The Jeremy Clarkson story

- Published

Jeremy Clarkson will not have his contract at the BBC renewed, in the wake of allegedly punching a producer. But how did he get to where he is now?

"In the competition between fame and fortune, you'd take fortune every day of the week," Jeremy Clarkson once said. "Fame is almost constant pain."

But the 54-year-old has made a career from being publicly controversial. The Top Gear host has managed to offend Argentines, Germans, Mexicans, Romanians and a host of others. Known for a fashion-proof love of tight denim, he's a friend of Prime Minister David Cameron and writes columns for two national newspapers.

Born Jeremy Charles Robert Clarkson in Doncaster, South Yorkshire, on 11 April 1960, to art teacher Shirley and travelling salesman Eddie, the star has described his early family life in a 400-year-old farmhouse as happy.

Clarkson first worked for the BBC aged 12, playing the role of Atkinson in the radio adaptation of the Jennings novels, Anthony Buckeridge's tales of life at the fictional Linbury Court preparatory school. The role did not last long.

1972: Anthony Buckeridge and the cast of "Jennings" - no prizes for recognising the young Clarkson

"Why did it come to an end?" Top Gear co-host Richard Hammond once asked in an interview on LBC Radio. "He will have done something stupid, obviously." The truth was actually more prosaic. Clarkson's voice broke. Uttering schoolboy slang like "wizard" and "blinko" did not work in baritone.

Shirley and Eddie put Jeremy's name down for a number of public schools with apparently little idea of how to pay the fees. "They really didn't want me going to the local state school in South Yorkshire, which was rough," Clarkson once told BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs.

Not long before Jeremy turned 13, the age at which he was due to become a boarder at the family's first-choice school, Repton, in Derbyshire, Shirley hit on a lucrative idea.

She made toy versions of Paddington Bear for Jeremy and his sister Joanna for Christmas. They proved popular with friends, so she and her husband started selling them. But lawyers for Paddington's creator, Michael Bond, weren't happy, at one point threatening litigation. So Shirley, who wrote about the episode in a book, external, and Eddie spoke to the author to seek out the licensing rights.

"It was the start of my good fortune, really, which has followed me all the way through life," Clarkson told Sue Lawley. "They just happened upon Paddington, just as I was getting to 13, so I was able to go away and the school fees were able to be paid."

Yet school did not turn out as Clarkson's parents had hoped. Living away from home meant "suddenly I found out that I could misbehave without the embarrassment of a parent finding out. A teacher finding out - who cares really? Who cares that your English teacher knows you've had a fag?"

"When you're young, you never guess which people are likely to make themselves into world-renowned figures," fellow ex-pupil Jerry Austen told the Sunday Times, external. "Certainly, Jeremy wouldn't have sprung to mind."

While Clarkson succeeded academically, passing nine O-levels, his behaviour was poor. He smoked, drank and, despite the restraints of a single-sex school, womanised his way out of Repton, the story goes. Ten weeks before sitting his A-levels, he was asked to leave. There is some debate as to whether this constituted a full expulsion or merely an agreed parting of the ways.

Out of education, Clarkson, by now 6ft 5in tall with dark, curly hair, had little to do other than return to his parents and help with stuffing bears. "They were so cross with me," he said, "but I knew something would come along. Something always comes along. It does in my life, anyway."

Walking along the street one day, he came across the general manager of the local paper, a family acquaintance, who asked him what he was doing there. After explaining his expulsion, the man replied that he should become a journalist.

Clarkson got an interview at the Rotherham Advertiser, where, according to his own account, further good fortune followed. The CV was sparse, but it turned out that Clarkson's grandfather, a GP, had delivered the editor's first child, having come out during a World War Two air raid to do so. Still grateful, the editor offered him a job.

Although now a fluent writer, Clarkson described himself as "properly rubbish" at local reporting, once forgetting the reason he had phoned a bereaved woman and, on another occasion, being forced to leave an inquest in hysterical laughter while messing around with a colleague.

"He was very much the same as he is now," sports reporter Les Payne, who shared a desk with Clarkson at the Advertiser, says. "He was a younger version of the current Jeremy Clarkson you see on TV. He mucked in with the rest of the office but he was very much a man who expressed his own opinions."

Payne remembers a colleague little interested in the goings-on in Rotherham, at one point bridling at having to cover an agricultural show. "He was taking the mickey," he says. "He didn't like having to write down which was the biggest marrow. The parish pump stuff clearly didn't appeal to him."

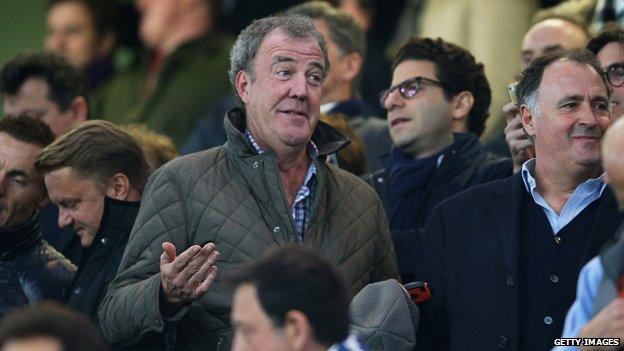

Clarkson is now a regular attender of Chelsea matches, but didn't always express enthusiasm for football. "He used to say all sport, except motor sport, was a waste of time, and that football was no more than kicking a windbag around a field and pointless," says Payne. "So I'm not sure when all that changed."

But one constant is Clarkson's love of cars and driving. When Payne wanted to buy his first car, Clarkson spoke to his girlfriend and she sold her yellow Mini to him.

Clarkson watching Chelsea play PSG at Stamford Bridge, March 2015

In 2011, the BBC received more than 20,000 complaints after Clarkson joked on The One Show, external of public sector workers striking over pensions: "Frankly, I'd have them all shot. I would take them outside and execute them in front of their families." But, says Payne, Clarkson also went on strike during a pay dispute in the late 1970s, although he can't remember him joining the picket line.

Clarkson left the Advertiser and worked for the Rochdale Observer and Wolverhampton Express and Star, but realised life in provincial journalism was not for him. He went home to his girlfriend one night and experienced an epiphany midway through telling her about the installation of some new office furniture. "I knew at that moment that I had to leave," he told Desert Island Discs, "because when new office furniture becomes so important that you even mention it, pack your bags, get out, move 200 miles away."

He went south, still looking for a role in life. "I couldn't really work this notion of working for someone else. I was living in Fulham in south-west London, a real Thatcher heartland, and everybody had their own little business doing up houses, a million different things, print shops and so forth. And I thought I've got to have one of these little businesses. So I forced myself to have an idea a day."

Playing on his love of cars, he started his own company, Motoring Press Agency, providing reviews to be syndicated among the regional press. From here, he became a regular contributor to Performance Car magazine.

At a Citroen product launch in the New Forest in 1987, Clarkson began talking to Jon Bentley, external, a researcher on Top Gear, the long-running BBC Two car magazine show.

Jeremy Clarkson and fellow Top Gear presenters in 1992

"He was just what I was looking for - an enthusiastic motoring writer who could make cars on telly fun," Bentley, who now hosts Channel 5's The Gadget Show, has said. "He was opinionated and irreverent, rather than respectfully po-faced. The fact that he looked and sounded exactly like a twenty-something ex-public schoolboy didn't matter. Nor did the impression there was a hint of school bully about him. I knew he was the man for the job."

A few months later, Bentley, now promoted to producer, was able to offer Clarkson a screen test, in which he road-tested a Range Rover. "Clarkson stood out because he was funny," Bentley has said. "Even my bosses allowed themselves the odd titter."

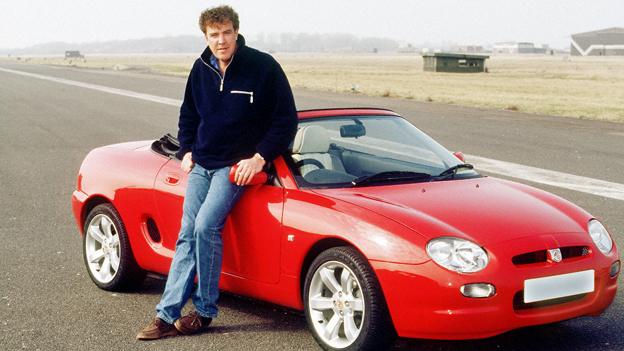

Clarkson first appeared on Top Gear, which had been going since the 1977 as a straight car magazine show, in 1988. In an echo of his trip to the agricultural show in Rotherham a decade earlier, one of Clarkson's first assignments saw him reporting on a junk sale, in a style free of irony. His initial performances were, by his own admission, rather wooden.

But he became more relaxed and outspoken and he changed his appearance, going from wearing blazer, tie and chinos to his now signature outfit of jeans and casual jacket. Clarkson was highly critical of some cars, external. "We spent most of the time filming it from the back so as not to frighten viewers," he said of the Ford Scorpio. On the Vauxhall Vectra, he told viewers: "I have to fill seven minutes with a car that doesn't merit seven seconds."

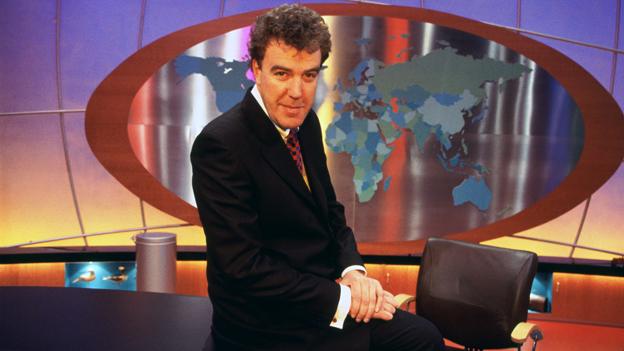

BBC executives liked what they saw. In 1998 the chat show Clarkson started on BBC Two. It played on Clarkson's growing reputation for plain-speaking, allowing him to goad celebrities. "There are no transsexuals in Chipping Norton. That's just a fact," he said during an interview with the feminist writer Germaine Greer. In one skit, he put a 3D map of Wales in a microwave oven.

Clarkson's chat show ran until 2000 - it "tanked" according to one commentator

"It's regarded as a significant achievement to get a chat show," says media commentator Steve Hewlett. "When someone moves from their area of expertise, it's a signal that they're able to exert pressure. If you talk to people on the commissioning side of TV, they say there are lots of agents pushing for their clients to get a chat show." Unfortunately, says Hewlett, the programme, which came off-air in 2000, "tanked".

Clarkson left Top Gear in 1999, describing Birmingham, where the show was then filmed, as "the armpit that masquerades as Britain's second city", external. He even suggested his own style had grown tired, writing in Top Gear Magazine: "The shock tactics had become predictable and so weren't shocking any more."

"The first time you heard me liken some car to the best bits of Cameron Diaz," he added, "you probably sniggered about it at school all the next day. But now, it's tedious."

The Clarkson-less Top Gear was taken off-air in 2001 for a revamp. It returned the next year with Clarkson as the main presenter, after he and fellow Old Reptonian Andy Wilman, a producer, devised a different, mainly studio-based format, focusing on banter between presenters.

Clarkson's first co-hosts of the revamped show were Richard Hammond, who had worked on cable TV, and former car salesman Jason Dawe. For the second series, Dawe was replaced by James May, an experienced motoring writer.

The show soon gained a cult status. Items like Star in a Reasonably Priced Car were interspersed with studio discussions, slickly filmed car reviews and stunts and races. Items showing Clarkson, May and Hammond going around the world, getting into scrapes, proved popular.

"The reason you like it is [that] the relationship between the three presenters exactly mirrors the power structure of the relationship of the three bears," comedian Stewart Lee joked.

A silent, helmeted character called The Stig, his true identity unknown, joined as the show's test driver. The name was apparently an in-joke between Clarkson and Wilman, Stig being a nickname for first-year pupils at Repton, external.

The clubby new atmosphere worked. Top Gear became a hit not just in the UK, but much of the world. It is sold to 214 countries, has an estimated global audience of 350 million and reportedly makes the BBC £50m a year, external. Clarkson sold his stake in the Bedder 6 joint venture - which exploited the commercial rights to Top Gear - to BBC World in 2012 for £8.4m, external.

Clarkson lives near the small town of Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire. His friends from the area include David and Samantha Cameron, former Sun editor Rebekah Brooks and Blur bassist Alex James. The press has nicknamed this group the "Chipping Norton set". In 2010, Cameron reportedly appeared dressed as The Stig, external for a video filmed as part of Clarkson's 50th birthday celebrations.

A smoker since his school days, Clarkson has campaigned against the ban in enclosed public places, including bars, and is a frequent critic of bus lanes and the European Union.

Partly because of his friendship with Cameron and his dismissal of former Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown, external as a "one-eyed Scottish idiot", for which he later apologised after a barrage of criticism, it is often assumed that Clarkson is a Conservative, but he rarely comments on party-political issues. His role is seen by some as more of a tribune of disgruntled middle England.

Clarkson attended Lady Thatcher's funeral in 2013 (pictured with Lady Lloyd Webber and his daughter Emily)

Clarkson has had a long-running feud with former Daily Mirror editor Piers Morgan, whom he punched at the British Press Awards in 2004 for publishing photographs of him with a female colleague.

Arguments and controversy are never far away. In 2008, the BBC received hundreds of complaints after Clarkson made a joke about lorry drivers murdering prostitutes.

In 2010, the show upset Mexicans by branding them "lazy, feckless and flatulent". In July last year, the broadcasting watchdog Ofcom censured the show after Clarkson used a derogatory term for Asian people during a Burma special.

And, in May last year, Clarkson revealed he had received a final warning, and faced the sack if he made "one more offensive remark, anywhere, at any time". This followed the dissemination of a clip, filmed in 2012 but not used on Top Gear, in which he appeared to use the "n-word". He apologised.

Other groups are considered fair game, though. "You can only be racist about people who have been persecuted," he once said, "and, I'm sorry, that doesn't include the Germans or the Americans."

Clarkson has had two marriages. His first, to Alexandra James in 1989, external, lasted only a few months. In 1993 he married his manager, Frances Cain. They have three children.

Clarkson bought a converted lighthouse on the Isle of Man's Langness peninsula, but he and Frances became involved in a seven-year legal dispute with ramblers over a path running near the property's kitchen. In 2012, a judge ruled in favour of the ramblers. Frances described the ordeal as a "horrible experience".

Now in his mid-50s, Clarkson remains as controversial as ever. Will he temper his act? Does the vitriol he gets in return sometimes hurt too much?

Up to his waist: The Top Gear Burma special was one of several occasions where Clarkson attracted controversy

"Of course you mind," he said on Desert Island Discs. "You do mind... In the wee small hours you do think, 'I wish I were a nicer person. I wish I could be nicer about people and things.'

"But then in the heat of the moment, perhaps a month later, when you've perhaps had too much coffee, and you're in the studio and something crops up and you say something and everybody laughs and you feel great and you go home and actually you've upset somebody else."

The Sunday Times TV critic AA Gill, a close friend of Clarkson, has written that he does not feel appreciated by the BBC, that he has been "working for the enemy", external, while dealing with the loss of his mother and some health issues. David Cameron has also supported him, saying: "Because he is such a huge talent and he amuses and entertains so many people, including my children, who'd be heartbroken if Top Gear was taken off air, I hope this can be sorted out, because it's a great programme and he's a great talent."

Whatever happens, having already earned millions, Clarkson will not struggle for money. And his fame, however painful for him, is unlikely to diminish either.

More from the Magazine

It's hard to go anywhere in the world these days and not find that Top Gear has got there before you. The programme may have begun on regional television in the UK - but it's now viewed in pretty much every region of the globe, writes Daniel Silas Adamson.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox