The ancient city that's crumbling away

- Published

The ancient city of Mohenjo Daro was one of the world's earliest major urban settlements - but as Razia Iqbal found on a recent visit to Pakistan, its remains are in danger of crumbling away.

As a lover of language, I am convinced that certain combinations of letters have in them some innate magic - like Kubla Khan, or Xanadu, or Nineveh. So allow the words Mohenjo Daro to roll slowly off your tongue. And let me tell you about this ancient city, rediscovered nearly 100 years ago, but which had its heyday 4,000 years ago.

It lies on the banks of the River Indus in the province of Sind, in Pakistan. Along with another historical site, Harappa, it represents the very earliest civilisation in the region, rivalling those in Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Mohenjo Daro was a city which had been effectively planned and boasted exceptional amenities. Its houses were furnished with brick-built bathrooms, many had lavatories. Waste water from these led into well-constructed sewers that ran along the centre of the streets, covered with bricks.

Among the many artefacts unearthed here, and one which stays in my mind, is a tiny, 10cm-high, bronze statuette. She's known as the dancing girl - a poised figure, with hand on hip, and face thrusting forward. She tells us not just about the Indus people's skills in metallurgy but also about their art, society and women as well.

Given Mohenjo Daro's archaeological importance - it is a Unesco World Heritage Site - I was saddened to find it in some disarray.

Tourism and heritage aren't high on the government's agenda here. The authorities are far more preoccupied with security and terrorism.

It was not what I would call a busy tourist destination, few Pakistanis visit and we were among just 20 or 30 people there. We walked around the small museum which, though full of interesting exhibits, was badly lit and poorly arranged. Outside the dancing girl is displayed. But it's not the original. That's now in Delhi.

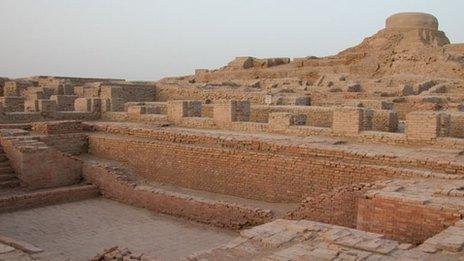

We walked to the city itself. It's a wonder in so many ways, a vast site of neat, fired-brick structures, identifiable streets and a place where it's easy to imagine what life was like for its 35,000 inhabitants.

Remarkably, only a small part of it has been excavated. One of our party, Maha Khan Philips, is writing a fantasy thriller which is set in the ancient city. She wonders if all of it should have remained buried in order to preserve it.

So much of what you can see is crumbling. Exposed walls are falling apart from the base up. That's because salinity in the ground water is destroying the bricks which, before they were unearthed, had survived for thousands of years.

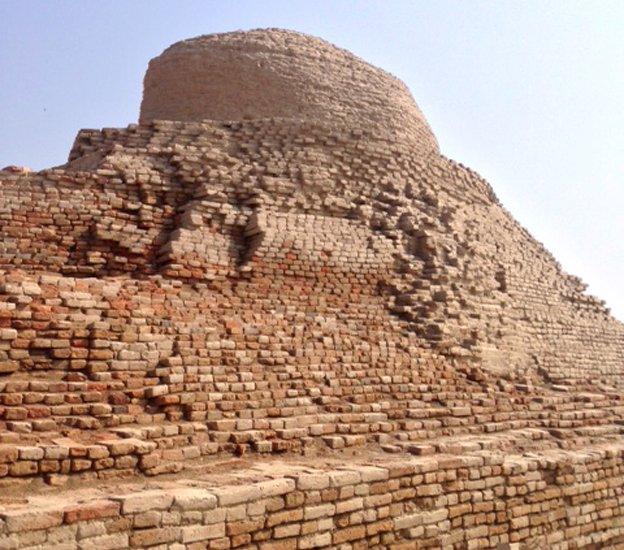

But it's still an extraordinary site. There's a large brick Buddhist stupa at its centre. Mohenjo Daro means Mound of the Dead. A picture of it graces Pakistan's 20 rupee banknote.

Zain Mustafa, who now lives in Pakistan, mused that Mohenjo Daro has much to teach the country today. A nation which appears to define itself from 1947 onwards, as a Muslim country, he feels, could find much to celebrate in the achievements of this ancient city.

But it's hard to believe anyone's taking proper care of a place which has such valuable things to teach us about urban planning and a country's history. Perhaps it should be given over to the care of external conservationists. Certainly the news of the recent wanton destruction of ancient sites in the Middle East has made many wonder about the need for protection here.

There were no guides at Mohenjo Daro the day I was there, no one running after us. There were no postcards, no souvenirs, no leaflets about the site. There were a couple of intelligence or security-type fellows with guns who seemed particularly interested in the foreign passport holders in our party. I ignored them as we listened to my companions, who said some archaeologists think, given the current rate of crumbling, the site will not exist in two decades.

I heard the theories about what could have destroyed this civilisation so many years ago: a violent massacre perhaps, or flooding and disease, or even more fantastic, some kind of explosion, a fireball or meteorite. And now it's being destroyed by something quite banal - neglect and a lack of interest.

Next year, a Bollywood film of some considerable scale, called, simply, Mohenjo Daro, will be released. Quite possibly that will provoke more interest in this ancient site. And although the movie won't actually be made here, the fact that India is interested in celebrating it on film might just spark rivalry in Pakistan and inspire the authorities here to do something to conserve this vital part of their history - one which surely they should embrace or at the very least, protect.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and Thursdays at 11:02 GMT

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published27 June 2012