The online dating site sued for targeting married people

- Published

An online dating site that targets married people is being accused of breaking the law. A court in France must now decide whether the company is illegally encouraging spouses to cheat.

Is it permitted for a dating website to promote adultery, when fidelity in marriage is written into French civil law?

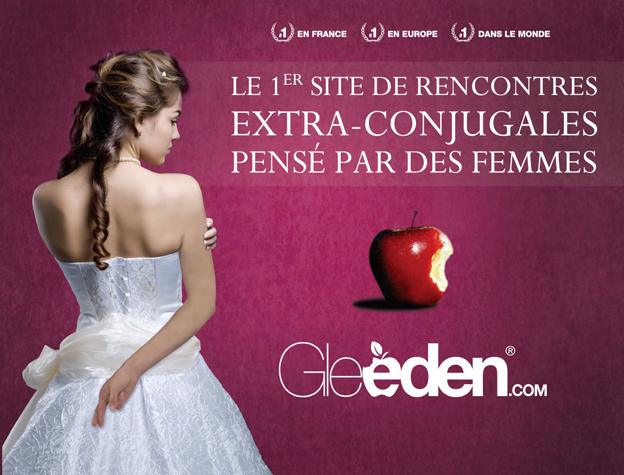

That is the question underlying a law-suit targeting the French company Gleeden, which boasts that it is the world's leading "extra-conjugal site conceived for married women".

Angered by Gleeden's provocative advertising on the public transport system, the Association of Catholic Families (ACF) has filed a civil case contesting the site's legality.

It might seem odd in this permissive age, but family lawyers agree that the ACF plea has a respectable chance of succeeding.

This is because the notion of fidelity as constituting an integral part of marriage is specifically spelt out in the French civil code.

In France, all law is based on written codes (penal code, labour code, commercial code etc) which can be amended by parliament. Judges are free to interpret the codes, but their room for manoeuvre is much more limited than in a common law system like the UK's.

And in Article 212 of the Civil Code, it states: "Married partners owe each other the duty of respect, fidelity, help and assistance."

"There are plenty of other websites out there which promote sexual contact between individuals, but what makes Gleeden different is that its very business model is based on marital infidelity," says Jean-Marie Andres, president of the Association of Catholic Families.

"It states quite openly that its purpose is to offer married women opportunities to have sex outside the marriage.

"But here in France, people and parliament are all in agreement that marriage is a public commitment. It's in the law. What we are trying to do with our suit is show that the civil code - the law - has meaning."

Gleeden does not demur from the accusation that it is aimed at married women. Far from it. Married women are its unique selling point.

The advertisements which caused such horror among conservatives and Catholics blatantly encourage wives to think that cheating is both permissible and fun.

One poster displayed on buses and metros shows an attractive young woman in a bridal dress with her fingers crossed behind her back. The message is clear: vows are for suckers.

Founded in 2009, the website says it has 2.3 million members in Europe including one million in France. It has smaller operations in the US and other countries.

Under the Gleeden model, women do not pay to be registered on the site. Men buy credit, opening up different levels of access to registered women. Though accurate information on this is impossible to obtain, Gleeden says 80% of the people who use it are indeed married.

Margot, a Parisian aged 44, is one such user. She has been married for many years, but says she is unsatisfied sexually. However she has no intention of leaving her husband.

"I chose Gleeden precisely because it is for married people. It means that the person you meet knows your situation. There's no deception. We can talk openly about husbands, wives and children.

"Also when we are both married, we both accept we only want to go so far in the relationship. It's easier to keep things uncomplicated. We respect each other's private life."

Margot admits however that most of the men she has met via Gleeden have been sub-optimal. "Nearly all of them have been charlatans," she says.

And she understands why some people might be shocked by the way the website promotes itself.

"Let's face it - it is promoting infidelity. In fact, it's selling infidelity. It's making money out of it. People could easily be pushed into the act after seeing those advertisements," she says.

"But let us not be hypocritical. It's not black and white. In most marriages at some point there is infidelity, but that does not mean the marriages collapse. Sometimes the infidelity is what saves the marriage."

Gleeden representatives make a similar point. "We have plenty of clients who tell us that having a secret garden is what saved them from walking out of the marriage," says spokeswoman Solene Paillet.

But her main argument is free speech. "We didn't invent adultery. Adultery would exist whether we were there or not," says Paillet.

"All we are doing is filling a demand. If people see our advertisements and are shocked, well there is no obligation. If you see a nice car in an ad, you aren't obliged to buy it. You make your own mind up."

Lawyers say that the AFC case is far from frivolous. Article 212 does have force in law.

"Juridically speaking, the case has a solid base. By organizing relationships between married people, it is possible to argue that Gleeden is inciting couples to violate their civic duty," says Stephane Valory, a specialist in family law.

"However there is no certainty about it. In a case like this the courts will also take into account the changing moral values of modern society. The notion of a duty to fidelity is quite loose.

"Fifty years ago many more people would have been shocked by what Gleeden is offering. Today it is only a minority who notice. So the courts will certainly not rule in the same way as they would have 50 years ago."

That may well be true because 50 years ago the old penal code was still in force, which made adultery an actual crime. Under the 1810 code, a woman caught in adultery could be imprisoned for up to two years - while a man received only a fine!

In fact the clause had long been a dead letter before it was abrogated in 1975.

Today - especially after the Charlie-Hebdo attack - a far more sensitive issue in France is the encroachment of religion into public life.

The separation of religion and state is held as a supreme good, and courts may look askance at a plea motivated by Catholic abhorrence.

On the other hand the lack of checks on 21st Century permissiveness is arguably a factor pushing some to religious fundamentalism.

The judges shall decide.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.