Hadfield, director of a company called Biotherapy Services, which does research into PRP, says that PRP has been used for years to promote wound healing and to treat sports injuries. Fans are said to include the golfer Tiger Woods and the tennis player Rafael Nadal.

Michael Mosley gets a Vampire Facelift

More recently there have been trials of PRP at the Royal London Hospital to see if it will help to speed up wound repair in type-2 diabetics, who are particularly prone to developing wounds that won't heal. The results so far suggest it does.

No-one is sure how it works, but a study published some years ago, external in the Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery found that extracting plasma by centrifuging it leads to the release of significant levels of growth factors which may promote wound healing and collagen growth.

When I asked Hadfield what changes I could expect, she replied: "After a couple of weeks you should be able to feel a difference in the tone and texture of your skin. Hopefully it will become more like a baby's bum."

So I did it and a couple of weeks later, just as promised, there were some subtle changes. But it is expensive and the improvement was not impressive enough to make me want to do it again.

Nonetheless, after doing a range of other fascinating experiments, I was left with a huge respect for this very special fluid.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.